BY Sarah Jesmer & Enya Leger

Twenty-two-year-old Hannah Gold-Apel goes to the pharmacy for fun. She strolls through the aisles up to four times a week.

“I’m just walking through like, ‘Oh, these are things I haven’t even thought about incorporating into my beauty routine, I guess I should probably add these things,’” she says. “And then they’re of course prohibitively expensive and marketed in such a way that I don’t actually need them but I start to feel like I do.”

Gold-Apel sees a difference in the quality and number of products marketed to men versus women, but also in the price.

“The prices are just legitimately different. The quality is also different,” she says.

Women who buy hygiene or products marketed to women have likely noted an extra charge at the register that has become known as the “pink tax.”

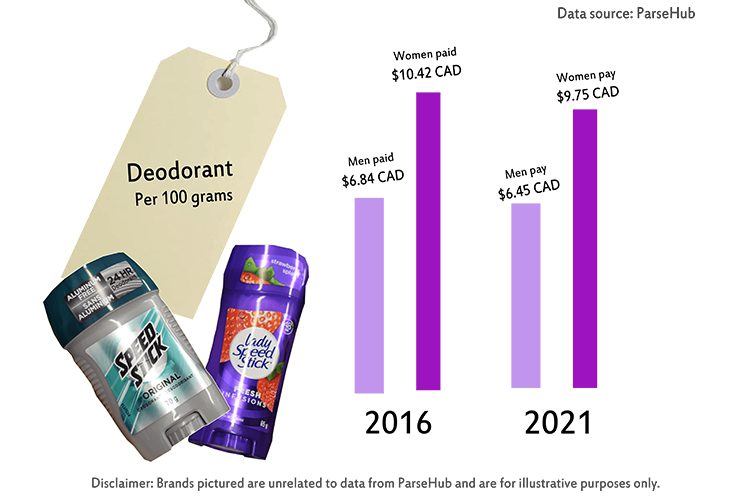

In 2016, data-scraping company ParseHub said it analyzed prices of 3,191 personal care products. They found that women pay 43% more for their hygiene products when compared to prices for items marketed to men.

ParseHub revisited their study in February 2021 and found that not only has the pink tax persisted, but its total average cost for women has gotten larger. They compiled prices from thousands of products and reported the gap in prices to be more than 50 per cent. They do not specify the exact percentage.

ParseHub looked at products from companies like Walmart and Shoppers Drug Mart. By their count, 100 grams of deodorant marketed to women cost on average $9.75 in 2021. But 100 grams of deodorant marketed to men cost $6.45. That’s a 34% difference for 2021 deodorant. They also found that razors marketed to women cost 4.99% more and body wash cost 65.71% more.

Slideshow: According to data-mining company ParseHub, the pink tax still exists in 2021. All brands pictured have no relation to data from ParseHub and are for illustrative purposes only. Infographics by Sarah Jesmer.

Slideshow: According to data-mining company ParseHub, the pink tax still exists in 2021. All brands pictured have no relation to data from ParseHub and are for illustrative purposes only. Infographics by Sarah Jesmer.

Slideshow: According to data-mining company ParseHub, the pink tax still exists in 2021. All brands pictured have no relation to data from ParseHub and are for illustrative purposes only. Infographics by Sarah Jesmer.

Slideshow: According to data-mining company ParseHub, the pink tax still exists in 2021. All brands pictured have no relation to data from ParseHub and are for illustrative purposes only. Infographics by Sarah Jesmer.

Slideshow: The Golf des Moulins entrance building abandoned in Terrebonne. The golf course was sold in 2018 because of financial problems and has been inaccessible to the public since. Photos by Bryanna Frankel.

These differences add up. In 1994, a California state committee found that services and products marketed to women cost them a total of $1,351 US annually.

Gold-Apel said campaigning against the pink tax is not high on her priority list because of the enormity of the changes required.

“I feel like there hasn’t been a lot of momentum in the activist sphere in terms of the pink tax,” she says. “Mostly I think because feminism has moved on to a much more intersectional approach and I think that like even the nomenclature of the Pink Tax might really tie it to some stereotypical ideas of femininity and some stereotypical ideas of gender that just like don’t serve young activists anymore in the way that they used to.”

A Montrealer tried to fight this tax in court in 2016. Aviva Maxwell wanted to know if gender-based differences were allowed under the law.

“It just shows that there’s certain things systematically in our society that we just sort of gloss over, [that] we don’t actually think about, ,” says Maxwell, an 33-year-old artist and entrepreneur. “There’s repercussions how it actually affects people and we just tend to take the excuses of retailers or corporate messaging to heart.”

In early 2017, Maxwell and her lawyer, Michael Simkin, asked the courts to approve a class action lawsuit against gender-discriminatory pricing. The suit targeted corporate giants including Unilever, Walmart, Shoppers Drug Mart, Jean-Coutu, Loblaws, Metro, Familiprix and Uniprix. The Coalition of Consumer Associations of Quebec joined the lawsuit as a plaintiff.

“I wasn’t really expecting anything to come from it, because I know the law system or the justice system to be quite slow. So I didn’t think that there would be much attention to

It,” said Maxwell. But it did.

A few months later in December 2017, the Office de la protection du consommateur in Quebec published a review of “Pink Tax” legislation around the world. The study pointed to Canada’s 1982 Constitution and Quebec’s Charter of Rights.

