BY Elyette Levy & Ketsia Nkumbu

Dwindling sales and living off his savings have been very real consequences of the COVID-19 crisis for Ronald Mason, the owner of a handcrafted pottery business in Pointe St-Charles.

And yet, they haven’t been the most difficult part of the pandemic. Being unable to interact and connect with his clients have been the biggest challenges to him as a local artisan.

“Every artist wants to see the reactions of people to their art,” he says. “It not only affects you economically, but it really affects you emotionally. You don’t see people, and that’s one of the hardest things.”

An empty pottery studio at the Maison des métiers d’art du Québec. Photo courtesy of Llamaryon for the MMAQ.

For the more than 1,100 professional artisans in Quebec—and the hundreds more who are still in training or who haven’t made careers out of their craft—2020 has been marked by financial distress and loss of clients. The intermittent closures of art shows and exhibits, along with the general population’s diminished incomes, have resulted in major drops in sales and jobs in the artisanal sector.

“Because of the pandemic, a majority of fairs were cancelled for sanitary reasons,” says Geneviève David, the communications and marketing director of the Conseil des métiers d’art du Québec (CMAQ). “And by doing so, a majority of artisans lost a lot of money. Artisans often work in alignment with these fairs in order to create the works they want to sell. They’ve purchased a lot of material, and they were faced with many expenses without having any revenue.”

Prior to the pandemic, Quebec was seeing a lot of growth in its handicrafts industry. It is defined by the creation of artistic—and often functional—objects on a nonindustrial scale using analog tools and methods. This includes the use of small-scale projects like needlepoint and beadwork, but also encompasses more complex processes like glass blowing and metallurgy.

[slide-anything id=”5251″]

In 2018, the Canadian craft sector was valued at over $2.6 billion, and accounted for more than 28,000 jobs. According to the Canadian Crafts Federation, 76 per cent of artisans’ sales from galleries, shops, and festivals came from shows and events organized by Provincial and Territorial Crafts Councils like the CMAQ.

In Quebec, 22 of these professional handicrafts events are held annually, and most of them had to suspend their activities due to COVID measures—including the two largest craft festivals in the country.

Taking place over a period of three weeks in December, the annual Salon des métiers d’art du Québec (SMAQ) in Montreal welcomed over 80, 000 visitors in 2019. On average, clients spent $180 on each purchase, for a revenue of around $12 million every year. An estimated 40 per cent of visitors purchased handcrafted goods solely from the SMAQ.

The summer edition of the event, Plein Art, is held in Québec City. In 2019, it brought in $6 million in sales every year and welcomed over 160 000 individuals, 48 per cent of whom spent between $125 and $250.

Some [craftspeople] rolled up their sleeves even more despite a precarious situation. It’s beautiful to see, and it’s also really moving because through their creations, they’ve remained resilient.”

According to Diane-Gabrielle Tremblay, a professor at the TELUQ School of Administration, a major challenge for the province’s artisans is the nature of the industry, where many professional craftspeople are small business owners or self-employed individuals and heavily rely on retail sales.

“Certain sectors have remained very affected by the pandemic, like hospitality, catering, and tourism,” says Tremblay. “For artisans, just like in the rest of the cultural sector, there isn’t always an important revenue stream. However, most people in the arts and culture industries need a second revenue, which will often be in the hospitality or catering sectors as well.”

Despite the hardships experienced by the artisan community, many remain optimistic. The CMAQ, which advocates for artisans’ interests, has noticed a promising adaptation to online commerce.

In fact, some artisanal businesses have flourished after moving to an exclusively virtual store. David recounts seeing pictures of a Kamouraska post office flooded with online orders for Arbol Cuisine, a handmade wooden kitchenware company.

“[Craftspeople] were already proactive,” says David. “And some of them rolled up their sleeves even more despite a precarious situation. It’s beautiful to see, and it’s also really moving because through their creations, they’ve remained resilient.”

