BY Malo Sarazin & Ana Rubio

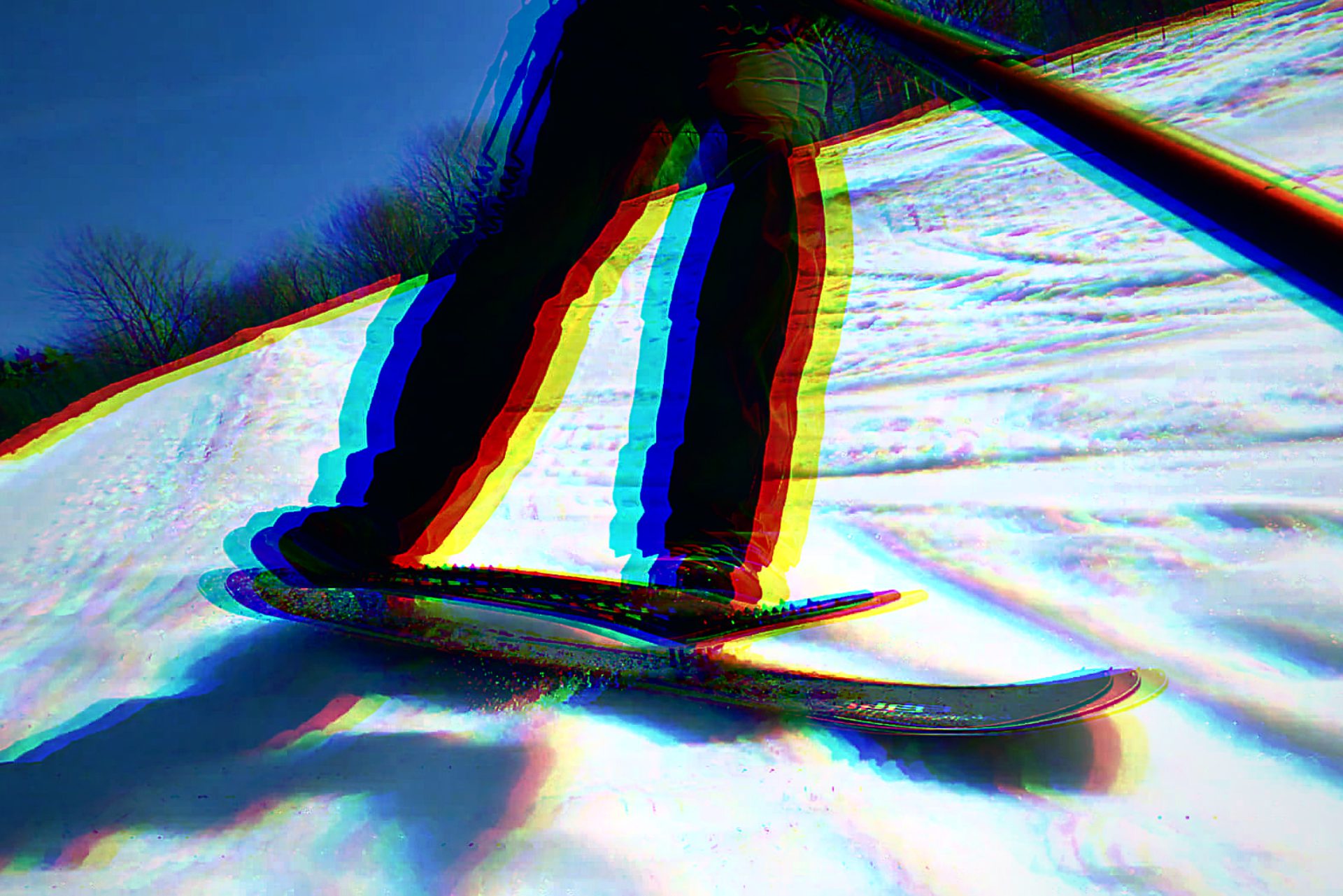

The fluorescent bottom of his skis reflects on the slushy snow. He pops on the small roller, slides down the metal rail and does a full 360 as he lands.

Philippe Gaucher has been a street skier for more than six years. The icy skiing of Quebec gets quite boring and it leaves skiers with two possibilities: Learn to ski on ice, or learn how to jump. Gaucher has chosen the latter. With his skis tied to the back of his bike, he pedals through Hochelaga on his way to a spring skiing session.

“In street [skiing], you think about almost everything other than skiing,” says Gaucher. “The main difficulty is the focus—you are constantly interacting with the urban environment and the people. I repeat song lyrics in my head to stay in the zone.”

And not without reason. He performs some difficult tricks: Sliding on three-meter high ‘rainbow rails’ and jumping off long metal stairways in the middle of Rosemont. All for the sake of the camera, or simply for the pleasure to ski.

They are now a common sight at the newly opened Dillon Ojo Snowpark located at the Montreal Olympic Stadium. The snow park, located at the bottom of the tower, opened in January 2022 and is free to access from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. every day.

The Dillon Ojo snowpark in the Olympic Stadium. Photo by Ana Rubio.

