BY David Earles & Jennifer Fox

When Samantha Callaghan woke up on September 27, she knew something wasn’t quite right.

“I felt myself getting really, really tired,” she remembers. “You get really achy, your back is hurting, and you’re starting to get a weird sensation in your throat. Both of my roommates were also really sick.”

Callaghan was confined to bed for four days.

“I was so sick that I couldn’t stand, I couldn’t walk or anything,” she says. “My pain was quite severe in my elbows, in my knees, my joints, my ankles. Everything felt like pressure, like it was breaking.”

When she was well enough to get back on her feet, she went to get tested at a local clinic. After waiting outside in winter conditions for an hour—still symptomatic—she was triaged and received a nasal swab test.

Forty-eight hours later, she got the call. She had tested positive for COVID-19.

Callaghan’s experience is, of course, not a unique one in Quebec. Montreal in particular continues to be a hotspot for COVID-19, and has seen over 100,000 cases, as well as over 4,000 deaths due to the virus.

However, there is a sizable portion of the population that is actively resistant to the idea of vaccination despite the severity of the pandemic and drudgery of quarantines. Some flatly refuse to be vaccinated, while many more have expressed some degree of hesitancy.

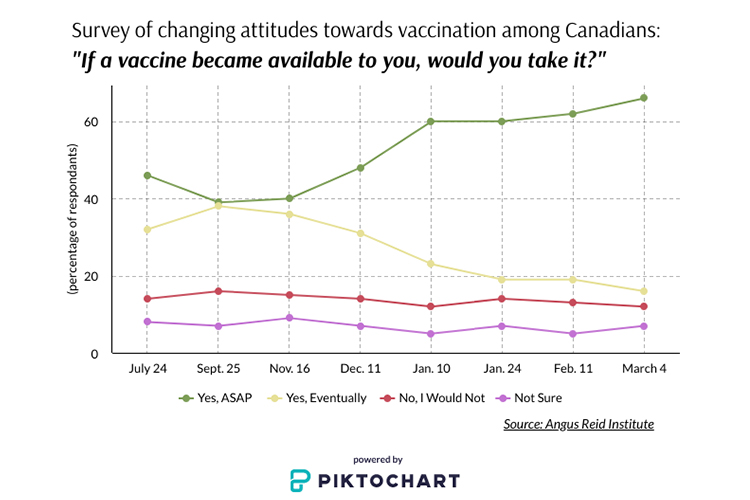

A graph depicting the willingness of Canadians to be vaccinated between July 24, 2020 and March 4, 2021. Media by David Earles.

Kevin L’Espérence is an epidemiologist and researcher at the MUHC in Montreal. He says that, given the circumstances, a certain degree of vaccine hesitancy is understandable.

“First, I understand them because they don’t have the chance to study science,” He said. “That’s normal, that’s okay. We are not all scientists, and we all want answers. This is a period of uncertainty.”

However, he stressed that the benefits of vaccines far outweigh the risks, and argued that the standard of living which is currently enjoyed throughout the western world would be impossible without them.

“If we remember the beginning of the 20th century, more than half of all children were diseased by the age of five,” he says. “What changed that is the development of vaccines. I would say that we should put things in perspective and say well, vaccines are preventing more than three million deaths each year. This is a technology we know, and the benefits of vaccines outweigh the risks, definitely.”

A child care worker gets vaccinated at Maimonides Geriatric Center. Photo by Jennifer Fox.

L’Espérence believes a major part of the problem is caused by a disconnect between the scientific community and the general public. This disconnect can sometimes be exacerbated by false information circulating on the internet.

“People are beginning to mistrust scientific information, and that is scary to me. They prefer to listen to vaccine skeptics like Robert F. Kennedy in the United States,” he says. “This is a person who is very powerful and has a lot of credibility in politics, but is actually presenting scams and false information to the public in regards to vaccination. He’s not an expert but he has that reach.”

The phenomenon of politicization has begun to seep its way across the border and make an impact on Canadians.

“This is what we are starting to see in Quebec and Canada, and that is very scary,” L’Espérence says. “The thing is, vaccine hesitancy should not be influenced by political decisions, it should be influenced by evidence-based decisions.”

Nevertheless, this social media-based politics is adding fuel to the ‘anti-vax’ movement, which is growing here in Quebec and around the world.

Montreal’s Olympic Stadium has been repurposed as a mass vaccination site. Photo by David Earles.

However, vaccine hesitancy in some communities is driven not by politics, but by decades of social inequity when it comes to receiving quality health care. Indigenous communities in particular have strong historical reasons to be mistrustful of both the Canadian government and the medical establishment.

Jaris Swidovich is a Pharmacist and member of the Yellow Quill First Nation. Swidovich argues that given the long history of negative interactions between Indigenous communities and the Canadian government and medical establishment, it’s not surprising to find a large degree of vaccine hesitancy among these communities.

“What is unique for Indigenous folks across Canada is the history of medical experimentation which has been performed on Indigenous peoples, such as nutritional experiments in the residential school system, the experimental tuberculosis vaccine, and even historical and ongoing issues like forced and coerced sterilization of Indigenous women,” Swidovich explains. “These issues all collectively come together to provide indigenous people with good reason to feel hesitant.”

Jaris Swidovich gets vaccinated. Photo by Jaris Swidovich.

“I think that if these conditions had happened to any other group of people, that same group would feel the same,” he says.

He also identifies education and outreach as factors in vaccine hesitancy.

“I think that the education component could have been a lot stronger,” he says. “Indigenous peoples should have been part of every phase of every process related to COVID-19 and the COVID-19 vaccination.”

Swidovich feels that Canada has a long way to go in terms of earning the trust of Indigenous communities, and that representatives from these communities should be more present in the planning stages.

“Indigenous people need to be at every table to make sure that our worldview and our people are reflected in the activities of the government,” he says. “And they need to make apologies and reparations for other historical and current issues like forced and coerced sterilization of Indigenous women, for example. Without all of those things together it’s hard to have full trust and full faith in the government.”

Montréal-Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport Departures Check In board. Photo by Jennifer Fox.

One option being considered by the federal government to get more people to get vaccinated is the use of so-called vaccination passports. They would restrict travel for non-vaccinated people. This approach has already been introduced in some countries.

Will vaccine passports make it easier for us to travel? Video by Jennifer Fox.

However, many fear that this approach would further entrench systemic inequity in terms of access to health care and the benefits of health care.

But Callaghan, L’Espérence and Swidovich all agree on one thing: vaccination should not be mandatory.

“I don’t think that any particular health care service should be mandatory for everyone. It takes away from the autonomy of an individual,” Swidovich says.

“Mandatory vaccination should not be applied at all,” adds L’Espérence. “Ideally, it’s something a person has to have a choice about, to have it or not to have it.”

While she also stated that she felt vaccination should not be mandatory, Callaghan said that it should be encouraged.

“I had COVID once and I don’t want it again,” she says. “It’s important for the safety of the elderly community around us and people who have health conditions. So yeah, do the right thing and get the vaccination.”