BY Mackenzie Lad & Erika Morris

Monday afternoons are a busy time for James Barrington.

As the community chef at The Depot Community Food Centre, Barrington and a handful of volunteers have just three hours to prepare over 200 meals for Tuesday’s meal service.

For many of the diners (that the Centre refers to as “clients”), it’s not just a meal, it’s a break from the circumstances that brought them through the doors in the first place.

And, and Barrington says, “The food tastes great too.”

Around 1 p.m. volunteers trickle in, don aprons, and take up their stations in the kitchen. The truck delivering the weekly food donations from Moisson Montreal, Montreal’s central food bank, has come and gone, and the kitchen is stocked up with fresh produce and pantry staples.

Margaret Cameron, a volunteer of three years, grabs a cutting board and greets the familiar faces in the kitchen.

“After so many years, you would think that chopping vegetables would get a little bit tired, but it’s a real community,” she says.

Volunteers in the Depot Community Food Centre work hard to prepare meals for their clients. Photo by Erika Morris.

Usually Barrington is tasked with creating the daily menu from scratch based on whatever ingredients are delivered. But on this day the kitchen has a special guest—a community member who has come to share a recipe from her own cultural cuisine.

On the menu today: Algerian lentil stew, with a side of roasted cauliflower and radish salad.

The Depot has served low income residents of Montreal’s Côte-des-Neiges – Notre-Dame-de-Grâce borough for over three decades, providing more than 20 social programs and bringing the community together, quite literally, around a table.

It’s not your average food bank, in fact, it’s not a traditional food bank at all. The Depot is Quebec’s first Community Food Center, part of a network of Canadian non-profits working to tackle the structural causes of food insecurity from within communities across the country.

The Depot Community Food Centre prepares meals for those in need. Photo by Erika Morris.

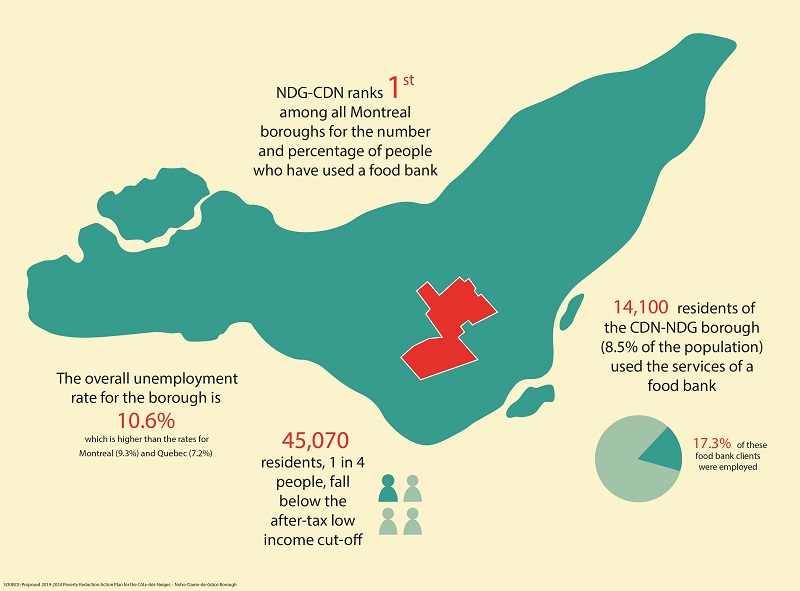

In Montreal, the CDN-NDG borough has the highest number of residents regularly using emergency food services. In 2017, that number rose to 14,100 according to the Roundtable for Poverty Reduction CDN-NDG.

Barrington has worked as the community chef at The Depot for over two years now. His chief responsibility is preparing and coordinating the meal program, which runs alongside the emergency food basket program twice a week.

“The raison-d’être of the meal program is to provide sort of new and exciting ways of using what comes in the emergency food baskets,” says Barrington. “I think we do a good job of showing people new things they can do with ingredients that they receive.”