“You could just grab your board, get on the bus, get a few runs in,” says Elaine Charles, founder of the Dillon Ojo Lifeline Foundation who created the rail park, and mother of Dillon. “You don’t have to spend your whole day, you don’t have to get a lift ticket. It really was very well received by skiers.”

The park, consisting of six rails of different difficulty levels and a jump, is named after Dillon Ojo, a professional snowboarder from the South-Shore who tragically died in an accident in 2018, at 22 years old.

“[He] was just a local kid who loves snowboarding and loves his friends. And that’s what it was all about,” says Charles. And that is how most street skiers approach the sport—as a way to have fun with their friends.

Montreal is built for urban snowsports, with Mount Royal naturally creating slopes for riders to gain speed and perform tricks on rails, stairs and concrete edges, covered by the 190 to 230cm of snow the city gets each year.

Snowskater sliding down a cliff overlooking the Montreal highway. Photo courtesy of Gren Cowper.

These perfect conditions could be the reason Quebec has been a pool of talent for freestyle skiing in Canada: Twelve of the 24 athletes that represented Canada in the 2022 Beijing Olympics are from Quebec.

Having a snow park accessible by public transport on the Montreal Island was an initiative that resonated with the snowscape community.

Just like skateboarding, street skiing has a very strong DIY—do it yourself—aspect. Despite being an individual sport, street skiers form crews to help each other build snow ramps, small parks, and film and edit videos of their tricks.

At the corner of Duluth Ave. and Esplanade Ave. in Jeanne-Mance Park, skiers and snowboarders built three jumps using picnic tables and rails making a small snow park accessible to all on the slanted part of the park.

But if some crews create snow park lookalikes in city parks—other skiers prefer to do it the old school way and attempt big tricks on urban features.

“The park is basically just a re-creation of the street, it’s an artificial, safe, re-creation, but the street is the real deal,” says Ethan Jones, ski photographer and editor of Downdays, a ski magazine. “ In the street, skiers have to work with what they are given.”

It’s a double-edged sword according to Jones, because skiers have to build all of the jumps themselves. On the other hand, they also get exactly what they want.

“When you roll up to a spot and you look at it, you say: we want to hit it like this, you build it like that,” says Jones. “In the park, you roll up, and it’s the features, just the way that they’ve been built for you. It’s more of a consumer approach. Whereas Street is pure creation.”

Besides the creative process, another asset of street skiing is its accessibility. Anyone can do it, as long as they have skis and snow in their city. And in Quebec where ski passes are getting more and more expensive but snow in the streets is plenty, it is a decisive argument.

On average, a day pass to a ski hill in the Laurentians less than an hour drive from Montreal costs $65. In Avila, a hill known for its snowpark, the day pass costs $63.99 and in smaller hills like Mont-St Bruno, the 4-hour ticket costs $40.

For the skiers that can’t afford these tickets or the cost of driving up to the mountain, street skiing is a simple solution. And the snow park has made the sport even more accessible. Since it’s on a metro line, younger skiers and others that don’t own a car can now shred some rails in the heart of Montreal.

But some urban riders are still left on the sidelines: Snowskaters.

Snowskate is a growing urban sport that looks like a skateboard without wheels.

Snowskaters attempt tricks on their boards in Mount Royal park. Photo courtesy of Gren Cowper.

Snowskating is not allowed in most ski hills in Quebec, and it is forbidden at the Dillon Ojo snowpark. Skaters have to practice in the street by default or to build DIY just for themselves—which is what they did at Walter-Stewart Park near Frontenac metro station.

Montrealers have found a way to surf the city’s streets. Video by Ana Rubio.

In most public spaces around the city, street skiing, snowboarding and snow skating aren’t illegal unless they damage city property or if a complaint is made.

Verdun city councillor Sterling Downey is an avid skateboarder himself. He calls for an approach to urban planning that takes into consideration that it will be used by skateboarders, skiers and snowboarders.

“Why not think outside the box and have these spaces that have double-triple or quadruple uses,” says Downey.

Montreal has an even more ancient history with street skiing: a tow was installed on Mount-Royal in 1944. Skiers would go down the hill and end up on the campus of Université de Montreal. Skiers still ride the mountain, taking the bus up before riding down the trails filled with jumps in between the trees.

“It’s closer than the hill,” says Nikolas Manrique, a Concordia student from California who says he can’t afford to go to the ski hills every time. “After my classes, I take my skis and go for a few runs.”

Manrique memorizes the runs from his summer bike rides and uses them for skiing in the winter.

A look at the three main parks for snow skaters in the city of Montreal. Map by Malo Sarazin.

But with climate change raising temperatures every year, skiers are chasing the snow. And the city, unlike ski resorts, does not have the capacity to create artificial snow banks.

“It’s the existential threat for skiing as a whole,” says Jones.

But climate change also brings more and more unpredictable weather events, which is prompting street skiing crews to get creative. During a snowstorm in Madrid in January 2021, the Buldozze crew drove from Switzerland and took the streets of the Spanish capital to film ski segments that had never been seen before.

And that’s what it is all about, in Montreal and elsewhere: having fun where nobody skied before. And for that, urban skiers have to be creative.