BY Victor Tardif

Isabella Michaud is a tenant in Montreal’s Saint-Henri borough. She grew up there and lived twenty-eight years in the same apartment. But for almost three years she’s been pressured to leave by her new landlord.

“They do everything so that I leave,” she says.

Three of her neighbours have already left.

“The three on the right, they successfully made them leave with money,” she says, noting that she didn’t accept money to leave.

Assisting her throughout the process is Inès Benessaiah, organizer for the Projet d’Organisation Populaire, d’Information et de Regroupement (POPIR), a south-west tenant rights group.

“She resists but is subjected to a lot of verbal intimidation. He continuously pressures her to sign an agreement for her to leave,” says Benessaiah.

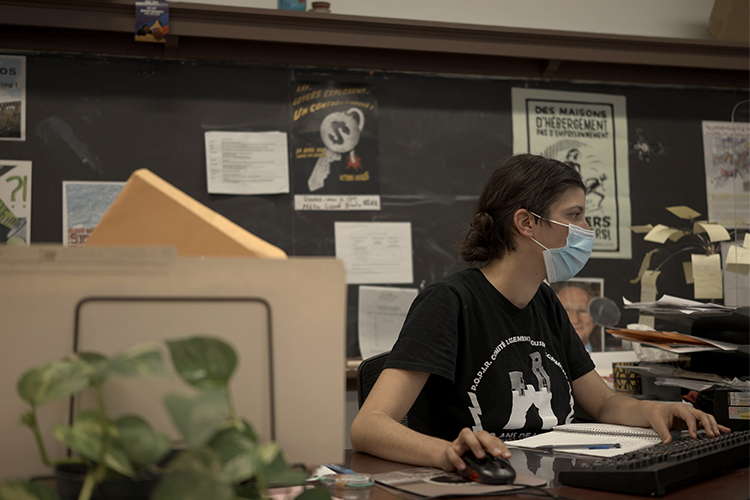

Inès Benessaiah is responsible for the Saint Henri and Ville-Émard areas for the Projet d’organisation populaire, d’information et de regroupement housing committee (POPIR).

Ménard says the dispute has put her in danger at times.

“I was four days in the cold, without light and without electricity,” she says. “It went down to -22°C and -24°C. I had to call the police so that they tell the owner to send an electrician as fast as possible.”

“We hear about many situations of this sort,” Benessaiah points out. “Unfortunately, sometimes, those stories don’t make much noise.”

Ménard is now suing her landlord.

“Social housing truly is a solution because it allows stability to low and medium income individuals, without fears of eviction due to extensions or repossessions,” says Benessaiah.”In the South-West, we estimate that there more than a thousand social housing units needed.’’

Many workers and tenants rights’ organizations attend a protest on April 2.

Cooperatives are one option, allowing tenants to be in charge. The NDP’s Alexandre Boulerice agreess it’s important to fund housing alternatives.

“Non-market alternatives such as social housing and housing cooperatives are what make a substantial difference, since it actually puts a downward pressure on the market,” he says. “Sadly, housing is not yet considered a fundamental right. And this even if we tried three or four times in Parliament for it to be recognized as such.’’

In Quebec, most housing cooperatives and non-profit housing facilities are funded through the AccèsLogis program. But despite rising prices, the program has been under-subsidized for a decade.

Investments and planned investments towards AccèsLogis between 2018 and 2027. Graphic by Victor Tardif.

In February 2022, the Programme d’habitation abordables Québec (PHAQ) was launched to replace AccèsLogis.

The program aims at increasing the housing supply while curbing costs by encouraging new developments. Those may include private sector housing as well as cooperatives and nonprofit housing. Construction can be subsidized up to 50 per cent, but that increases to 80 per cent for nonprofits.

The problem is that PHAQ puts private-sector and community developers in direct competition for government money. The fact that the funds are not entirely dedicated towards nonprofits worries tenants rights organizations, many seeing PHAQ as a means of subsidizing the private sector.

Whether it be through demonstrations, protests or housing committees, many tenants rights activists denounce the housing crisis. Video by Victor Tardif.

“The new policy is yet again, about prioritizing the privatization of housing,” says Benessaiah. ‘’The CAQ government has already completely denied the existence of the housing crisis, so it’s coherent that they continue with such contempt. It is absolutely not a solution to the housing crisis.”

Of the 2,200 housing cooperatives across Canada, 481 are in Montreal. Still, the city has two thousand families on a waiting list for subsidized housing. And activists worry that PHAQ is unlikely to increase the supply enough to handle increasing demand.

A look at the cooperatives in the city. Map by Victor Tardif.

“The under-funding of the AccèsLogis program causes a slowing down of projects for hundreds,” says Mériem Mennai, communication manager for housing group Bâtir son quartier. “The argument given during PHAQ’s launch was that it allowed for projects to be made within one year, unlike AccèsLogis which would take more. From what we’ve experienced, projects could be quickly delivered if adequate and plurannual funding was granted in time.”

When asked about the future of AccèsLogis, Mennai isn’t jumping to any conclusions.

“On the provincial level, no new AccèsLogis units have been announced for more than three years, hence the slowing down of new projects,” she says. “Community housing organizations exhibit worry towards the new PHAQ program and the risk of seeing AccèsLogis disappear, but we do not yet know if the latter will be abandoned.”

A sign in the POPIR offices with a message translating to “social housing is needed.”

Benessaiah is one of those worried about the PHAQ.

“AccèsLogis has been defunded for years. But now, the government’s announcement is quite worrying. The program may be destined to disappear. That would be catastrophic,” she says. “The CAQ government has already completely denied the existence of the housing crisis. So it is in the continuity of this contempt.”