BY Fatima Dia & Katherina Boucher

When Pamela Fillion moved out of her parents’ home at 16, figuring out how to get food was a primary concern.

“[I had] questions of how and what to cook, and how to balance things,” says Fillion.

After years of activism, and working and studying simultaneously, she took a five years away from her master’s degree to recover from traumatic experiences and work burnouts that led to major disability. Now, at 33, she’s back at Concordia University to wrap up her master’s.

Fillion had gathered an immense amount of knowledge from the work she did during her time as a student at McGill University, having become heavily involved in campus life and organizations promoting social and environmental justice. After graduating, she was hired to work on McGill’s Community Development Day project, and later worked at the Peoples’ Potato at Concordia.

With all that, she created Blueberryjams.

With BlueberryJams, Pamela Fillion offers a variety of homemade products as a means to achieve food sovereignty. Photo by BlueberryJams.

The initiative aims to not only provide an accessible platform for those already involved in social justice and are looking for food sovereignty and system transformations, but also serves as an entry point for people who have never thought about these things.

“When we do food sustainability classes, it’s hard for students when we’re talking about the negatives,” says Fillion. “[With Blueberryjams] we’re starting at a place where we’ve made something, and it’s one small project at a time based on what people are interested in.”

Blueberryjams offers a variety of DIY workshops. A workshop in radical home economics helps people reuse basic home materials. Another teaches folk herbalism, which uses traditional ancestral healing practices centered around sustainability.

Fillion is also a teaching assistant at Concordia, where she helps teach classes about food systems and food sovereignty. Part of the reason Blueberryjams is important to her is that it aims to reconnect people with food knowledge.

“We’ve commodified [food] to such an extent that we’ve become removed,” says Fillion, adding something her grandmother told her. “‘When you were six or seven, they made you hold the pail under the pig to catch the blood so you can make blood sausage.’ It just really struck me that we are so, so far from holding the blood pail.”

Food Sovereignty is defined as the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.

The term was first coined in 1996 by La Via Campesina, the International Peasants’ Movement aimed to coordinate peasant organizations of small and middle-scale producers, agricultural workers, rural women, and indigenous communities from Asia, Africa, America, and Europe.

