BY Simona Rosenfield

In 2019, the Quebec National Assembly saw more than 100,000 Quebecers sign a petition asking the government to provide medical coverage for vitamin C doses as a cancer treatment. This practice is already made available to patients in Ontario, leading many Quebecers to spend their own money to travel across the provincial border for treatment.

Two months later, the government responded.

No.

“Democracy is imperfect and sometimes messy,” says Liberal MNA David Birnbaum. “Thus [a petition] is one other cog in our democratic processes.”

Petitions have a reputation for their slow nature and their infrequent results. Historically, they were not the first choice for activists looking for change. Since they often accompany other forms of political action, it’s not clear how effective petitions have been.

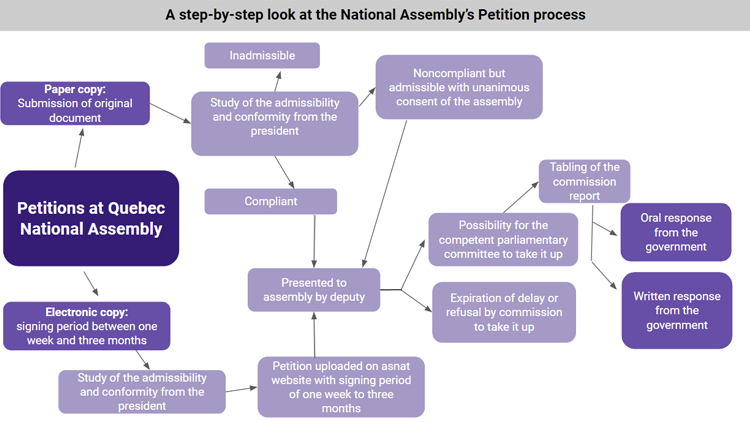

A flow chart of the petition process. Media by Simona Rosenfield.

Some local activists still find petitions useful.

“They’re only effective if they’re part of a broad communications strategy,” says Laurent Levesque, president of Chantier de l’économie sociale. “[Petitions are] generally not very effective in and of themselves.”

Laurent Levesque is a co-founder of cycling advocacy group Montréal à Vélo and Utile, a nonprofit that develops affordable student housing. Photo courtesy of Laurent Levesque.

More recently, Quebecers turned to a petition to ask the government to exempt the homeless from its Covid-19 curfew. The petition amassed more than 20,000 signatures.

Between the COVID-19 outbreaks in shelters and the fines from police, the curfew proved “not only unjust but also a health hazard,” according to Donald Tremblay, founder and director general of the Mobile Legal Clinic, the organization that filed the initial petition.

Following the death of homeless man Raphaël André, “The government was intransient,” Tremblay says. “The Premier didn’t move.”

The Mobile Legal Clinic didn’t wait for the petition process to make its way through the Assembly. They took the matter to the courts, and a superior court judge ruled in their favour before the petition was even tabled.

Petitions can serve another function besides creating change within government. They’re used to spread awareness, to develop networks, and to promote civil society organizations according to Daniel Beland, director of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada. He says petitions can help community organizations develop a following and help them mobilize more effectively in the future.

Even if a petition does get sponsored by an MNA and accumulates strong public support, it certainly doesn’t guarantee reform.

“It doesn’t have a terribly good track record of success,” says Ethan Cox, a political commentator in Quebec. “The government typically is in the business of ignoring people unless they feel forced to do otherwise.”

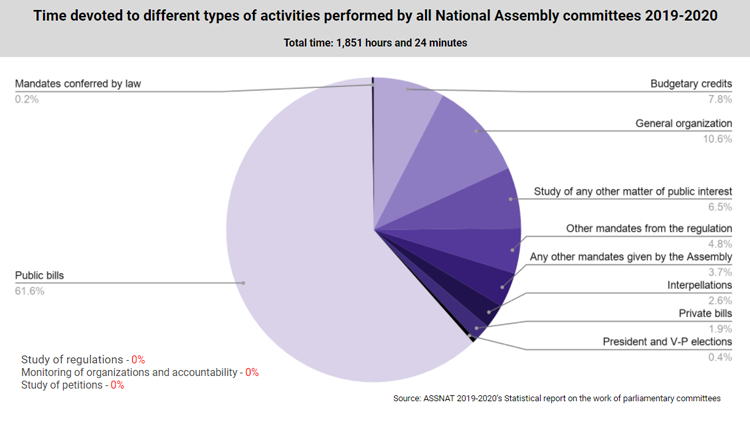

Pie chart of the floor time spent in the National Assembly between 2019-2020. Simona Rosenfield.

