BY Evan Milner & Valerie Bayeur

Having grown up a stone’s throw from Mont-Rigaud, skiing is a luxury that Brendan Mergl knows very well.

“My parents put me on skis before I even knew how to walk,” Mergl jokes.

Brendan Mergl posing for a photo on the ski hill at Mont-Rigaud, where he learned to ski. Photo by Evan Milner.

Now, over 20 years later, it’s a sport that the 24-year-old continues to enjoy. However, he says it’s becoming increasingly inaccessible, and he points to climate change as the culprit.

“When I was younger, I’d be skiing weeks before the Christmas holidays,” he recounts. “Now I’m lucky to be on the slopes by the new year. It’s frustrating, but it’s the reality of the world we’re living in.”

The effects that climate change continues to have on the sport are less evident year-to-year, but if you consider the length and severity of Quebec winters in the early 2000s, the differences are clear.

“I haven’t noticed a huge difference in the conditions of the hills, it’s more that the seasons are shorter,” Mergl adds. “I expect to see more drastic changes in let’s say the next 20 years or so.”

The mild winters that we’ve experienced in the latter half of the 2010s are the largest threat that climate change is posing to ski resorts.

Puddles are seen flooding the streets of Saint-Lazare, Que. in the middle of February, suggesting temperatures above the freezing point. Photo by Evan Milner.

Luc Elie, owner and general manager of the Mont Rigaud ski resort about 50 kilometres west of Montreal, is experiencing the difficulties firsthand.

He says the lack of snow is not the biggest concern, it’s when the first snow falls that is the main problem. Elie says it has delayed the start of the season in recent years.

“At Mont-Rigaud, we used to have 114 days of skiing, but in recent years, we are closer to 100,” he says. “If we go back 10, 15, 20 years, that’s a 14-day difference on the season in our area.”

Elie says their goal is to be 100 per cent open for the Christmas holidays. This two-week period makes up to 18 per cent of their annual revenue.

“People are on holidays, it’s like a weekend every day,” says Elie.

Brendan Mergl coming to a stop while skiing at Mont-Rigaud. Photo by Evan Milner.

With warmer temperatures in early and mid-December, that means they must produce their own snow. Fortunately, today’s technology allows the hill to do this. However, the temperature can’t go above freezing for the snow cannons to be effective.

“Usually, we start in November to produce snow. But we don’t really have that cold weather anymore in November and December,” says Elie. “It’s very hard on the system to open, close, open, close.”

Mitchell Dickau, a researcher and contributing author of a study on the decline of outdoor skating rinks in Montreal, attributes the warmer winters to the rate at which CO2 is currently being emitted into the atmosphere.

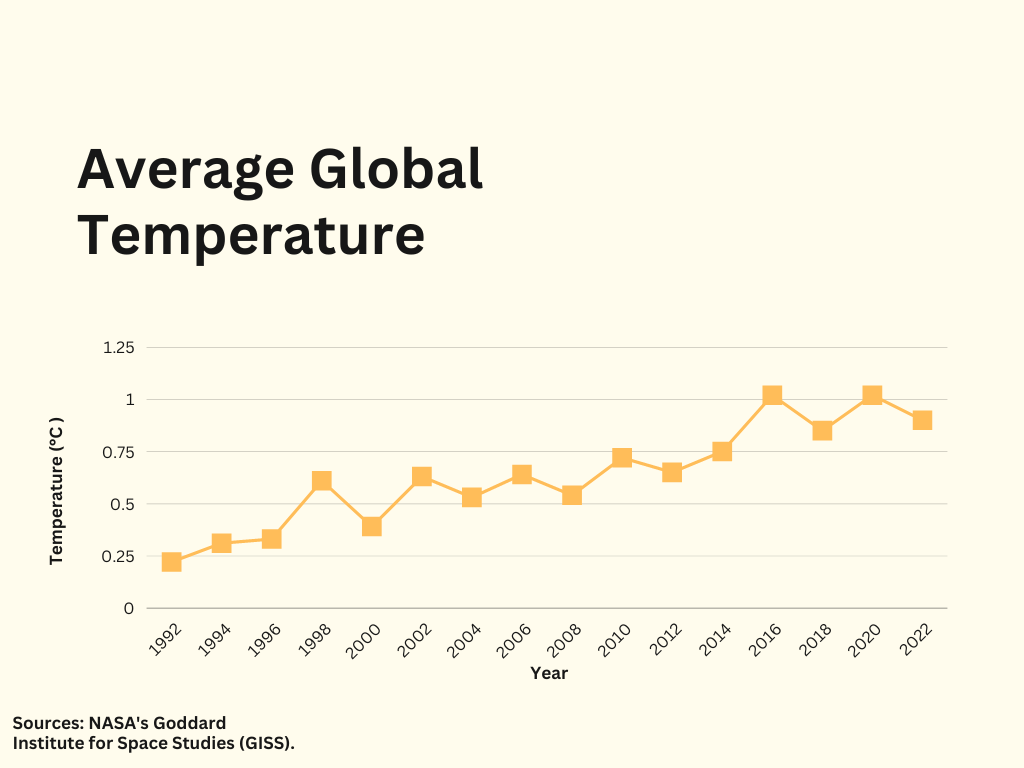

“If you take all the CO2 that we’ve emitted into the atmosphere since pre-industrial times, about 50 per cent of it has come in the last 30 years,” said Dickau. “What that means, is we’ve also seen a really fast increase in how quick our global average temperature is increasing.”

