BY Katherine Vehar & Sarah Jesmer

Vanessa LaPrise has been using food banks for the last four years, and it keeps her and her son afloat, she says. She’s used the food programs at Montreal’s Old Brewery Mission, Sun Youth and Chez Doris.

“Being hungry is being hungry,” says LaPrise, a mother who says she feels “blessed” to have access to these resources.

“If it weren’t for the food banks, I don’t know if I’d be able to survive,” says LaPrise. “When COVID happened so many people wanted to help out, it saved me.”

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Montreal had the highest rates of food insecurity of any major Canadian city. Compared to January 2020 an additional 163,000 Quebecers are unemployed, according to Stats Canada. Food prices have increased, with the cost of vegetables up 6.5 per cent and meat 9.13 per cent. These factors have contributed to rising rates of food insecurity throughout the city.

“Food insecurity is when you don’t have enough money to buy your food,” says Rotem Ayalon, a social development advisor at Centraide and member of Montreal’s Food Policy Council.

“Your monthly budget has to first go to your rent and your bills. And when you don’t have much left for groceries, you become food insecure,” says Ayalon.

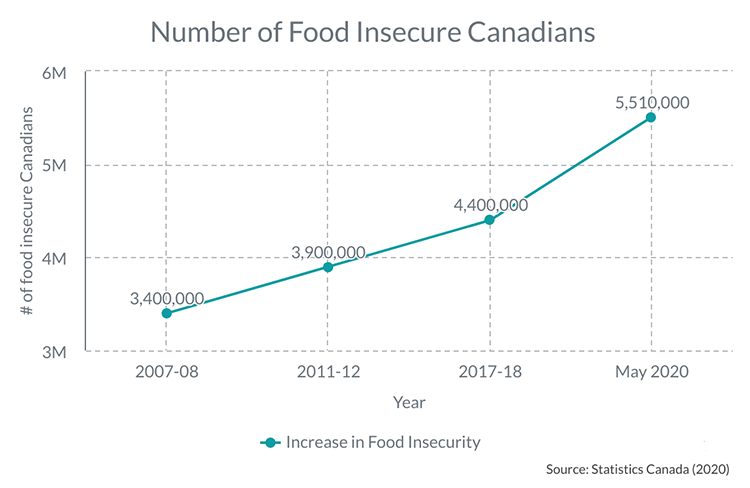

A report released by Statistics Canada indicates that rates of food insecurity rose by 39 per cent in the first week of May 2020. Researchers note that the study is conservative and likely underestimates the total increase, but the surge is undeniable.

In May 2020, one in seven Canadians indicated being food insecure. Media by Katherine Vehar.

In June 2020, Moisson Montreal reported that it had distributed 40 per cent more food than the year before. Moisson Montreal – the largest food bank in Canada—has not slowed down since, according to the Montreal Food Policy Council. It reports that community organizations have seen 40 to 60 per cent rise in demand for their services.

“The demand is increasing, there are new people who are asking for help,” says Maria-José Raposo, director at the Centre D’Aide à la Famille, a nonprofit that supports families and victims of domestic abuse.

Raposo says they had to switch their main mission to be a food bank for the duration of the pandemic because of the restrictions that health measures have put on gathering and community.

“People who used to be secured financially are now in a situation where it gets harder and harder every month to pay their bills and to feed their kids,” she says.

[slide-anything id=”4445″]

The numbers tell a similar story. Centraide estimates that 28 per cent of adults in the greater Montreal region had difficulties getting food during the lockdown.

Dimitri Espérance, co-founder of collectif la DAL in Saint-Henri, says that with social distancing and lockdown measures, the closure of many restaurants, and the burden of commuting during the winter, the situation for Montrealers living in food deserts has only gotten worse.

However, COVID-19 has not only affected those seeking food. It has also affected organizations who provide resources.

“It really changed the way we do things,” says Raposo. “We have to have less volunteers because of space [and] we have new costs. We need to have boxes or bags, trucks, and people as well.”

A volunteer helps unload a truck of donated food items which will be distributed to locals in need. Photo by Sarah Jesmer.

Homeless shelters have also experienced a steep learning curve. They’ve had to stop providing certain services in the hopes of limiting the spread of the virus in their facilities.

Unlike most of the organizations who have been adapting to an increase in demand for their services, the Old Brewery Mission has been unable to accommodate their usual patrons.

Catherine Vachon, head of food services at the Mission explains how the pandemic forced them to limit their services and cut back on the amount of people they help.

“For now, we’re concentrating our efforts on vaccinating as many people as possible,” says Vachon, who hopes that by doing so they can start accepting walk-ins again.

The Mission is no longer accepting walk-ins and is only feeding hot meals to patrons in their dorm residences. Photo by Katherine Vehar.

Nonetheless, for many homeless Montrealers, lack of access to shelters and warm meals has proven to be perilous at times. Local restaurants have been helping address this need by donating food to organizations like the Mission. “We’ve been getting entire contents of freezers from restaurants that have just shut down,” says Vachon.

Restaurants have also joined forces with community initiatives and are donating dozens of hot, takeaway meals to those in need. Concerned citizens Jessica Glazer and her partner Randy Belham have been feeding homeless Montrealers at Place Émilie-Gameline since October of last year. They have partnered with local grocers, bakeries and restaurants, who donate food that the pair distribute.

“If you’re going somewhere to get free food, you’re hungry,” says Glazer.

Community members are stepping in to fill gaps being created between homeless Montrealers and the resources they used to be able to rely on. Video by Sarah Jesmer.

“Food insecurity is the popular word right now,” says Espérance, “but we prefer to talk about food justice.”

Collectif la DAL, which aims to serve Saint-Henri’s west end, doesn’t pass out food boxes – they’ve set their sights on a longer term solution to a problem they say they’ve seen in their community for decades. They want to convert an old St. Henri fire station into a co-op grocery store and a temporary summer farmers market.

Espérance says although they’ve rallied hundreds of signatures of public support, they’re facing red tape and zoning regulations that have stalled the campaign. But they’re not giving up the fight.

“Food banks were created as a solution to a crisis,” he says, “but they are not a durable solution to food, which is a right.”

Espérance co-created la DAL after he noticed long lines outside a food bank near his house. Photo by: Sarah Jesmer.

With community organizations having to comply with public health guidelines and adapt to an increase in demand, there have been inevitable casualties in the services they can provide. With emphasis placed on limiting the potential spread of the virus, things like community kitchens and shared public spaces closed. Priority was shifted to home deliveries and food boxes.

“Food is generally a way to bring people together,” says Ayalon. Community organizations often use food as a means of inviting people to the table to discuss larger issues, like mental health or security concerns. This is most often done through communal spaces, like gardens or collective kitchens. “The pandemic has just made it even more difficult to reach the people who are already isolated,” says Ayalon.

The pandemic further emphasizes the fact that food insecurity is not an issue that exists in a vacuum, and its solutions are not limited to putting food into hungry bellies. Rather, food insecurity tends to be the result of greater social problems.

LaPrise says that the COVID-19 mutual aid resources that were made available to her did more than just feed her and her son.

“It really made a big difference in my life,” says LaPrise. “I was struggling, and I felt like the whole world was in it with me. I wasn’t the only one anymore.”