“It’s simple: never under the CAQ have citizens been invited to be heard following a petition submitted to the National Assembly,” says Quebec Solidaire MNA, Christine Labrie in a Facebook post. “Every time, the CAQ sends someone to explain to us that we don’t need this [petition] and that they are already doing it en masse.”

Petitions that pass through the National Assembly have to meet certain requirements and pass certain checkpoints, making them ineffective conduits for political pressure, especially when the party in power is able to drag its feet on the clerical steps. This renders time-sensitive petitions futile, and extinguishes any measure of pressure with administrative setbacks serving as a convenient alibi.

“Citizens have very few levers to exert power, to exert pressure on politicians,” Cox says. “The pressure that matters on politicians comes through the media.”

So, what gets media attention? “You may have to resort to protest to really indeed call the government to action,” Levesque says, having organized many protests through his work as founder of Montreal Velo and Utile, two Montreal-based community organizations. “Typically it shows a higher level of engagement in the community.”

Social action that takes more effort, or higher levels of engagement, implies greater public distress and is therefore more likely to prompt a response from the government. Unlike protest, Levesque considers signing a petition a social act with a lower level of engagement.

Crowds assemble around the base of Mount Royal at the end of the Montreal Climate March, on April 27, 2019. Photo by Daniel Stephen Horen Greenford.

Some believe social movements are instrumental in stoking public debate. Social movements work “to change the way we think about problems,” says Pascale Dufour, specialist in social movements and collective action.

Levesque has seen success firsthand when protesting.

“Especially protests that seize the imagination,” he continues. “I’ve found that they can be quite effective.”

A petition’s effectiveness also comes down to who is in office and who supports it. A petition will have more success if the voter base of the party in power initiates or supports the cause.

Infographic of various factors that influence a petition. Simona Rosenfield.

For example, according to Beland with the CAQ in power, a petition signed predominantly by those living in Montreal, anglophones, or minorities, will be less likely to influence change than one supported by their voter base — francophones living in the regions.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, policies pass much faster, sometimes within a week or even days, in order to meet the demands posed by the crisis. Normally it could take years of studying a policy before implementing it. While this change is felt by the public directly, avenues for communicating feedback, such as petitions, operate at their regular, slow pace.

“In this situation with the CAQ and with the pandemic, we’re really in a restrictive democracy,” Dufour says. “It’s very difficult for social movements to be heard and that’s a problem.”

Even before the pandemic, petitions moved too slowly to constructively respond to policies at the speed at which they passed in government. Now, it’s even worse. “Because things move so fast, I think obviously social media is probably the best way to get your message heard,” Beland says. The challenge to reach the government has been amplified by a reluctance to protest because of COVID-19, further limiting safe options.

MNA Birnbaum insists that the government is here to listen to the people, noting some alternatives to petitions that may get the government’s attention.

“There are letters to be written to elected officials,” Birnbaum says. “Social media, with all of its dangers and advantages, affords all kinds of access to delivering your own message.”

