BY Olivier Du Ruisseau & Bianca Mercuri

The Villeray boutique of Veux-tu une bière may be very narrow, but it is filled with bottles from floor to ceiling, making the most of its charmingly messy space. Frédéric Quintal, a regular customer of the chain of Quebec craft beer and wine retailers, was pleased to notice a bottle of Les Bacchantes, his favorite local producer.

“Quebec wines have gotten so much better these last few years,” he says, as he exits the store with two bottles in his hands, satisfied.

Quintal grew up near Dunham, in the Eastern Townships, the birthplace of Quebec wine. He says he has always been aware of the industry’s potential. “But now, it seems that all of Quebec has finally seen the light,” he says with a smile.

While they had an unenviable reputation a couple of decades ago, Quebec wines and spirits have become increasingly popular in the province, especially since the pandemic. Some pandemic measures might even have helped local alcohol businesses.

“I think that is because shopping locally was encouraged more than ever,” says Patrice Lavoie, the founder and manager of the island’s three Veux-tu une bière stores. “Because it became tedious to go to the SAQ; and because people wanted to treat themselves in a difficult period… We have been lucky.”

The Veux-tu une bière store chain has been selling Quebec wine since 2018. In 2021, wine represented 8 per cent of their total sales, according to Patrice Lavoie. Above, a wine shelf from their Villeray store. Photo by Olivier Du Ruisseau.

Louis-Philippe Mercier, the founder and co-owner of La Boîte à Vins, a two-store chain that specializes in Quebec wine, says his revenues have increased by 1300 per cent since the pandemic and that he was able to hire a record 16 employees.

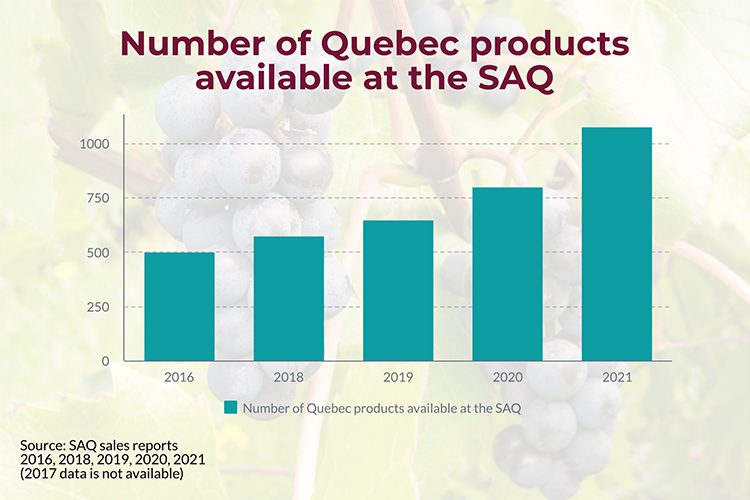

Even the SAQ, which still holds a monopoly on the in-store sales of imported wines and of all spirits, has seen a 27 per cent rise in sales of Quebec products in the last year only, according to its 2021 annual report. The chain has also welcomed more than 250 new local products in their stores this year, out of 1078 in total.

The number of Quebec products available in SAQ stores across the province has increased steadily in recent years. Infographic by Olivier Du Ruisseau.

“A great wave of love for Quebec wine and spirits that was already present before the pandemic has only accelerated because of it,” says Linda Bouchard, a spokesperson for the SAQ.

Annick Van Campenhout, the secretary-general of the Quebec Union of Microdistilleries (UQMD), also believes that Quebec spirits have also been able to grab a good share of the market.

“The first good gins arrived in Quebec in about 2017, and then the rest followed so quickly that our union now totals about 270 products of all kinds,” she says.

Van Campenhout believes this movement has positively impacted independent businesses. Local distilleries are the only locations allowed to sell spirits outside the SAQ, and she notes that they have increased their on-location sales since the pandemic hit.

