BY Mina Collin

“Education is a right, it should not be a privilege of people who have means,” says Clémence Bergeron, a student at Ahuntsic College and vice-president of the AGECA student association.

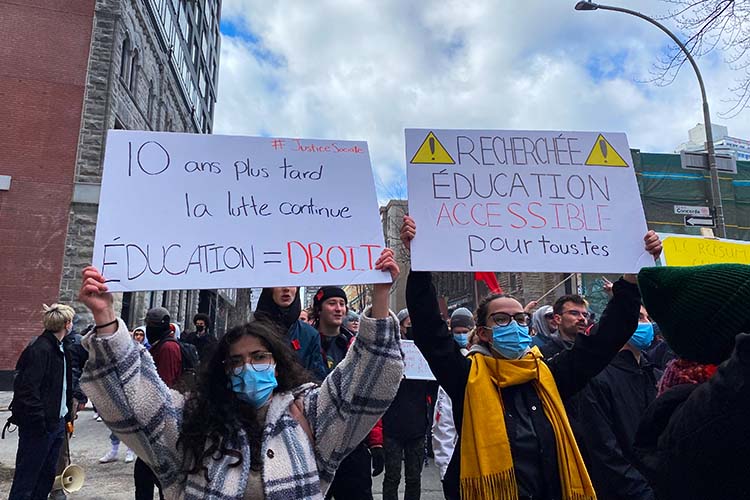

Hundreds of people gathered in downtown Montreal on March 22 calling for free tuition.

“I don’t think it’s right that some people have to choose between paying rent or paying school,” Bergeron says, pointing out that when inflation is spiking, it is more and more difficult for many students to continue their studies.

Hundreds of students marched in the streets to demand free education on March 22, 2022. Photo by Mina Collin.

Rising tuition and inflation are weighing on Raphaelle Pino, a self-supporting student.

“You know, working in addition to school, it’s a full-time life we spend supporting ourselves. We’re clearly going to have to work more now,” Pino says.

The March protest came ten years after the Maple Spring demonstrations. They were marching to prevent a tuition hike. But now students are asking for more: Free education.

Students hold a banner in front of the spot where people spoke just before the march. Photo by Mina Collin.

Even though the Maple Spring protestors won their battle, fees have still increased each year. In Quebec, the cost to attend university now is $4,310, up from $2,506 in 2006. That’s an annual increase of $111.

For many who were present at the protest, including Yannick Delbecque, a professor who supports the student’s demands, the victory in 2012 was only partial.

“We still have a mechanism for indexing tuition fees, which remains a form of increase… So in 2012, we didn’t completely block that, we only limited the increase to a certain level that seemed socially acceptable,” he explains.

A short history of university fees in Quebec. Timeline by Mina Collin.

According to Cedric Picard, AFELC-UQAM’s business manager, indexing tuition to inflation can be problematic since incomes do not grow equally in society.

“It’s not enough to guarantee financial security for people who are simply trying to get an education, which is a right in a democratic society,” he says.

Billions of dollars available to students

As students took to the streets, Quebec’s new budget was released, including $342 million to enhance financial assistance programs for higher education. Interest on student loans is once again waived for the year.

According to Danielle McCann, Minister of Higher Education, these measures increase accessibility to higher education, but the CAQ government is not considering free education.

“It goes into the pockets of students in another way,” says McCann. “Basically, I think we have the same goals, but the means are perhaps a little different.”

Many students and teachers wore red, echoing the Maple Spring. Photo by Mina Collin.

In recent months, the Legault government has also announced the implementation of $1.6 billion in Quebec opportunity grants in five major labour shortage areas.

“These scholarships are a start, but often they are allocated to specific programs according to the needs of the government. And what this does is it merchandises education,” Picard says. “We say we’ll help you pay into your education fund if you do us a favour afterwards, so it becomes very transactional. We put money in so that afterwards, the money comes back into our pockets.”

“I was talking about commodification, that it becomes like a service for which one pays rather than an essential to life in society,” Picard says.

Free education: a possible project for society?

In 2014, a study was conducted into the relationship between access to university education and tuition fees in Quebec and Ontario. It found that tuition increases reduce access to university and that adult students are most affected by tuition increases.

According to one of the researchers of the study, Pierre Doray, however, free education is not a miracle solution, and the money would be paid sooner or later by the students.

“One possibility would be to raise taxes to further fund universities and make up the difference between the current budgets, where a significant portion comes from tuition fees,” he says.

Pierre Fortin, professor emeritus of economics at UQAM, agrees. According to Fortin, free education is a realistic project, but to achieve it, taxpayers’ taxes would have to be raised. And he is concerned about who would pay for the deficit.

“You would make people who are poorer or middle class pay to finance the enrichment of the people who are already the richest in society. It’s much more this question of sharing the wealth that I have in mind,” he says.

Fortin notes that 90% of the cost of university education is already paid by taxpayers. He believes that it is not a bad thing that the student must pay the remaining $4,310.

“The less it costs, the more people tend to waste. When it costs nothing to repeat a year of university, you can go left, right, from one program to another. It doesn’t cost you anything… [The fees] are an important incentive to not waste the resource that is university education,” Fortin adds.

Two students at the free education march holding signs. Photo by Mina Collin.

Others, however, believe that the value of higher education in society must include access for all. According to Chloé Domingue-Bouchard, head of Québec Solidaire’s Thematic Commission on Education, free education would have several positive effects on Quebec society.

“The more educated we are, the more we have a population that earns well, that needs fewer social services, that is healthy,” Domingue-Bouchard notes. “When we have a university degree in general, our annual salary is higher than if we have a high school diploma. So society is logically richer if you have a degree and if you are a qualified worker. You then pay more taxes.”

Domingue-Bouchard believes that it is time to stand out by making choices that will be positive in the long run. The money is there, it’s more a question of political priority.

Many students feel the same way and have been left wanting in the last ten years.

“It’s a never-ending battle, and at some point, we’re going to have to find a solution to solve this problem because the problem is not yet solved,” says Cybill Bou-Nassif, surrounded by her CEGEP friends wearing red squares at the march.