“Generally, you can just expect that every land surface on earth now is warmer than it was 150 years ago,” Dickau states.

This graph is based on findings from NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS), demonstrating the rapid rise in average global temperature in the last 30 years. Media by Evan Milner.

Over the last three years, Elie has invested $1 million in snowmaking equipment to combat the mild temperatures. The investment includes doubling the capacity of their pipes, and purchasing new cannons that can produce snow efficiently.

“When we have a window of cold weather, we have to produce the maximum that we can,” he says. “We produce more in little time. The idea is to have eight inches to a foot base [of snow] on our hills, that way when we work with the machinery, the skiers turning and all that, we don’t catch the ground,” says Elie.

At the end of 2022, they used the snowmaking machinery for 450 hours and even that barely cut it.

“We were seeing it melt every day, but we were looking long-term, the cold weather was coming back and there is snow up ahead, so we said we’ll be patient and we’ve been lucky with January with all the snow we got.”

Dickau says in order to stop global warming, we need to bring our emissions of CO2 to zero.

“It’s not a matter of halving our emissions or reducing them, they actually need to reach zero. Otherwise, temperature is still going to increase – and that’s the minimum requirement.”

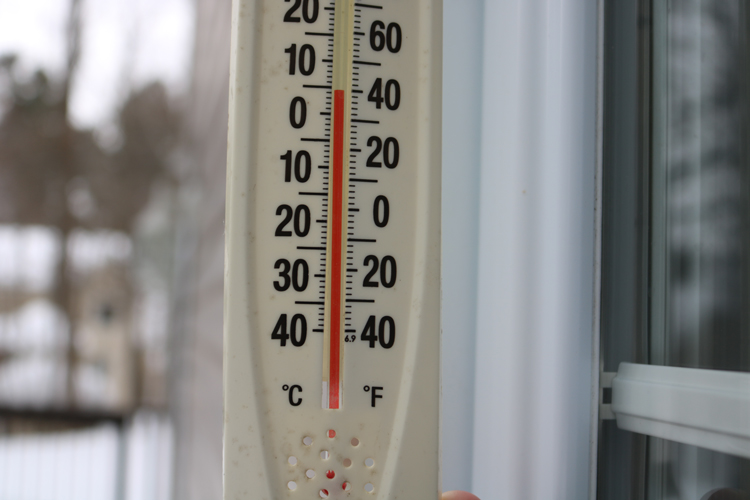

A thermometer showing 4 C on an early February morning, well above the average temperature for that time of day at that time of year. Photo by Evan Milner.

The sustainability of the ski industry in the future depends on the path we take, says Dickau.

“It’s completely up to us how much more warming occurs,” he says. “What I can say for sure, what climate change will affect in the ski industry, is you will have a shorter season. So, it will start later and end earlier, that’s for certain.”

However, he doesn’t fear for the future of skiing as a whole. While temperatures might be milder, they will remain cold enough for ski centres to continue operating. Instead, he says the variability in weather caused by climate change is more concerning.

“If we look at outdoor skating as an example, if you have a rink that’s frozen and is in good condition, and then you have one or two days above zero, you have to do a lot of work to make that rink skateable again,” said Dickau. “It’s the same for ski hills.”

The outdoor rinks in Montreal this winter are very disappointing. Video by Valerie Bayeur.

Ski Canada estimates that the ski industry produces nearly $1.4 billion of revenue annually. Quebec, alone, is responsible for $295 million, they say.

Elie says he hasn’t noticed a drop in the traffic that comes through Mont Rigaud, but says that people are pickier with the weather now more than ever.

“If it’s nice out, people are there. If it’s not nice out, the place will be empty,” says Elie. “The weather affects the clientele directly.”

To adapt to the shorter seasons, Elie has looked elsewhere for ways to profit in the off-season. In 2011, they started building a cross-country mountain biking trail, which he says has thrived in the last four years.

Other activities include hiking and obstacle courses, but the main source of income lies in the hands of the ski season.

“The revenues are nothing compared to the winter,” he said.

With the change in average global temperature, Elie feels it’s time the government helps with the financial costs of operating a ski resort.

“In the touristic areas, we need grants that can help us with the equipment,” he said. “It’s unbelievable how expensive it is.”

In 2022, the government of Quebec granted Mont-Rigaud financial aid as part of the PARIT: Programme d’aide à la relance de l’industrie touristique (Assistance program to relaunch the tourism industry).

Quebec’s Minister of Economy, Pierre Fitzgibbon says the government “probably has a role to play in allowing all the ski resorts, not just one, to modernise. Otherwise, it’s an activity that could be in danger.”

Elie mentioned the price of lift tickets barely makes up for his cost of operations.

“People find they’re expensive for this sport, but with everything that it costs to operate a ski hill, it’s like our ski tickets are not high enough, because the costs of everything around is so high.”