The experts behind the face of the local alcohol community speak on a societal shift to supporting local businesses. Video by Bianca Mercuri.

Frederic Laurin, an economist and wine market specialist says the phenomenon was predictable.

“Just look at what happened to the Quebec microbrewery market in the last 20 years… The interest in locally-produced food and gastronomy in Quebec has been growing for quite some time,” he says.

Laurin believes it took longer for the province’s wine to gain the same popularity as local beer mostly because wine was only allowed to be sold outside of the SAQ in 2018.

Sommelier Louis-Philippe Mercier is part of the Quebec Wine Council (CVQ). He agrees that making wines available outside the SAQ has been a key to their success.

“Since winemakers and agencies put pressure on the government to be able to sell more locally and to offer a greater diversity of products, a very promising new market opened its doors,” he says.

His store, la Boîte à Vins, has become the largest retailer (in terms of sales and number of available wines) of Quebec wine in Montreal.

“I immediately jumped in,” Mercier says.

La Boîte à Vins prides itself in selling rare wines that aren’t offered at the SAQ. Mercier advocates for a complementary relationship between specialized grocers and the state society. For Laurin, the increasing demand for such a model also explains the change of the law in 2018.

Van Campenhout strongly deplores the fact that local producers of spirits are not entitled to the same privileges as wine producers. She says that it is partly thanks to the popularization of “spiritourism” in the province that sales on-location have risen.

Cirka Distillery in Montreal, open since 2014, hosts tours of its facilities year-round, and sells spirits on site, in an effort to diversify its revenue sources and connect with its clientele. Photo by Bianca Mercuri.

Other local businesses have benefited from an even more recent measure towards the liberalization of the alcohol market in Quebec.

Indeed, amid the first wave of the pandemic, the provincial government allowed restaurants and bars to sell beer, cider and wine for take-out. As they could pair this new possibility with offering more Quebec wines, some businesses managed to keep their heads above the water.

“About 75 per cent of the sales of our online store, which we opened only when our dining room was closed during the pandemic, were of Quebec wine,” says Catherine Goupil, coordinator at Pullman, one of Montreal’s oldest wine bars that has a large selection of Quebec products. “We did it to survive, and it worked,” she says.

Nikolas Da Fonseca, cofounder of more recent Montreal wine bar Vinvinvin, also says that his customers are increasingly interested in Quebec wines and can sell more every year. He, too, says he was only able to survive the last two years because he could sell alcohol for take-out.

The wine bar Vinvinvin, in Rosemont, has been selling wine for take-out since the beginning of the pandemic, and continues to do so, despite the gradual reopening of its dining room. Photo by Olivier Du Ruisseau.

Local producers, however, are facing a number of challenges on the horizon.

For instance, following a complaint by Australia to the World Trade Organization in 2018, Canada was forced to sign a potentially game-changing agreement last year. Quebec wines did not have to pay a markup to the SAQ to be sold outside of its network, but that is expected to change, possibly within the next year.

“We’re very anxious to see to what extent the government may be going to compensate the producers, because it could increase the retail price outside of the SAQ, and therefore, hurt the market,” says Laurin.

Van Campenhoot says that the microdistillery market, on the other hand, feels that spirits must be able to be sold outside the SAQ, because they are entirely dependent on the financial health of the network.

For just over three weeks between Nov. and Dec. 2021, SAQ warehouse employees were on strike, which reduced the amount of products that could reach the shelves. Above is a photo of the empty shelves of an SAQ store in the Mile End on December 31, 2021. Photo by Olivier Du Ruiseau.

“With the last strike at the SAQ, since some of our products could not be sold because they were stuck in the warehouses, I tell you, some of our members may have to close their doors,” says Van Campenhoot.

That is why the Quebec Association for spirits to go (Association pour spiritueux à emporter du Québec, ASPQ) was created last year.

“At least I see that if the market is evolving so much, moving so much, it’s really because there’s a strong excitement about the products and new businesses,” says Laurin.