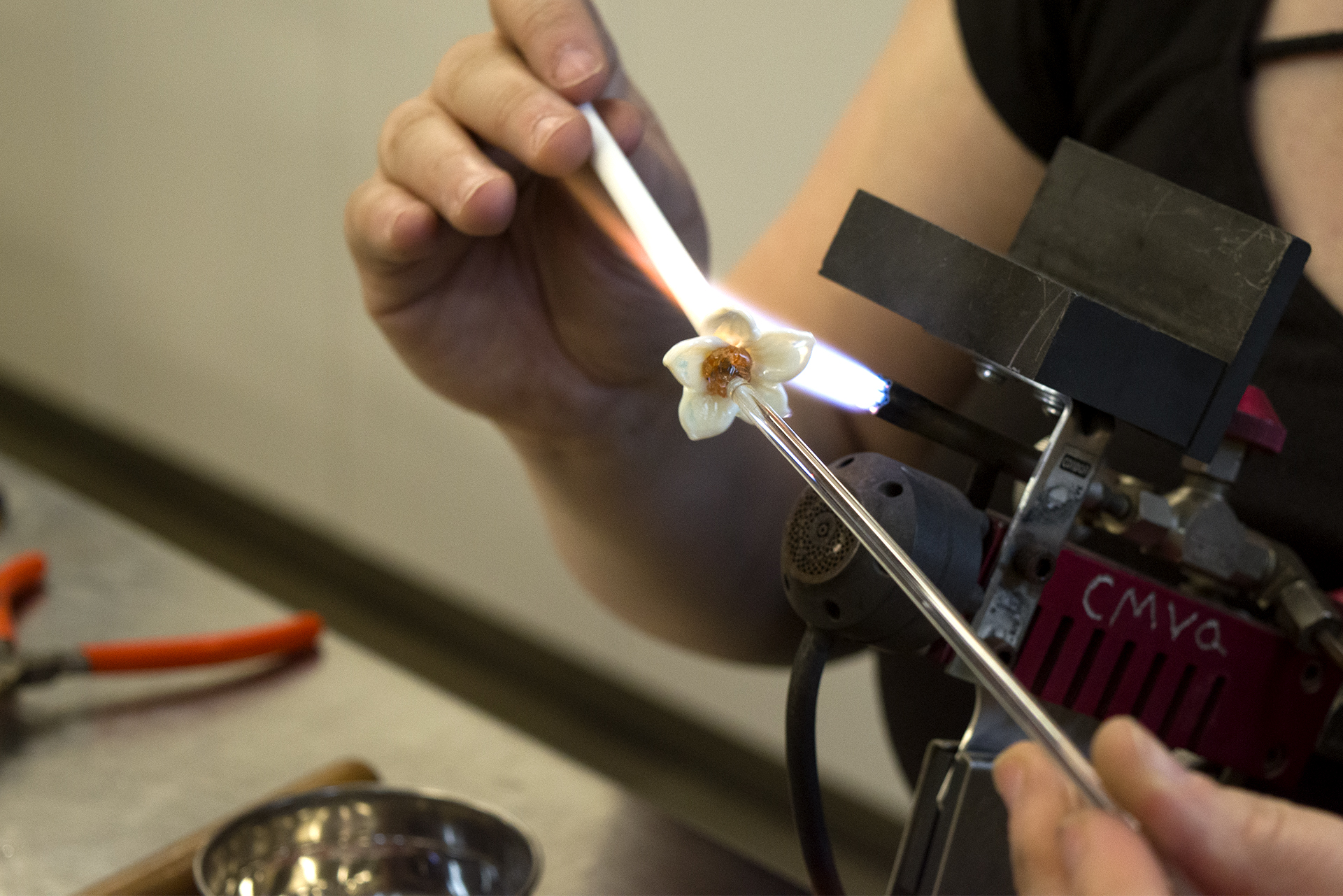

The diversity in types of handicrafts in Quebec. Media by Elyette Levy.

There is also hope for a better financial future. Just last year, Montreal’s subsidy for artists in the visual arts and craft arts was more than tripled, going from $235 000 to $735 000. Also, Quebec’s 2021 budget promised an injection of $407 million into the cultural sector.

To Tremblay, these are good signs. She predicts that, coupled with the ongoing COVID-19 vaccine rollout and the expected loosening of pandemic measures, the government will try to stimulate the population’s consumption of artisanal products. Tremblay also expects regional tourism to pick up and help other cultural markets.

“I’m relatively confident,” she says. “Artisans are closely linked to [the hospitality and tourism] sectors, so we can hope there will be an economic recovery soon.”

Professionally made glass wares are exhibited at Espace Verre. Photo by Ketsia Nkumbu.

The crafts market is also seeing a revival in other ways. Though sales have fallen, the CMAQ notes a shift in the public’s perception of handmade goods, as well as an increased interest in learning artisanal skills by younger Quebecers.

The Maison des métiers d’art de Québec (MMAQ), a multidisciplinary crafts training and education institution based in Quebec City, has noticed a growth in enrollment in the past few years, getting a record number of applications in 2019.

A major player in the MMAQ’s success since the beginning of the pandemic has been their quick digital adaptation. At the start of the first lockdown in March 2020, access to studios and the MMAQ’s facilities was completely withdrawn. So they developed videos, capsules, class forums, and more for their students and the public to learn more about various crafts.

“The pandemic has provoked changes in terms of our habits,” says Thierry Plante-Dubé, the MMAQ’s Director General. “Of course, we’re in the handicrafts industry; we’re often in contact with materials, we work in studios, we’re not very used to working on the web or with digital tools. That was something we would always postpone, we would think that in crafts, it doesn’t really apply or that it’s less necessary.”

But what started as a measure to make crafting more accessible to students became an important source of visibility for the MMAQ.

“With our recreational courses, we developed an online program in order to offer something to the greater public as well, and now, we even have people in Argentina who are also following these classes,” says Plante-Dubé.

The artisanal glass blowing industry faces uncertainty during pandemic. Video by Ketsia Nkumbu.

Ultimately, David is optimistic about seeing a new cohort of local artisans, specifically because of the cultural significance of this industry.

“[Artisans] are the pillars of Quebec, they are the pillars of who we are,” says David. “It’s a body of work we need to preserve. It’s a richness that we have here in Quebec.”

According to Mason, developing Quebec’s value of the arts is one of the most crucial ways of keeping its culture alive. Throughout the pandemic, he has noticed that although many are able to appreciate the time and care that go into his work, there is still a long way to go before society recognizes the importance of spending more on handcrafted products rather than saving money and purchasing industrially-made objects.

“We need really education and society to value locally-made things,” he says. “We do it for the art of passion. We do it because it’s a human thing to do, to create art.”