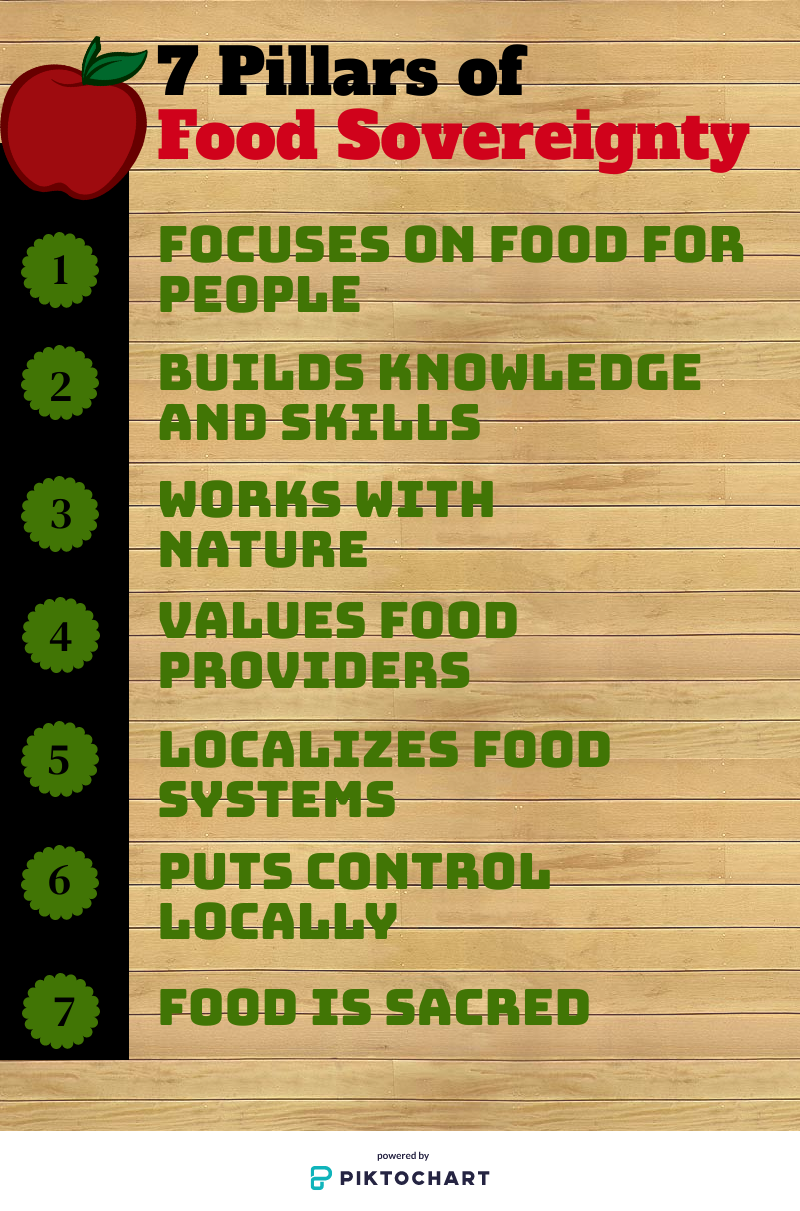

Another organization working towards food security in Canada is Food Secure Canada. To achieve this goal, Food Secure Canada adopted seven pillars of food sovereignty. The first six are: focus on food for people, build knowledge and skills, work with nature, value food providers, localize food systems, and put control locally. A seventh pillar was added later: food is sacred.

The seven pillars of food sovereignty. Media by Fatima Dia.

The food system in Canada is complex and layered and relies heavily on exports and imports.

Erik Chevrier, a researcher and social activist who is currently focusing his research on student-run food groups at Concordia University, describes food sovereignty in terms of process and outcomes.

“Food sovereignty is a process of struggling for better working conditions, for better food conditions, and basically to emancipate food from global capitalism and more into the hands of local people,” he says.

The second, equally important part is outcomes. He explains that outcomes are about establishing what kind of food system the people want.

“It’s a process about achieving better conditions, and the outcomes are the conditions people are trying to implement.”

The seven pillars are a target. But when it comes to application, Canada falters. This lack of proper action is due to the fact that Canada’s centralized economic structure doesn’t allow cultural differences in production.

“For example, if you look at First Nations’ food security or sovereignty, certain places are not allowed to produce and sell certain kinds of foods because it’s being sanctioned by the Quebec and Canadian government,” says Chevrier. “There are different laws about production and distribution that a lot of First Nations perhaps don’t necessarily [have as] part of their eating habits.”

Chevrier gives the example of Greenpeace’s campaign against seal-hunters, which completely disregarded the fact that seal is one of the Inuit’s staple foods.

“So as seen by animal rights activist, yeah we have to stop seal hunting, but in the bigger picture, people don’t really have access to other foods, so it was seen as quite a racist campaign against the Inuit people,” says Chevrier, pointing out that the Inuit’s approach to hunting is still more humane than factory farming.

A study published in 2008 says the sub-urbanization of food retailers in North America has contributed to the emergence of “food deserts,” areas in a city where there’s poor access to healthy and affordable food. Food Secure Canada reports that this is still an issue. Even if inequalities were mitigated, Chevrier says that it’s still hard to say Canada is food sovereign because a lot of the food is imported, even though the country is the fifth largest agricultural commodity exporter of 2016.

A line up at commercial business Premiere Moisson. Photo by Katherina Boucher.

“Most of the food that we produce here goes externally to other markets, and doesn’t necessarily serve Canadian markets,” says Chevrier.

A 2017 study found that many Canadian farmers now rely on jobs outside their farms mostly due to an increase in their expenses. From 1985 to 2007, the dominant suppliers and service providers captured 100 per cent of Canadian farm revenues. By 2016 it was down slightly to 98 per cent.

