BY Gabriel Guindi & Alexandre Taddeo

On the eastern side of the island in Montreal, Josée Desmeules, a member of Mobilisations 6600 Parc-Nature MHM and her group held a vigil for a recent green space that was recently overtaken by a condo development. It’s another green space gone in an area that desperately needs it.

“The destruction of ‘Boisé Assomption’ will create so much more soot between the road and the highway that the trees could have absorbed,” Desmeules says.

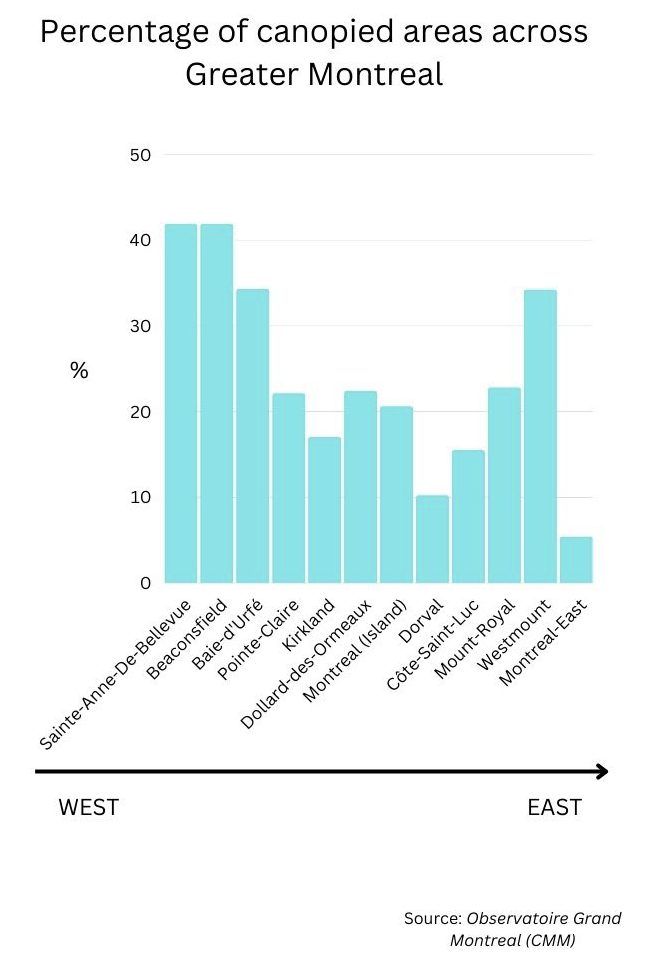

Industrialization in the east has resulted in less green space when compared to the rest of the island. The Mercier-Hochelaga-Maisonneuve borough, a big portion of Montreal’s east end, is one of Montreal’s lowest canopied areas, with shade from greenery totaling only 13.79 per cent compared to an average of the whole island of Montreal at 19.4 per cent.

The Assomption-Sud-Longue-Pointe sector, known by some as ‘the black lungs of Montreal’ due to the overall air quality of the district, has gotten approval by city council to build condos on a private green space formerly known as ‘Boisé Assomption.’

“It’s hard for us to accept the fact that the same effort isn’t put [out] for a green space in the east,” Desmeules says.

The condo development site formerly known as ‘Boisé Assomption’. Photo by Gabriel Guindi.

In November 2022, city councillor in Mercier-Hochelaga-Maisonneuve and adjunct leader of Ensemble Montreal, Alba Zúñiga Ramos presented a motion to council highlighting five potential sites that could become protected green spaces in her riding.

Despite one of them being ‘Boisé Assomption,’ four spaces remain as potential sites. However, one of the sites is now facing the same threat of becoming future condo developments

“We see that two of the five that we wanted to protect are in danger right now and we have serious doubts about what’s going to happen to the other three,” says Zúñiga Ramos.

Both lots, according to Victor Wong Seen-Bage, Projet Montreal Communications officer for the mayor of Mercier-Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, were under the same PPU (Programme particulier d’urbanisme), a motion that outlines how a public area will be developed.

These factors, along with the geographic location of the lots, would make the green areas difficult and expensive to purchase from their respective owners.

Despite the approval of the motion to accelerate the purchase of the green spaces back in 2022, asking for the land to be purchased by the city, according to Zúñiga Ramos, the motion was cancelled two months later by the current administration.

“From what we understood at the time, they felt like something needed to be protected because we all agreed on the motion, and two months after we see that they gave a permit for the construction,” says Zúñiga Ramos.

“We cannot engage ourselves to protect these lots in particular because they are not ours,” says Wong Seen-Bage, regarding the initial refusal of the motion.

‘Boisé Assomption’ condo project will comprise of four complexes totaling 1000 housing units, ultimately converting the whole green space into condos. Photo by Gabriel Guindi.

Wong Seen-Bage says the opposition did in fact submit a motion, although initially it was declined due to specificity regarding the lots in question.

A second pass of the motion did in fact get approved by all members of the Mercier-Hochelaga-Maisonneuve council, but it was written in a generalized manner.

“We thought it would be wiser to just remove the five names and just adopt a motion to protect more greenspaces in the borough in general,” says Wong Seen-Bage.

