BY Fern Clair & Jillian Reynolds

Smartphones have become essential to our everyday lives. And with the pandemic, even more of our time is being spent by the light of a screen.

Phone addiction is not a medically accepted diagnosis as there is insufficient research on the subject. However, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.

“I feel it’s likely I have a phone addiction as all the stereotypical addiction signs are there,” says 31-year-old Kierin Kocourek, who is struggling with limiting his screen time. “I continue to cycle through social media even if it is causing my mood to worsen.”

If he is away from his smartphone and social media for too long, Kocourek has noticed he has raised anxiety levels.

A worker checks their phone during a break. Photo by Fern Clair.

“I think people don’t realize they have addictions, especially those addictions that have definitely been normalized,” says Kocoure. “It is socially acceptable to binge drink or spend hours scrolling through TikTok or Instagram. Especially throughout the pandemic, these addictions have been normalized further.”

For Kocourek, his screen time during the pandemic has increased dramatically.

“Once healthier distractions are easily available again, like the gym, movie theaters, it may be easier to avoid screen time,” said Kocourek, who has been waiting for the pandemic to be over before making an effort to drastically limit his screen time.

Student scrolls on their phone on the Montreal metro. Photo by Jillian Reynolds.

A study by Frontiers found that people’s screen time had increased drastically because of the pandemic, as it was the only way to remain emotionally connected to the rest of the world.

According to the study, “The suggestions for negative implications on (physical and) mental health warrant a strict need for inculcating healthy digital habits, especially knowing that digital technology is here to stay and grow with time.”

Lauren Myers is a developmental psychologist who focuses on cognitive and social-cognitive development. Myers says that while screen time can be a negative thing, it also has positive aspects.

“Increasingly now, people in the field are talking about even the concept of screen time being so broad that it’s practically meaningless because screen time could mean touchscreens, it could mean videos, it could mean video chatting with family,” she says.

Myers founded the Lafayette Kids Lab, a part of the Psychology Department at Lafayette College, where childhood development research is conducted, specifically on children learning from video chat.

“We do so much on screens now, we really need to talk about what we are doing on the screen to really understand how it should be used with children,” says Myers.

The Lafayette Kids Lab has found that children over the age of 16 months responded differently to pre-recorded video compared to live video. When interacting with a person on live video chat daily, children are more likely to make an emotional connection to the person and are more attentive when responding to questions.

A student scrolls on their phone at home. Photo by Jillian Reynolds.

“Obviously I do not recommend constant screen time for children, especially those younger than 16 months,” says Myers, who explains that ensuring children have a healthy relationship with screens is a must. “But I want people to see that sometimes screen time is not a negative thing.”

Myers agrees the overuse of screens and apps can be an issue, especially if people procrastinate in doing other, more beneficial activities.

“It is a tool, and if used correctly, it is another tool in parents and teachers arsenal, allowing them to engage with children on a whole other level,” says Myers.

Yet, a study done by JAMA Pediatrics in 2019 studied 2,441 children between the ages of 24 and 36 months, found there was a clear link between increased screen time and poorer performances on behavioural, cognitive and social development tests.

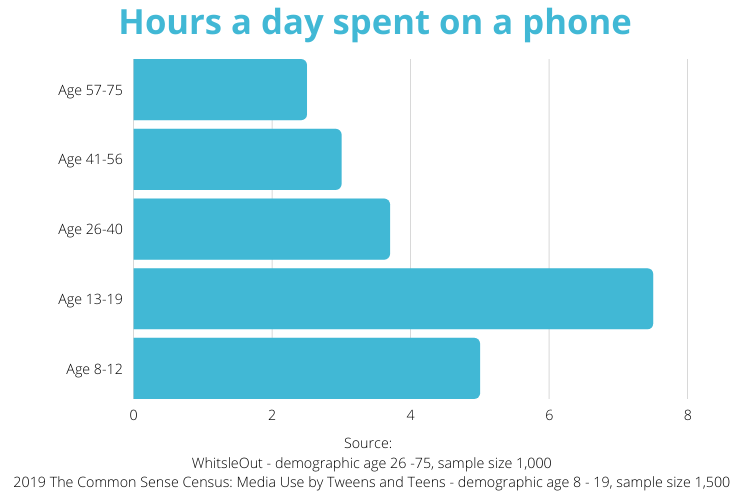

Another 2019 study by the Mayo Clinic found that teenagers 13 to 16 years old had increasingly worse mental health if they spent over three hours on social media.

Screen time drastically increases in the younger generations. Graphic by Fern Clair.

Kurtis Formosa, a 27-year-old who has been using tricks, software, and apps to limit his screen time, admits that if used right, screen time can be a productive thing.

“You could turn your phone into an ultimate object that keeps you accountable, and you can program it to do everything, but people don’t do that,” says Kurtis. “It’s the consumer that makes it a positive thing, if the right mediums were on their phones.”

Formosa started limiting his screen time around five years ago. At times he uses a black and white filter on his phone, making it less enjoyable to use.

A collection of used phones in a pawn shop. Photo by Fern Clair.

“So when you use the black and white filter for so long, like three or four months, and you turn it back on, it genuinely feels like you’re on drugs,” says Formosa.

Formosa explained that once he went for over five months with his phone on a black and white filter. When he turned it off, the vibrance of social media posts and other media gave the impression of hallucinogens. Suddenly the online realm felt surreal and fake.

Are flip phones the way to combat screen time addiction? Video by Jillian Reynolds.