“It is fair to say that the laws adopted so far are not sufficient to curb the phenomenon of the ‘pink tax’. Despite numerous debates, the existing laws do not target products, provide for exceptions and low fines with little dissuasive effect. It is difficult to identify practices that Quebec could adopt as is for the time being, with the exception of prevention and awareness measures,” according to the report.

In other words, to slash the “Pink Tax” in Quebec, it would have to be done by politicians changing the law, not through a lawsuit.

Aviva Maxwell, center, and three of her four children in 2017. Maxwell said she was glad her kids could see her pursue this lawsuit because, she said, it showed them they could stick up for themselves when they think something is unfair. Photo provided by Maxwell, taken by her son Phoenyx Britton.

The class action lawsuit was quietly dropped in 2019.

“We were authorized to withdraw from the class action,” says lawyer Maryse LaPointe in an email, who worked on the class action on behalf of the plaintiffs. “Indeed, we were of the opinion that unfortunately, Quebec’s law did not offer any protection against the pink tax. It is more a file of political pressure than an issue for the court.”

Maxwell says there were two reasons behind dropping the case. She says she couldn’t keep up with the attention the lawsuit required due to family issues. She also says the lawsuit got her a seat at the table to negotiate about pink tax pricing.

For example, she says she and other plaintiffs met with Unilever-owned Dove Canada.

“I felt quite satisfied at the end of the day, because there really was a strong effort being made now to, sort of, sensitize themselves and educate themselves,” said Maxwell. “Now, obviously, it’s a corporation, or it’s a business. So we can’t necessarily take everything they do, let’s say, at face value. They’re still going to try to make profit as much as they can. But I do feel like there’s sensitization there.”

She says she also met with Walmart, Loblaws, and “other small pharmacies.” Dove Canada, Unilever Canada and Unilever USA, Walmart and Loblaws did not respond to requests for comment.

“They also sort of sat down at the table. And we had a couple of days of just intense meetings and conversations,” she says.

The motion to dismiss was filed in Quebec’s Superior Court under Judge Chantal Corriveau. Without a law that says allegedly discriminatory pricing was illegal in Quebec, Corriveau wrote, the action wasn’t expected to go in Maxwell’s favour: “…The steps taken by the Applicant have enabled it to find that that the facts alleged do not allow, or will hardly allow, the conclusions sought […] the Applicant’s appeal is probably doomed…”

Although the pink tax has survived these legal battles, some consumers are taking the issue into their own hands.

Liz Singh says the answer to gendered price differences is not substitution between two choices, it’s reevaluating whether one really needs to buy these products at all. Photo by Sarah Jesmer.

Liz Singh, a street work coordinator with the local non-profit Head and Hands, gets around the Tax by simply not buying what’s being sold.

“I think the pink tax is something I think about a lot,” she says. “I think of it as just one kind of small facet of beauty culture and the way that it costs.”

Singh says the pink tax is an irritation she doesn’t need.

“I don’t end up doing a lot of beauty stuff because it costs a lot of money. So I opt out of most of it. I haven’t cut my hair in forever,” she says. “And it took me ages to find a hairdresser in the city who wasn’t charging $100 just because I was a woman.”

She sometimes makes her own products, like deodorant using baking soda and oil. “It’s not necessarily cost saving sometimes. It’s definitely not time saving, but I like to take every opportunity I can to just not participate in this whole situation,” says Singh.

It’s a situation that requires deep investment, she says, of more than just money. For Singh, time spent working to afford and perform beauty regimens using pink taxed products is time that can be used elsewhere. She believes lasting change stems from moving past simply substituting a product choice from a “woman’s” item to a “man’s” version.

“Yes, we can shift the norm and shift the marker over time. No, it’s not a reason to settle for the way things have always been, says Singh. “We should be working towards a space where we’re not spending as much energy as we are reinforcing this binary in the first place.”

Montreal’s BLOME Salon is tackling inequality in the prices of beauty services, through standardized pricing. Video by Enya Leger.

The fight to address economic access to women’s hygiene items like menstrual products continues. Sophia Heath is the co-president of Monthly Dignity, a Montreal-based non-profit that works to eradicate local “period poverty” – the economic burden of buying menstrual products.

Non-profit Monthly Dignity distributes menstrual products for free to places like local shelters and schools. Photo submitted by Sophia Heath.

“We always use this kind of model of toilet paper, and how toilet paper is free just about anywhere you go anywhere in the world,” says Heath. “But the reality is menstrual hygiene products are kind of the same thing and yet they’re taxed as if they’re luxury, which is just infuriating to me.”

Heath says Month Dignity works to alleviate those costs associated with menstruation, which works out to around $2,000 USD annually, according to a 2015 study by Mic that adjusted the 1994 California estimates for inflation. Canada did cut the federal tax on some menstruation products in 2015, following a series of protests and petitioning.

Campaigns against period poverty and the pink tax address the same underlying issue of unregulated discrimination, she says, and not just in Montreal.

“For me personally, the thing that really drives me is that I can see tangible change. And in my lifetime, I have noticed a difference. And even just in the conversations that I have with the people around me, sometimes there are general, like, actual opinions are being changed,” says Heath.

Maxwell says she can see greater engagement with the pink tax issue, even if her shopping trips to the pharmacy haven’t changed much since 2017.

“It’s important to keep asking and interrogating the status quo,” says Maxwell. “Because we are a consumer-based economy, and we have to have the power now, we have to ask the questions.”