BY Abby Yaeger & John Ngala

Despite winning racial profiling and excessive force cases against police officers, Pradel Content says harassment from police has only gotten worse.

“I cannot even step out of my house. Ever since I made this complaint, every month I get harassed,” Content says. “My life is hell right now, and I need people to be accountable for what is going on.”

Content walking his dog near his home in Laval. Photo by John Ngala.

“Do you know how it feels to see officers notice that it’s you walking your dog, then creep along beside you?” Content says. “But if you can’t prove it, you might as well not talk about it.”

Content, a Black anglophone man living in Laval, has spent years in court defending complaints he has filed with the help of the Center for Research-Action on Race Relations (CRARR). The most recent complaint he filed concerns a recorded interaction with Laval police in July 2018. When Content started recording the interaction that took place outside of his home, two officers asked if he had a problem with his phone. Content said he was protecting his rights, and one of the officers in the cruiser laughed.

As the officers began to leave, Content said, “bitch,” and was issued a $77 dollar ticket a week later for insulting the officers. Content contested the ticket and Justice Chantal Paré of Laval Municipal Court acquitted Content in 2019. The Quebec Human Rights and Youth Rights Commission ruled in Content’s favor, asking for a total of $24,000 in damages from the City of Laval and the two police officers involved.

Years before, Content also filed a complaint against Montreal police after he was wrongfully detained and subjected to excessive force outside of Atwater metro station in March 2014. He was stopped based on a vague suspect description of a Black man wearing black clothes. Despite being disabled and using a cane, Content was shoved against the hood of the police car and handcuffed.

In 2019, five years after the incident, the commission awarded Content $15,000 in damages. Content says he has yet to see any of that money, and if he does, it will go towards legal fees.

Content says he doesn’t leave his house more than a few times a month due to his disability but is still regularly stopped by police. Photo by John Ngala.

Content says friends in Laval warned him not to file a complaint. “They told me, ‘Are you crazy? You made a report? Your life’s going to be hell. They’re going to harass you, they’re going to give you tickets left and right.” Despite the warnings, Content says he filed the complaint because he felt he needed to protect his rights.

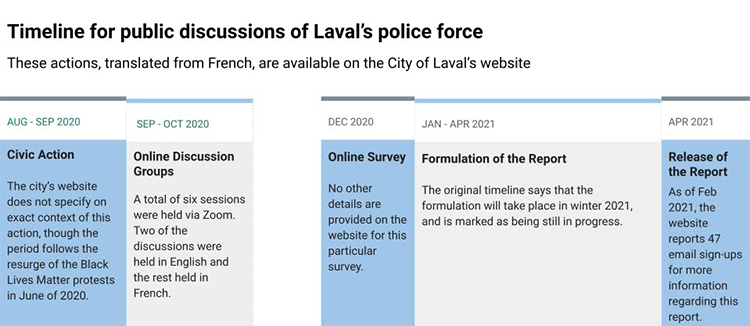

In 2020, Laval released a report that outlines ten measures to be taken towards improving relations between Laval Police and the public. The measures include a data collection system on police interactions and a call to implement body cameras.

The document says the city’s first goal is to establish a “better understanding of the ethnocultural diversity” in Laval and to diversify the recruitment and hiring process of the Laval Police. The measures include public consultations on police services, which took place as online group discussions last fall. The results of these consultations are set to be released in April.

The Laval police are said to release a report with measures to better understand ethnocultural diversity this spring. Media by Abby Yaeger.

Virginie Dufresne-Lemire, a lawyer who specializes in cases of police brutality and abuses of authority, says that measures like data collection could help to determine cases of racial profiling, but it’s important to recognize the limitations of data collection.

“We really need to look at how they are going to gather that data. What information gets collected and who decides? We need to have a critics perspective on how it’s going to be done,” she says. “But data is important. It can help us to evaluate the behavior of the police officers differently.”

Dufresne-Lemire explains that the most accessible option to file a complaint against police in Quebec is with the Quebec Police Ethics Committee. The filing doesn’t cost money and doesn’t require a lawyer.

In reality, she says the process isn’t so simple.

“Anyone can file a complaint, but rare are the cases that go through the whole process,” Dufresne-Lemire says. “I strongly suggest that people be accompanied by a lawyer, but a lot of people can’t afford one, so they’re alone. And it’s hard to make your point in an institution where the power is not equal.”

The SPVM released its action plan to combat racial profiling in July 2020. The report vows to prohibit “any police checks that are unfounded, random or based on a discriminatory criterion,” and to “better establish the context of police checks and identify the disparities of police checks of members of ethnocultural, known as ‘racialized’ or belonging to a visible minority or Indigenous community.” The report also makes a commitment to analyze data regarding street checks.

The SPVM action plan begins with a signed message from Sylvain Caron, the director of the SPVM. The Laval action plan was released by the city of Laval, but isn’t signed by any member of the Laval police.

These responses were conducted after a June 2020 report by the Office de Consultation Publique de Montreal (OCPM) which proposed thirty-eight recommendations for combatting social and racial profiling in Montreal, “a phenomenon that has been largely documented for many years,” according to the report.

Racial profiling is not unique to Laval; it’s prevalent on the island of Montreal as well. Video by John Ngala.

Content says throughout his court cases, the videos he’s taken of his interactions with police have been his strongest evidence. “Every piece of proof that I have in winning my case is from my own videos.”

Police cruiser outside of a Laval police station. Photo by John Ngala.

While Content says he’s glad to have won his civil rights cases, he doesn’t feel enough has been done to fight the root of the problems he deals with in his day-to-day life. “I’m so glad I won because it means that I won, but it’s just because I have the footage to prove it.”