BY Zachary Cook

As a young boy, Rex Holwell recalls freshwater ponds and sea-ice in Nain being four to five feet thick by December. Years later, these same ponds and sea ice are freezing much later in the season, making conditions unsafe for travel.

“Once the sea ice forms, it is our highway,” says Holwell, SmartICE Regional Operation Lead for Nunatsiavut. “People rely on travelling to go hunting, fishing and get wood to keep their houses warm.”

Ducks in Botwood Harbour. Due to changing weather conditions, many wild-life are migrating later in the season. Photo by Zachary Cook.

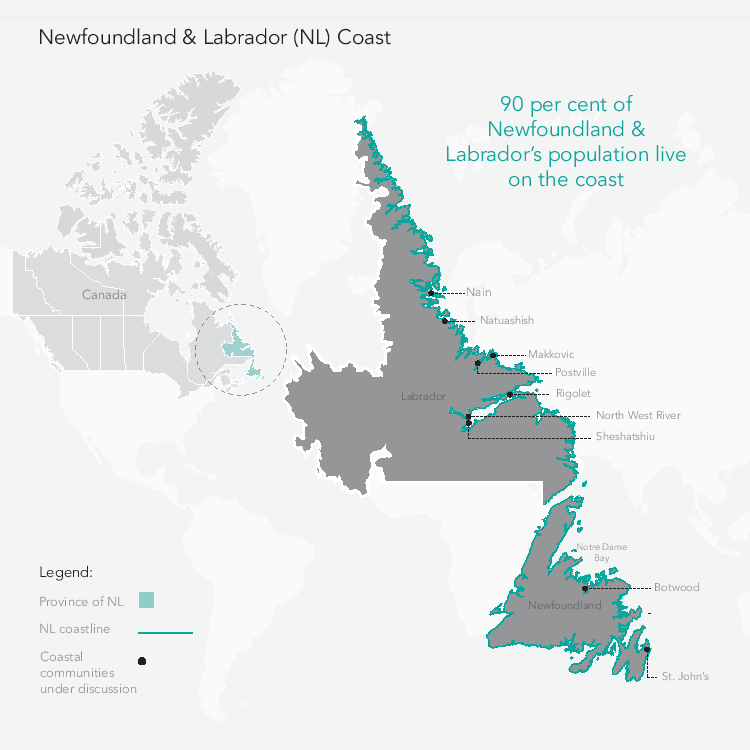

Rising average daily temperatures, changes in ice and intensified storm conditions continue to affect Newfoundland, particularly in Northern Indigenous communities in Labrador.

“We’re seeing the impacts on both sides in the salt and freshwater, so it leads to much longer routes on rough terrains along the sea. Or people just don’t do it,” says Holwell.

Coastal communities in Newfoundland and Labrador. Media by Zachary Cook.

According to Holwell, communities across the coast of Labrador are experiencing similar conditions. “Makkovik has zero ice so they see it, I see, everybody here in Labrador, we’ve been seeing it for a long time.”

Thinner ice makes travelling to remote areas unsafe. It disrupts travel to Traditional gathering locations and affects the shipment of essential products and services to communities.

“I know a few people are taking trips to those places; they’re either taking the longer route inland, which may take 6 hours,“ says Holwell. “Because they don’t have that highway, they’re taking twice or triple the amount of time to get to their Traditional hunting or fishing grounds.”

Sea-ice Monitoring and Real-Time Information for Coastal Environments (SmartICE) is a social enterprise, founded by Dr. Trevor Bell that provides ice monitoring technologies and equipment to Northern Labrador and Arctic communities for local use.

“It helps keep everybody safe using expertise and Traditional Knowledge they’ve been taught through their parents, grand-parents and friends,” says Holwell.

SmartICE Operator taking the SmartQAMUTIK for a trip to gather sea ice data.” Photo courtesy of Michael Schmidt.

SmartICE started with three initial sites in St. John’s, Nain and Pond Inlet. Since then, it has expanded across Canada, to 22 sites.

The enterprise trains operators in communities and accommodates to individual community’s requests. “We’ll meet with the community and listen,” says Holwell. “We consult with Hunting and Trapping Associations (HTA) and Hamlets.”

“We get input from the Elders and the youth that attend these meetings; they’ll tell us what they want, and how we can help them,” says Holwell.

Holwell is also the Northern Productions Lead and trains local Inuit youth through SmartICE’s Employment Readiness and Technology Production Program at the Northern Production Centre in Nain. “I give them resume, cover letter and interviewing skills,” says Holwell. “At the end of the five week course, I will actually teach them how to build a SmartBUOY. That’s something they can’t wait to come in and learn how to build.”

