BY Ana Rubio & Autumn Darey

During the height of the lockdown and COVID-19 regulations, Lindsey Glasspole had to say goodbye to her mother.

“In 2020, my mom was going through chemotherapy for cancer, and I think that year I just started looking into death, it being more in my face than it had ever been, not that anyone in my family wanted to admit it,” says Glasspole. “After my mom was given palliative care status, and she wasn’t going to get better, it was sort of a matter of how long she had.”

Gravestones in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges Cemetery. Photo by Ana Rubio.

For her, it seemed natural to find someone outside of her grieving family and close friends to rely on during this painful and delicate time.

“Why wouldn’t we have that?” asks Glasspole. “We have doulas for birth, and death is also a stage of life, so it makes sense you’d have someone to support you in the end of your life, that’s not about wills, or documents, or booking a funeral, or other things we think about when we think about death.”

The COVID-19 pandemic – and the series of lockdowns accompanying it – has remodeled how humans deal with grief. It has opened the floor for the tradition and practices of death doulas to repurpose themselves to the current world.

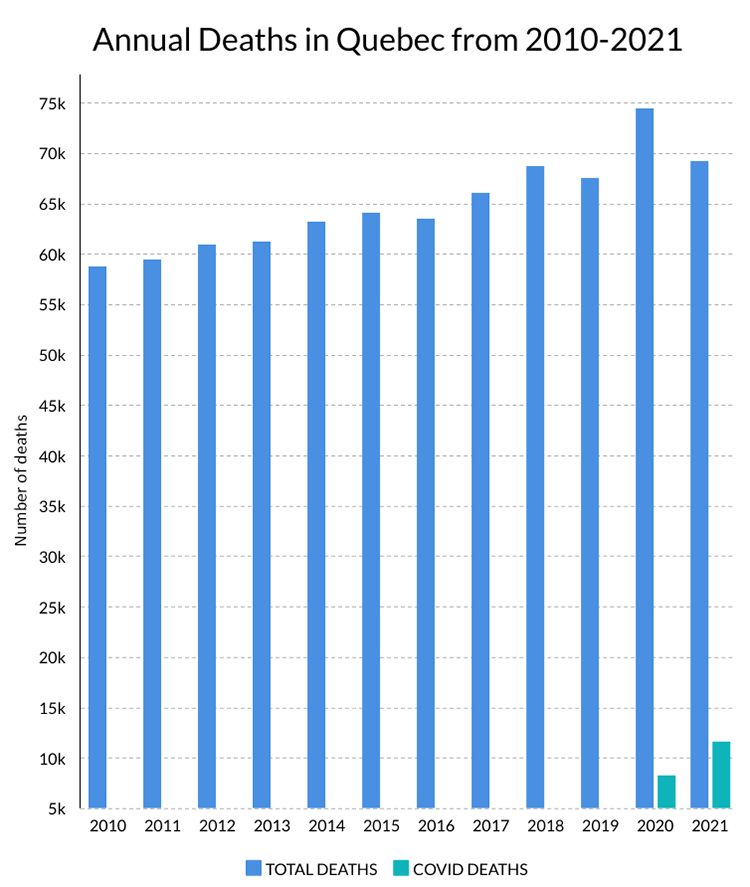

Deaths in Quebec from 2010 – 2020. Media by Ana Rubio.

A death doula or thanadoula is someone who accompanies those approaching their end of life, providing support and space for the needs of everyone involved in this process.

“I will help people figure out what they need to be comfortable when they are approaching that time. Figure out what they need post-death, what kind of legacy they want to leave for people,” says Sue Phillips, a practicing death doula. “Help them understand what kind of legal paperwork they need to have, but also what kind of personal paperwork that can accompany their legal documentation.”

“It is growing leaps and bounds now,” says Phillips, director of the End of Life Doula Association of Canada. “I think it is just starting, because of the efforts of people like myself and others, I am very committed to raising public awareness on the work we do.”

A path leads to gravestones in Notre-Dames-des-Neiges Cemetery. Photo by Autumn Darey.

Lindsey Glasspole went through this transformation and adaptation of death doula practices alongside her doula, Sue Phillips. She had to process losing a loved one in isolation.

“We knew she was going to die; the worst part was the loneliness.”

“My mom was cancer-free for three months, and then, in September of 2020 her cancer came back, and she had to start chemo again, and then very quickly things began deteriorating and she ended up in the hospital,” says Glasspole. “Luckily we were still allowed to go to the hospital, one person at a time, my dad or myself. But then, there was a COVID outbreak at the hospital, so they locked the hospital down.

“My mom was alone for three weeks. Over christmas. Over her birthday. My birthday. We couldn’t see her. My dad really believed she was going to die alone in that hospital, without anyone next to her.”

Standing pillars and gravestones in the Notre-Dame-des-Neiges Cemetery. In the background stands the Saint Joseph’s Oratory of Mount Royal. Photo by Autumn Darey.

Cynthia J. Brunelle is a palliative care volunteer who became a death doula just before the pandemic began.

“Certainly people are talking more and more about death than ever because we talk about how many people die everyday from covid, we never experienced that much knowledge about the death rates in Quebec. It’s been putting our work into light but at the same time, the access for us to be actually at the side of our clients is sometimes compromised because of the restrictions,” she says.

Brunelle finished her 40 hours of practical services to become a death doula right as the pandemic was beginning to surface in Canada. She, like many other doulas, nurses, hospital and hospice volunteers, began her work during a time of need, and now only knows how to provide care through a COVID-19 lens.

“I think Quebec is pretty open about end-of-life care, and how to make it better,” says Brunelle. While alternative funeral services such as green burials are still in the process of being regulated and popularized in Quebec, end-of-life care and palliative care are effectively growing in the province, despite the disruption that the COVID-19 pandemic brought to our lives.

The death care and funeral industry are trying to modernize, but current legislation is holding them back. Video by Autumn Darey.

“In Canada it’s similar in every province, it’s not more complicated here than it is in Ontario for example,” says Brunelle. “We all have a procedure and it’s pretty much the same. We can say that in every province it’s gonna take between 9 months to a year to finalize all the papers and be done with every detail.”

Nancy Richards, director of Cybele School for holistic practices is a doula and death doula, and she explains her relationship with servicing someone in such crucial moments in their lives.

“It’s really similar actually because it’s the life transition, it’s the great beginning, it’s the great end, you feel vulnerable, you are vulnerable. It’s the same thing, sometimes at the beginning of life you have death, sometimes the mother, sometimes the baby so you need to be prepared, it’s a possibility.”

Portrait of thanadoula Nancy Richards. Photo by Ana Rubio.

Glasspole says that trying to grieve during the constantly changing conditions of the pandemic took a toll on her and her loved ones.

“COVID made grief really hard,” she says. “My dad has joined a hockey league, and he’s curling, working so hard to build a life for himself without my mom, and then everything gets shut down.”

However Glasspole says death doula Sue Phillips provided the family with the emotional and spiritual support they needed.

“Sue worked with my dad and I on an online end-of-life ceremony for my mom. We couldn’t have any kind of funeral. And honestly it was a bit better, in a way, how we did things. We have family and friends all over the world, and so we were all able to come together,” she says. “We showed pictures and we played music, and we had friends and family talk about her, and it was beautiful and Sue planned it all, took care of it all, and took that weight off of us, which was amazing. I wouldn’t have been able to do it at that time.”