BY Evan Jakab & Kayla-Marie Turriciano

There’s a fair bit of baggage involved with the word “therapy.”

A black leather chaise longue and a bespectacled doctor sitting in a straight-backed seat with legs crossed, chin propped in one hand and notebook clutched firmly in the other. Sensibly carpeted floors butted up against sensibly wallpapered walls. Silence, in quantities thick enough to cut with a butter knife.

Harriette the dog does not look like a therapist.

Hariette is an 18-month old Broholmer. On first impression, she does not appear to be anything other than a regular, if very well-trained, pet. She weighs over 100 pounds, enjoys belly rubs, and has bark not dissimilar to that of a basset hound played through a megaphone the size of Texas.

And yet Hariette is a trained animal therapist, capable of recognizing signs of distress both subtle and overt and intervening. Harriette nuzzles my hand repeatedly over the course of my interview with Gaby Dufresne-Cyr, her owner and trainer.

“Oh yeah,” says Dufresne-Cyr. “She’s on the job right now.”

Hariette, an 18-month-old Broholmer, is a trained animal therapist. Photo by Kayla-Marie Turriciano.

Dufresne-Cyr is an animal behavioural consultant, dog trainer and owner of the Dogue Shop, an animal behaviour and training school which also conducts animal-assisted therapy with at-risk teens, mostly by way of dogs.

Animal-assisted therapy has rapidly gained traction as a legitimate provider of psychological care, with the Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association and the American Counseling Association endorsing the practice. Dufresne-Cyr herself works alongside traditional therapists and has had patients recommended to her.

“I see it as a complete alternative [to traditional therapy],” says Dufresne-Cyr. “Obviously, we try to reach the same goals as common therapy, but we’re different because of our lifestyle. My work comes with me at home every day.”

The effectiveness of animal assisted therapy is further reinforced by the training that these dogs undergo—therapy dogs are trained to become emotionally bonded to their charge.

“[The] animal becomes very attached to that person,” says Dufresne-Cyr. “When we go back a second time, then the animal remembers and seeks out the exact person it was working with before. That too impacts their own perspective of themselves: I’m valuable since this animal wants to make contact with me.”

Animal-assistant therapy is becoming a popular way to reduce stress and anxiety. Photo by Cristina Sanza.

Animal therapy, Dufresne-Cyr explains, is more than being allowed to pet some furry critters and going on with your day. The very process of being around an animal and attempting to train it is integral to the experience, as its goal is to force the patient to change their own behavior in a permanent fashion.

Therapy, after all, is more than just a stress release valve. If that’s what you’re after, the Rage Cage has you covered.

After all, no therapist would insist on a patient wearing head-to-toe plastic coveralls, a paintballer’s mask and body armor. Most would object the accessories on offer, ranging from well-worn crowbars to battered aluminium baseball bats.

For most, those implements are held in the same way a headsman would wield an axe, gripped in two hands and held high above the head. Instead of the neck of a bread thief in medieval Europe, however, the target of such focused aggression is something along the lines of a frosted glass vase or a VCR player.

For some, the idea of smashing random objects is key to de-stressing. Photo by Kayla-Marie Turriciano.

First, a bit of background: the Rage Cage is a popular attraction at Sports de Combat, best described as a recreational sports centre specializing in unconventional recreational sports. Think archery lessons, axe throwing and large-scale NERF battles.

While the Rage Cage and similar attractions can be recommended by a licenced therapist as a valid method of de-stressing, they are not intended to be viable, long-term replacements to actual therapy.

Nor, as Bryan Nguyen, the business’s owner and manager, are they intended to be.

“It’s a quick, easy way [of relieving your frustration], but it’s not a form of therapy if you’re talking about chronic issues […] the Rage Cage is not a form of therapy in that aspect,” says Nguyen.

Take a look inside Montreal’s Rage Cage. Video by Kayla-Marie Turriciano.

However, people’s complete willingness to brand the Rage Cage’s unique form of stress relief as “therapy” does expose certain deficiencies in Quebec’s mental healthcare network.

Quebec implemented the Quebec Mental Health Reform Act in 2005, which aimed to improve access and the quality of care of the province’s mental healthcare network. While the act did prove successful in improving some aspects, its impact was felt more heavily in the dedicated mental health care facilities rather than the array of general practitioners working at medical clinics.

People, it would seem, are looking at increasingly novel ways of taking care of their mental health.