Youth assembling a SmartBUOY at the Northern Production Centre in Nain, Nunatsiavut. SmartBUOYs are stationary sensors deployed in the ice to collect data. Photo courtesy.

The SmartBUOYs are assembled and tested in Nain; they then get shipped to St. John’s, NL and deployed where orders need to be fulfilled. Holwell’s duties as Regional Operations Lead include deploying and maintaining the SmartBUOYs; weekly trips to frequently traveled locations around Nain and training operators in other communities.

Due to ice conditions, Holwell has only completed one trip this year.

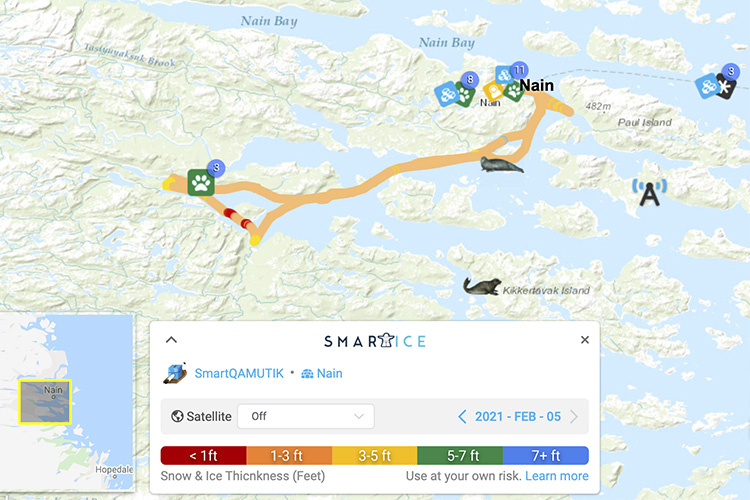

Holwell and other SmartICE operators recognize that not everybody has access to a laptop, tablet or smartphone.

“I screenshot my run and print it off; I’ll post it in the local community hotspots, you know at the post office, down at the local Northern store, where I know people are interested in seeing it, and of course social media – I post it on the Nain bulletin board,” says Holwell.

SmartICE SmartQAMUTIK run, posted to SIKU.org on Feb. 5, 2021. SIKU.org is an Indigenous social network created by and for Inuit for ice safety, weather, hunting stories, language preservation and knowledge transfer. Screenshot.

SmartICE is just one of several Indigenous focused responses to climate change.

The Indigenous Leadership Initiative is a non-political, Indigenous-led organization dedicated to fostering Indigenous cultural responsibility to land, guiding future generations and working with governments to secure funding for Indigenous protected and conserved areas.

In 2017, the Government of Canada invested $25 million dedicated to the Indigenous Guardians Pilot Program. In 2018, the pilot was taken on by Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Three governance bodies have since been established, giving Inuit, Métis and First Nations partners an individual opportunity to decide how they want the program delivered. “The first year we funded 28 proposals; 24 of which were First Nations, three Inuit and one Métis proposal,” says Julie Boucher, Spokesperson for the Indigenous Guardians Pilot Program.

The program provides employment and professional training to Indigenous peoples across Canada who monitor, conserve and protect the land, water and wild-life. “The program’s current focus is on understanding how to use the data collected by Guardians and to collaborate with other biologists and scientists,” says Jack Penashue, Superintendent of the Innu Nation in Sheshatshiu, Labrador.

Along with biology research, data collection and online filing, Guardians work in the field, on the land. “Right now we have 15 individuals that work under the Guardian program in the Sheshatshiu area,” says Penashue.

In 2020, $600,000 was announced to fund 10 new projects under the Indigenous Guardian Program. By May 2021, the final ten First Nations proposals will be announced, indicating the end of funding within the pilot.

The program is currently at the evaluation stage, assessing the effectiveness of programs on an individual basis.

By Fall 2021, an overall evaluation of the pilot will be complete and serve as the base of a business case requesting long-term funding for Indigenous Guardians across Canada. “I definitely see a future for the program.” says Boucher. “If you look at protected and concerned areas and Indigenous Peoples tend to have a higher percentage of success when it comes to recovery and restoration of species at risk.”

In 2019, the Land Needs Guardian campaign was created, calling for long-term investments in Guardian programs and Indigenous-led stewardship. In just one year, 50,000 people have joined.

To sign the Land Needs Guardians campaign, click here.