BY Jordan McKay & Myrialine Catule

Myriam Havel has spent her entire adult life surrounded by Montreal’s public art.

“When you live here, I think you stop noticing it,” says Havel. “But whenever I leave the city, I feel like something’s missing.”

Growing up in a suburb of Montreal, public art was far less integrated into the fabric of her childhood, but as she’s gotten older, she says she’s become too used to it.

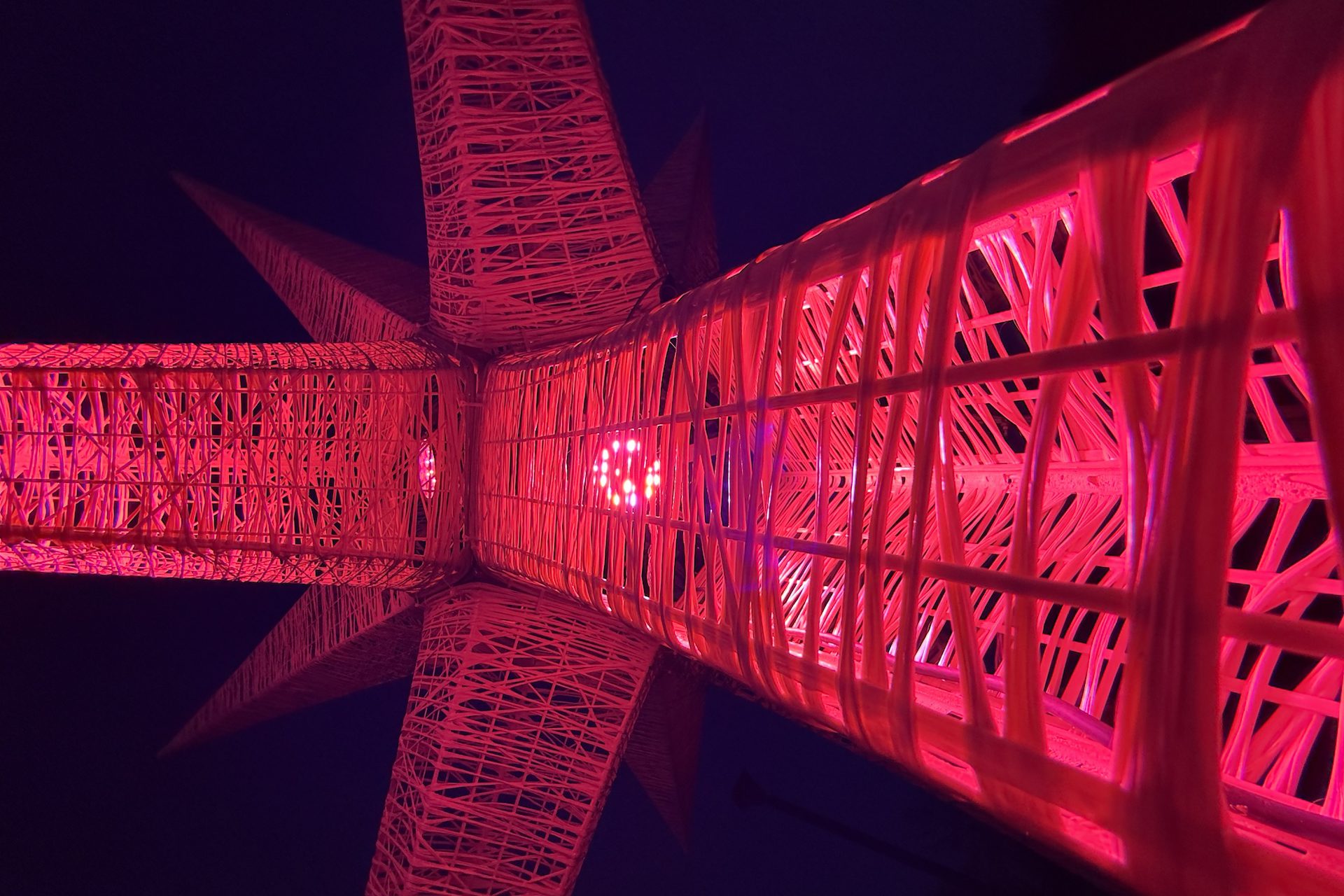

Staring up at Di-Octo II, a public artwork by Anythony Howe, she squints.

Di-Octo II features 18 exterior and interior-facing metal arms adorned with round metal embellishments, which give them a tentacle-like look. Photo by Jordan McKay.