The meal service is often the first point of contact for The Depot’s clients, and from there they’re introduced to a variety of other programs, ranging from cultural cooking classes, community gardening, to advocacy and social justice services seeking to address issues such as housing, employment, and civil engagement.

It means that the Depot’s clients don’t have to navigate the maze of government and community assistance programs on their own.

With traditional food banks we see the problem of wealth inequality being solved in a way that doesn’t necessarily work for communities,” says Barrignton. “This space doesn’t fit into that box. We serve fresh, healthy meals within our community and many people come to eat those meals, enjoy themselves, and be active in their community.”

Some facts on food insecurity in NDG. Infographic by Mackenzie Lad.

Over the years Barrington has seen a significant increase in the number of clients using the services. “We were serving between one and 200 people, maybe a little more than that from time to time. Now, we tend to serve between 200 to 300,” says Barrington.

“Definitely things are getting worse,” says Kim Fox, The Depot’s director of programming. “Food insecurity really is due to lack of income, so it’s an inadequate wage problem. Our minimum wage is nowhere near being able to cover the cost of living, and the cost of living is rising, and therefore people who are working one, two, three jobs are still struggling to put food on the table,” says Fox. The meal basket program, which offers clients a take-home basket full of staple foods and fresh produce up to twice a month, has also seen the number of participants double says Fox.

For many, buying fresh produce is expensive. Photo by Erika Morris.

Joel Coppieters, a minister at Cote Des Neiges Presbyterian Church, sat on the Roundtable for Poverty Reduction CDN-NDG which found that a quarter of CDN-NDG residents, over 45,000 people, live below the poverty line in 2017. But even before he saw the numbers, Coppieters was well aware of the effect on many of the community members attending his church services.

“Every Sunday morning after the service we serve a full lunch, and we found that for some of the refugee families who come, that’s one of their biggest meals in the week,” he says. “So we tried to figure out where the holes were. And as we did that, we realized there’s always people that fall between the cracks.”

Income, immigration status, and housing are three big pieces of the poverty puzzle, according to Coppieters. Immigrants and non-permanent residents make up half the CDN-NDG population, many of whom lack the required paperwork to gain access to government assistance services.

Cote-Des-Neiges Presbyterian Church offers a free lunch every Sunday to those in need. Video by Erika Morris.

At The Depot, more than half of the people who receive emergency food baskets are immigrants or refugees.

“As you start addressing the systemic issue, you start bumping your head up against the government regulations,” says Coppieters. “Whether it’s accessing housing or food, there’s about four levels of government that are involved, and you got to get them all to work together.”

Coppieters recalls that the recommendations from the Rountable’s 2019 report were limited in scope by the incoming municipal administration’s push for short-term, initiatives that could be completed within 24 months.

“To their credit, they’re working at it, and as of December of 2019 the borough of CDN-NDG adopted Plan d’Action Sociale, which basically takes the work of the roundtable and tries to lay out a critical path, an action plan of how we apply some of these things,” he said.

But Coppieters calls it “low hanging fruit.”

Fox sees a similar pattern of government spending across the board. “A lot of government funding is going towards traditional food bank models and providing emergency services, rather than tackling the issue with a long term plan,” says Fox. “Giving out food to people really isn’t tackling food insecurity, it’s a much bigger issue.”

Though seemingly insurmountable at the outset, the community food center model sets a new precedent for meaningful action towards long-term solutions to food insecurity. And for community members that use the services, it makes all the difference.

As an organization we need to fight the broader system on behalf of the people that come to us,” says Fox. “It’s doing education work, spreading the word, and doing it from the voice of the community.

Back at The Depot, the Tuesday morning meal service draws a crowd of familiar faces. A group of men greet each other with hugs and handshakes and take up seats at their favourite table by the window.

After receiving a warm plate of food from the kitchen staff, a new client quietly wanders around the restaurant-style dining room, looking for a place to sit. Within minutes she’s eating and laughing with a new acquaintance.

“We’re trying to change people’s perceptions of what emergency food looks like,” says Fox. “It’s all about building these networks, starting with the main ingredient, which is food.”