BY David Sami & Anna Justen

Raphael Kerwin had to shut down the Blue Dog Motel bar on Saint-Laurent Boulevard several times due to pandemic measures. It was during one of those shutdowns that he received a notice of complaint from the Office Québécois de la Langue Française (OQLF).

“When I got that letter, I was a bit ticked off,” Kerwin says. “We’re not even operating and we’re not allowed to operate as a business. It’s during a pandemic and you’re nitpicking about small issues like my social media pages.”

The notice stated that the content of his business’ Facebook page, as well as its name, was all in English and that it should be changed so as to include French.

Since both Kerwin’s and his wife’s native tongue is English, most of the content on their social media accounts are in English. Photo by Anna Justen.

This wasn’t Kerwin’s first altercation with the OQLF, of course. Back in 2014, they had sent him a notice to add a French descriptor in the window of his bar, given the English business name, unaware that there already had one that read “Bar/Barbier”.

In compliance with the OQLF’s regulations, Kerwin has a French descriptor on the window of his business. Photo by Anna Justen.

OQLF spokesperson Chantal Bouchard says the bar’s English-only posts on social media websites violates the Charter of the French Language (CFL) which states that the commercial publications of a company must be in French. Posts can also be in other languages if the company wishes, provided the French requirement has been achieved.

“As a reminder, the OQLF is not imposing a fine,” she adds. “It is the courts that could do so, should companies refuse to comply.”

The OQLF building on Sherbrooke Street in Montreal, QC. Photo by Anna Justen.

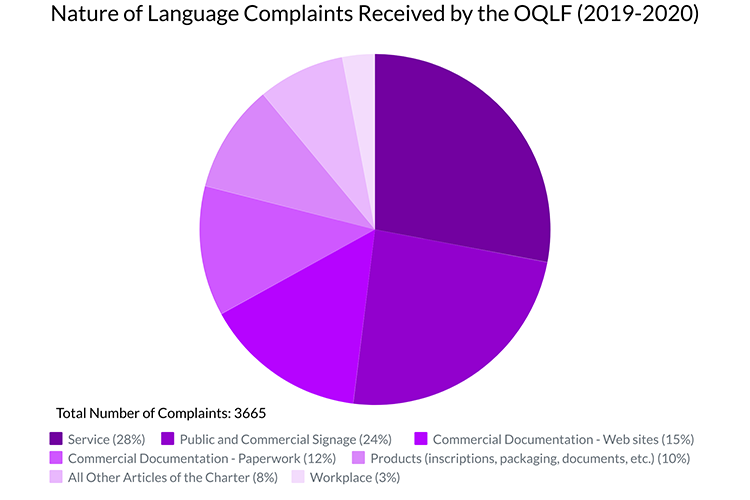

Complaints regarding online material accounted for less than a fifth of all the complaints to the OQLF in 2019 and 2020. The biggest cause of complaints was the language of service, amounting to over a quarter of the total.

Pie chart regarding the nature of language complaints received by the OQLF between 2019 and 2020. Pie chart by David Sami.

Kerwin replied to the OQLF, saying that he wuldn’t approach the subject while still dealing with Covid-19 restrictions. Regardless, he does plan on making changes when everything’s settled.

“We will definitely be writing all of our posts in French and in English from now on,” he says. “That’s not hard for us to do. We have no problem with doing that at all. My main issue is that the government is spending money on attacking ridiculous things like this rather than promoting the French culture.”

A look into whether the Office de La Langue Française’s campaign “Partage ton Français” is going to boost the use of the French language in the province. Video by Anna Justen.

According to lawyer Julius Grey, an expert in constitutional law, the OQLF has the jurisdiction to control what businesses post online.

“In Quebec, it is a general consensus that French is obligatory,” he says. He notes that commercial signage should include French, but it can include other languages.

The Blue Dog isn’t the first business to run foul of the language charter. In 2016, 11 anglophone businesses were given notices by the OQLF that their websites, among other things, were in violation due to them being exclusively in English. These businesses went to court to plead their case, saying that Art. 52 doesn’t explicitly mention online material, but their plea was unsuccessful.

The Quebec Court of Appeal argued that point, saying that there’s no reason to differentiate commercial material, whether it be posted online or printed on a brochure.

Grey points out that the OQLF is getting new powers, courtesy of the CAQ government’s Bill 96, that was created for the purpose of promoting and strengthening the French language.

“They allow the OQLF, various parts of the language bureaucracy, to go in anywhere, look into people’s computers, to obtain or make people give information, all without recourse to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms (CRF), because it has the notwithstanding clause,” Grey says.

“What will happen if they adopt Bill 96,” Grey adds, “is that the police investigating a murder will not have the sort of powers that the OQLF has when investigating the use of English somewhere. It’s very distressing.”

Grey argues that more needs to be done to get through to francophones.

“I’ll give you an example: I wrote an article about this issue in The Gazette, and I couldn’t get it printed in French, even though I had originally written it in French.”

At the end of the day, Kerwin is still planning on riding out the storm that is COVID-19 before considering action of any kind. While he does say that his business reflects the clientele he receives, moving forward, he plans to do his best to uphold the OQLF’s standards.

Kerwin sits alone at his bar. Since he is not allowed to operate his business, he barely stops by anymore. Photo by David Sami.