Problems concerning green space protection are due primarily to private ownership and their unbalanced distribution across the island according to Jeanne-Hélène Jugie, leader for environmental based solutions at Conseil régional de l’environment de Montreal (CRE-Montréal), an independent firm dedicated to protecting environmental space on the island.

Private ownership of unregulated green spaces, especially in industrial areas like in Montreal’s east-end could complicate matters for government officials and residents wanting these spaces protected. Photo by Gabriel Guindi.

Despite Montreal’s prior administrations setting benchmarks goals regarding protected space goals to be met by 2031, eight out of the 10 per cent goal of preserving protected space has been attained, while only 10.1 per cent out of the 17 per cent goal to preserve land in the greater Montreal region has been achieved.

“One of the biggest problems present is an imbalance between the west and east of the island. There is a lot more nature in the west than there is in the east,” Jugie says.

Percentage of canopied regions on the island from West to East. Infographic by Gabriel Guindi.

Jugie attributes history, dense neighbourhoods and industrialization in the east as determining factors leading to a lack of green space.

In 2019, the federal government granted $50 million to the city of Montreal to develop a 30km space known as Le Grand Parc de l’ouest on the west side of the island. In contrast, the eastern part of Montreal has always been the hub of industrialization, hence less green space.

“The sector has an important history in Montreal’s industrialization,” Desmeules said. “We’ve had a steel mill, we had a shipyard, and factories, we have a heavy industrial past including a lot of polluted land.”

Though the area is less industrial than before, many areas in the borough lack green space resulting in a lower quality of life for residents.

The general quality of life here in Montreal east is worse than on the rest of the island.

The east is exposed to the highest density of urban heat islands in the city, resulting in many of the borough’s elderly people, accounting for nearly 40 per cent of the municipality, vulnerable to the hotter temperature in the area.

During a massive heat wave in 2018, Montreal-east fell victim to the highest number of deaths in Montreal, totaling 66 deaths from June 30 to July 8.

“We’ve suffered two times more deaths than any other borough in Montreal,” said Desmeules when speaking on the 2018 heat wave. “The general quality of life here in the borough is worse than on the rest of the island.”

The East borough of Mercier-Hochelaga-Maisonneuve is 96 per cent hotter than other metropolitan neighbourhoods in Montreal while having 87 per cent less vegetation.

A result of less green space has contributed to a lower life expectancy in the east of Montreal, at 1.4 years less than the west, while general hospitalizations are also higher, at 809 per 10,000 compared to 695 per 10,000 in the west.

“We know that it is an area that is quite industrialized and obviously the air is not as pure as it would be in other places in Montreal,” says Zúñiga Ramos.

With the growth of the population, there is an increase of residential development leading to the destruction of greenspaces. Maple syrup producers are afraid to lose the lands they have known for generations. Video by Alexandre Taddeo.

On the western island, member of Save Fairview Forest, Geneviève Lussier has stood alongside supporters on the corner of Brunswick Boulevard and Fairview Avenue every Saturday for more than two years, hoping to prevent a local forest fall victim to a development project.

Pointe-Claire is also subject to many high density areas of urban heat islands. Residents like Lussier fear that it can get continuously worse. Compared to other Montreal neighbourhoods, the area is currently 64 per cent hotter while having 61 per cent less vegetation than other areas on the island.

“Without this forest this area would be quite a lot warmer and we already know we can’t afford to lose anymore forests like this,” Lussier says.

“There’s no other forest like this north of the [Highway] 40 in Pointe-Claire,” says Lussier, referring to the wooded area next to the Fairview Pointe-Claire shopping mall.

Genevieve Lussier, member of Save Fairview Forest, stands alongside supporters on the corner beside the forest their group is trying to protect. Photo by Gabriel Guindi.

The forest is owned by Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited, who announced back in 2020 that they would repurpose the forested area into an urban downtown core for the West Island, similar to what occurred in Brossard when green space was converted to what is now known as the Quartier DIX30, an open-air shopping centre.

“It really is the last remaining green space and it is a miracle that it’s remained like this for so long,” Lussier said. “Fairview Forest is one of the last forests that’s privately owned.”

Moreover, the main focus for elected officials in the east-end of Montreal is to improve the quality of life for residents who are living near a soon to be freight transportation area purchased by Ray-Mont Logistics, that could see over 1000 trucks pass through every 24 hours.

In 2016, the Quebec government finally authorized Ray-Mont Logistics to begin construction despite pushback from city officials.

“This is not something that we wanted to happen that quickly at the borough level, we know there are many issues with noise and air quality with residents living near the site, but there are green spaces around that could be protected so we could plant more trees to create that buffer zone so that the quality of life of these residents are protected,” says Wong Seen-Bage.

Currently in the east, Projet Montreal has planted 2500 trees annually, making it a cheaper alternative rather than buying private green space.

They will continue to fulfill that goal until the end of their term in 2025.

“We want to increase the amount of green space in the borough as a whole, and it’s easier to do this on spaces that we own […] these are easy measures the borough can implement and make a difference,” says Wong Seen-Bage.