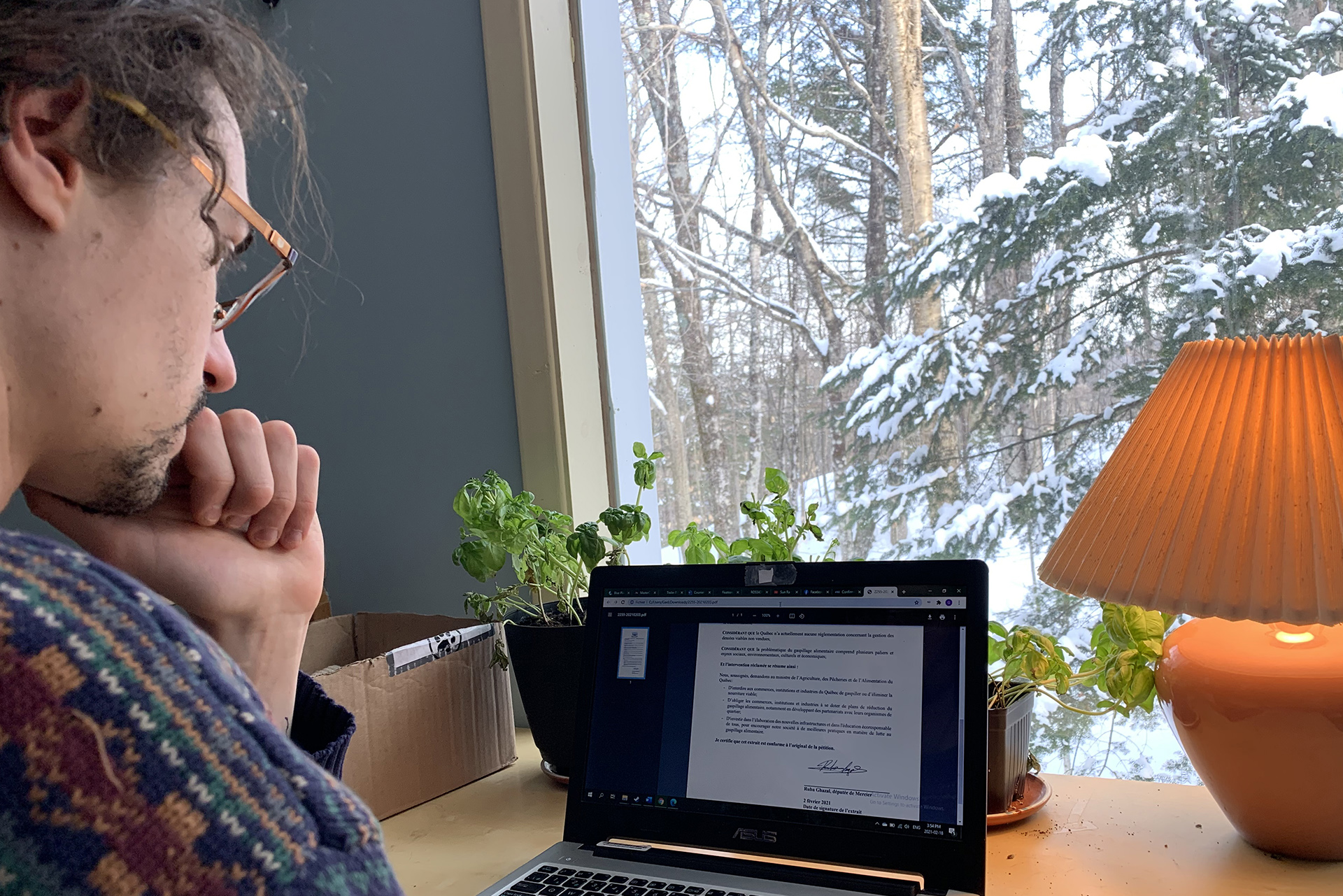

Trois-Rivieres-based activist signs a petition submitted to the Quebec National Assembly. Photo by Simona Rosenfield.

But critics say the issue is greater than simple access to government officials. “This isn’t a communication problem,” Cox says.

With the debate over viable petitions going unfilmed in parliament, the decision making process is largely unavailable to the public, a CAQ government distinction that concerns MNA Labrie. “It is clear that the democratic machine is broken,” she writes on Facebook. “[We urgently need] parliamentary reform and a reform of the voting system.”

Watchdogs are calling for greater public involvement in the political process, especially as quick policies become increasingly more invasive in people’s everyday life.

Cox sees many avenues for political change.

“Organize your friends, your neighbours, your family, your community,” he says. “Put pressure on the government through the media, through social media,” Cox concludes. “Use every avenue available to you.”

Despite its ultimate failure, Tremblay is happy that he filed a petition regarding the curfew.

“It’s heartwarming to see that 20,000 people took the time to send the message to the Quebec government that homeless people should be exempted from the curfew,” Tremblay says. “It just shows the humanity which drove these people to give [those] who are voiceless their voice in front of the political actors of this province.”