“These globally dominant transnational corporations have made themselves primary beneficiaries of the vast food wealth produced on Canadian farms,” writes researcher Darren Qualman in the study. “They have left Canadian taxpayers to backfill farm incomes, approximately $100 billion have been transferred to farmers since 1985.”

Farmers are at a record high in debt—just under $100 billion.

“I think people will need to relocalize their food,” says Chevrier, giving the example of Cuba’s urban farms as a solution. Montreal already has urban farms like Lufa Farms and TriCycle, though they’re not large enough to shift the food supply system.

TriCycle’snew farm in Montreal operates entirely in a sustainable manner, in which the products they use, including pesticides, are recycled. What is it that they are farming? Edible insects.

“[The food system] is a wicked problem we need to address and it requires us to tackle different fields of studies to find innovative solutions,” says Co-founder Didier Marquis .

Is eating insects considered food sovereign? Video by Katherina Boucher.

“If we want to become more food sovereign we have to take control over the system, on individual levels, we need to produce more food in our own kind of backyards and other places like that,” says Chevrier.

According to Chevrier, big companies are controlling the food market, and the market is basically being subsidized by the government in order for it to be exported to other countries. Chevrier adds that Canada’s farming system relies on importing foreign workers from undeveloped countries over the summer to do the actual farming.

“We need to drive down the cost of labour by bringing people from countries where they’re willing to work contracts that are way below minimum wage,” he says. “It’s kind of an absurd thing, it really shows how the food system is not functional in a capitalist system, because it’s heavily subsidized, and we rely on wage labour that is under minimum wage continuously.”

The government of Canada released the Food Policy for Canada in 2019. It followed up by investing $134 million to support the policy and build a healthier and more sustainable food system. Part of the policy includes keeping track of the progress towards long-term goals and ensuring transparent reporting of results.

However, there have been no reports regarding any action being taken since then.

With the current COVID-19 outbreak, much international trade has been halted while countries lock down in order to fight the virus. Chevrier is worried that this could result in a food shortage.

“Right now we’re relying on international markets. A lot of our food is actually being imported from other countries, and I don’t know what that means,” he says. “The other day I bought oranges and I realized they were from Spain. Spain is having a major crisis [with the virus], so I don’t know how that’s going to impact the system because apparently the virus stays on surfaces.”

Local Urban Farm Lufa Farms deliver locally grown food to many Montrealers once a week through their online markerplace. Photo by Katherina Boucher.

“The bigger picture is, if we’re not able to produce food and move it around the world, we’re going to have to rethink how this is done. I think the big companies are going to push back against this because right now they have a model that is extremely profitable for them,” Chevrier adds.

Since 2015, six large firms have been steadily dominating the market of seeds and agricultural chemicals: BASF, Bayer, Dow Chemical, DuPont, Monsanto, and Syngenta. Dow Chemical and DuPont had merged in December that year. In 2016, State-owned China National Chemical Corporation (ChemChina) offered $43 billion US to purchase Syngenta, and later that year Bayer proposed to acquire Monsanto. According to Chevrier, it seems as though the Big Six are consolidating.

“It looks like the six companies are actually going to form a multi-conglomerate company that’s going to be the biggest oligopoly in food services,” says Chevrier. “To me, that’s concerning in a way too, that we don’t want these companies to have so much control over resources. This is why it’s complex to talk about food sovereignty when these companies are still controlling the chemicals, fertilizers, seeds, and all of this stuff. Because they have a big hand and are actually taking the profits of the farmers in Canada.”

The topic of food sovereignty can be overwhelming. But Blueberryjams proposes we begin by looking at the basics, starting with the simplicity of where our food comes from.

“It’s the idea of trying to resist the loss of that knowledge. What I’m really trying to do with Blueberryjams is get people to see the inherent revolutionary value of trusting themselves and their communities,” says Fillion.