“I’ve never actually taken the time to really look at it,” she says. “It doesn’t stop me in my tracks, but I kind of get it. The longer I stand here, the more I don’t want to look away.”

Perched on the corner of De Maisonneuve and Mackay Street, caressed by a bustling sidewalk, is Di-Octo II. A piece of kinetic art meant to alter the onlookers’ sense of time and space, the structure stands high above the heads of passing people.

The orientation of the metal plates and arms provides Di-Octo II with its movement, allowing it to sway according to the force of the wind. Photo by Jordan McKay.

Since its inauguration in 2017, the artwork has occupied its corner and receives regular tune ups and check-ins from the DL Heritage art conservation company. They ensure all moving functions of the structure are in working order.

The piece is one of over 360 pieces of public art in the municipal collection, and one of over 1,000 throughout the greater Montreal area.

Concentration of public art on the island of Montreal. Map by Jordan McKay.

Despite the large number of public works in Montreal, the city’s 2024 budget allotted just 700,000 dollars to the restoration of only two of the city’s public artworks.

“The maintenance of public art is a big question because it's nice to have art there on the territory,” says Micheline Bélanger, the division manager of cultural activities at Pointe-Claire Cultural Center. “But it's always very difficult to convince the administrators or the city councils that the maintenance of an artwork is important, [and] to put money there.”

Bélanger says that while the city councilors in Pointe-Claire are starting to better understand the general upkeep of public art, it can be hard to get people excited about maintenance.

“There's no wow effect in maintaining a public artwork,” she says.

“In my experience, it seems that the public doesn't really have an opinion on conservation because they don't see it,” says Nathaniel Huard, the marketing and communication director for DL Heritage. “Because the public isn't actively asking for it, or they aren't actively involved. A lot of times with the conservation projects, it seems like politicians are less willing to take the initiative.”

Huard believes conservationists’ goal of going unnoticed in the restoration of public artworks often means people don’t see a need to fix things.

However, despite concerns around preservation, public art continues to thrive in Montreal.

The city’s Art Public Montreal describes Montreal as an open-air museum and, in collaboration with Tourism Montreal, aims to increase awareness of the city as an international destination for public art.

Sculptor Danica Olders says the magic of public art is that “people can just sort of stumble upon it and discover something in a different way than they would have going to a gallery.”

“Twins 6’ Hearts” stands outside the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) and is one of the 27 public works lining the surrounding streets. Photo by Jordan McKay.

The prominence of public art in Montreal can be attributed in part to the Politique d’intégration des arts à l’architecture et à l’environnement des bâtiments et des sites gouvernementaux et publics, which dictates that one per cent of the budget of public construction projects must be reserved for the integration of a public artwork.

Since the introduction of the policy by the Quebec government in 1961, it has led to the integration of roughly 3,500 public art projects, including in the Montreal metro system.