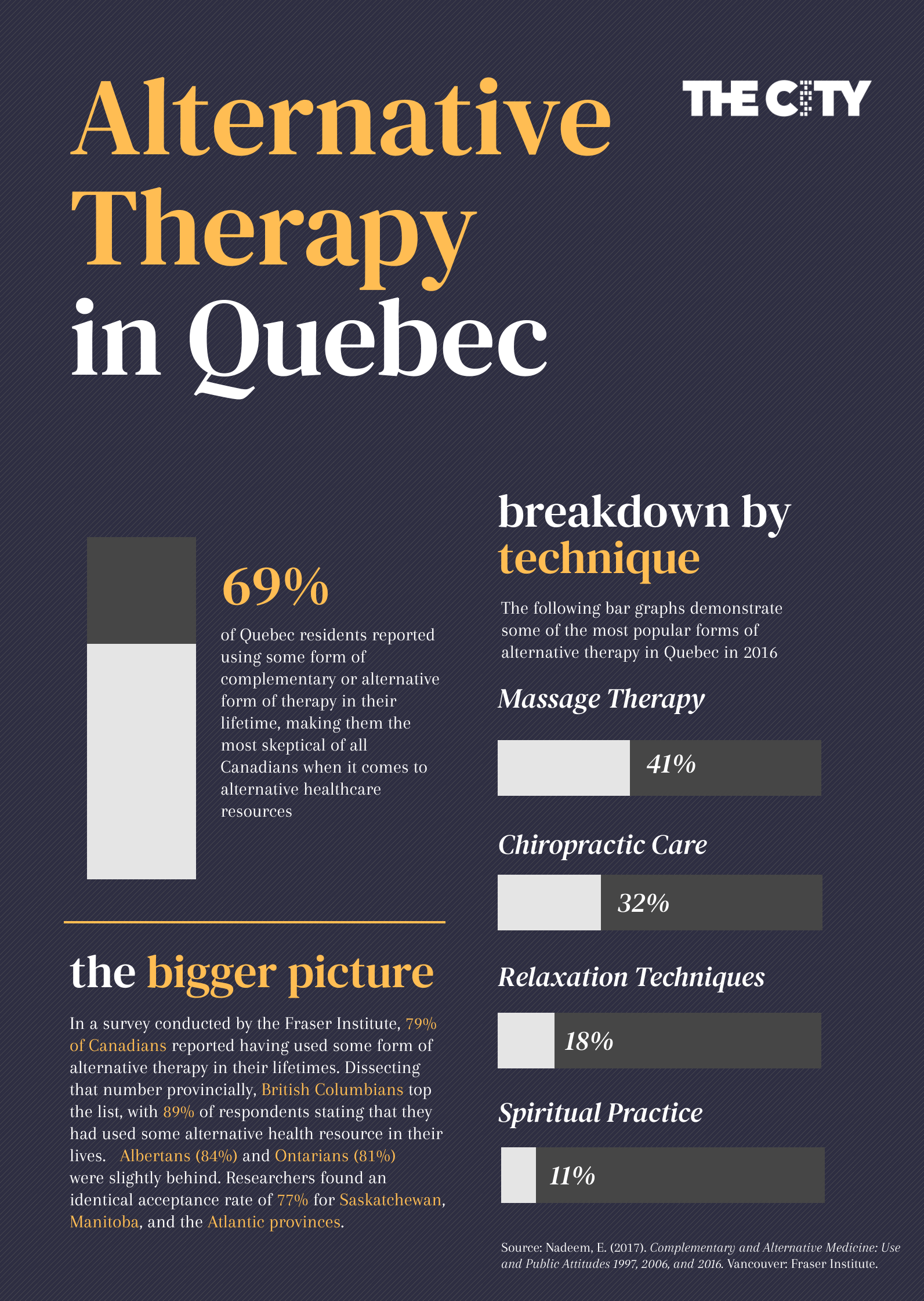

According to a survey conducted by the Fraser Institute, “[More] than three-quarters of Canadians (79 per cent) had used at least one complementary or alternative therapy sometime in their lives in 2016.”

Therapy is an inherently personal process and what may work for one person might not for another. Thankfully, there’s no shortage of alternative therapy methods.

A glimpse into alternative therapy usage in Quebec, compared to other provinces. Media by Evan Jakab.

Sabrina Landecker is an art therapist and vice-president of the Fibromyalgia Association of Montreal. Art therapy, for the uninitiated, is a form of therapy in which an individual is encouraged to create art pieces, primarily paintings, drawings, or sculptures, in order to visually express unconscious thought. Landecker sees its effectiveness as being rooted in the practice’s built-in freedom of expression.

“The creation of images can offer an expressive outlet for when words can’t express thoughts, feelings, experiences,” she says. “As well, the images can become very symbolic and powerful due to the nonlinear quality of an image compared to language that has multiple rules such as its syntax, grammar, logic, [and] spelling.”

She views the role of art therapy as more than just a complement or a replacement to traditional therapy.

“Some people may need a more specific treatment regarding a specific diagnosis, and different therapists have different qualities that can communicate well with one another, which can offer different sources of enlightenment for a client,” says Landecker. “I know regarding chronic pain, the treatment recommended is a mix of [medication] with alternative and complementary therapies.”

Alternative forms of therapy seem to be gathering steam in the province. And the coronavirus isolation could help since forms of therapy that don’t rely on going to a doctor’s office may rise in popularity.

“I believe the population relies too much on traditional therapy,” Landecker says. “Thinking they have all the answers and treatments, but a cure for everything has not been found yet.”