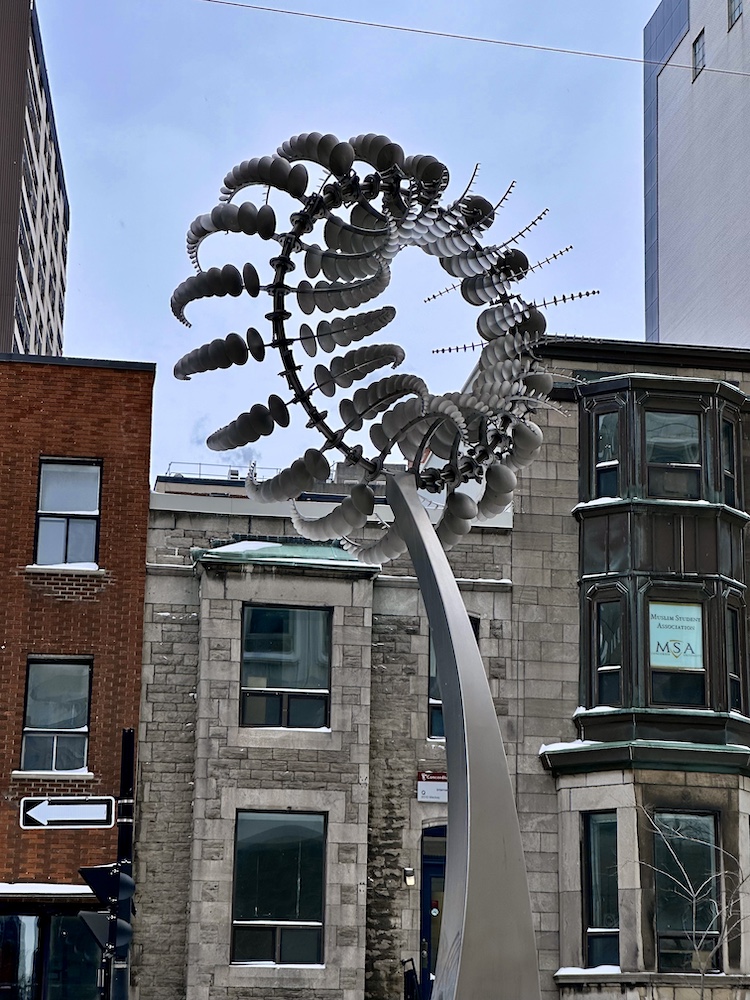

Alongside a cohort of Fine Arts Masters students from Université de Montréal, McGill University, Concordia University, and Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM), Olders took part in a project for the Réseau express métropolitain (REM) as part of the one per cent public art policy.

Older’s students were given free rein and access to materials without cost to build their temporary works, with one sole restriction—they needed to be built sustainably.

For Concordia University Professor Kelly Jazvac, who participated in the project, the focus on sustainability was necessary.

“We're in a sixth extinction event, and not taking this into account in the art we make seems pretty short-sighted to me,” says Jazvac. As a member of the Synthetic Collective, a group of artists, scientists, and researchers interested in plastic pollution, Jazvac believes there needs to be more focus on the impact of public art.

While the one per cent policy is a great initiative for promoting art, she says more could be done to sustainably reimagine it.

“I think the relevance of that program would be to start thinking about how it could also be used for more living works as opposed to flopping one monument and expecting it never to change throughout the course of its life,” she says.

Of course, public art in Montreal is about more than just the city-approved pieces. The city is also a hub for alternative forms of public art, which often feature more adaptable pieces and accessible materials, like spray paint and scrap metal.

Counter narratives to public art are created by street artists. Video by Myrialine Catule.

However, some of the alternative forms of public art can be problematic for maintaining public pieces. While debates about what kinds of street art, like the age-old graffiti versus murals argument, can be considered ‘acceptable’, maintaining approved artworks can come at the cost of the alternatives. Graffiti, for instance, is the most frequent example, especially since it’s not easily removed from stained glass and can result in a lengthy restoration, according to Huard.

While it’s not often mentioned when discussing the integration of public art or the one per cent policy, the Quebec government maintains strict regulations for the preservation of public artworks.

Each public artwork owner is responsible for their piece, including regular maintenance and if needed, additional costs associated with any restorations. Quebec offers a maximum subsidy of 60 per cent of the costs. But it may offer less or none at all.

Habitual maintenance for artworks within but especially those not covered by the policy, can be costly for a city.

A public art installation in Île Bizard is partially lit, with only two of the ten star peaks lit. Photo by Jordan McKay.

“We're trying to have a recurring budget,” says Bélanger. “It's not always the case, but when we have one, we try and do what we can.”

While sustainable pieces may seem like a way to circumvent the low interest in maintenance, according to Olders, the process is the same: "There are instances where it got attacked by birds at one point, or somebody hit it with a skateboard, and we had to go and repair it, patch it.”

In her experience, maintenance is the same, she adds, “unless you just let it be in the natural world and let it change with how things, how people interact with it.”

However, Huard believes that the permanence of some artworks is vital to the cultural fabric of a city.

“Making [public art] benefits future generations. When you don't know where you're coming from, it cuts your roots,” he says. “How long does it take for people not to remember where they come from?”

In Montreal it’s certain that public art is a part of the past and present of the city, with pieces sprinkled throughout boroughs and in public spaces.

“I think it's great for the citizens,” says Bélanger. “The idea is you want people to walk around their town, take the train every day and just to be there and in contact with art.”

"The Memory of Water" a mural by ARTDUCOMMUN decorates an old pumping station in the Pointe-Claire Village. Photo by Jordan McKay.

Despite the inherent connection between public art and Montreal, the current budget for the city only promises a small amount towards the restoration and integration of public art.

Havel says that in the current cost of living crisis it makes sense that priorities are elsewhere.

“I think the preservation of art and public art in general is important, but I also think there needs to be people to enjoy it, she says. “If the city is too unaffordable then what’s the point?”