BY Nanor Froundjian & Diona-Rosan Macalinga

When Kren Clausen moved to Old Montreal 17 years ago, the area was in the beginning phases of some major developments.

Over time, he witnessed a change in the neighbourhood with the addition of tall, modern buildings in the districts surrounding Old Montreal.

“You just have a different feeling, vibe, when you walk in your town,” says Clausen. “It’s not the quaint, charming, original town that it was 20 or 30 years ago.”

The historical and cultural aspects of the neighbourhood are what initially attracted Clausen to live in Old Montreal. “I often thought how I would like to live in a historic venue filled with rich history, heritage, vintage buildings, narrow cobblestone streets similar to many old parts of Europe,” he says.

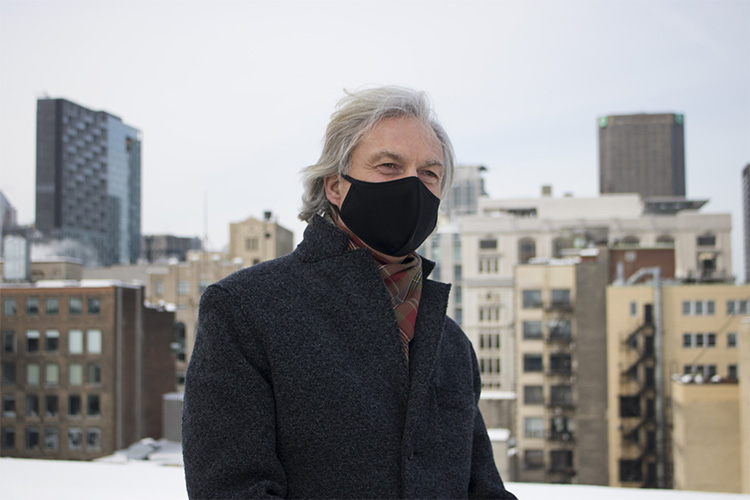

Kren Clausen moved to Old Montreal 17 years ago for its old European charm. He wishes more would be done to keep as much of the old city’s character intact. Photo by Nanor Froundjian.

The newer buildings dwarf those built in past centuries. Many residents worry the new developments are crowding the landscape of Ville-Marie.

“Usually that means higher density and higher buildings, and this creates a closed-in environment for the old town,” says Christine Caron, president of the Residents Association of Old Montreal. “You lose perspective.”

She explains that the look of new buildings clashes with the historical architecture in the area, a concern Clausen also shares. He suggests that maintaining harmony between the old and new—both architecturally and aesthetically—is crucial to create a feeling that is in keeping with the character of the neighbourhood.

Caron points to a few development projects she describes as very “badly integrated” with the surrounding areas where the styles of the contemporary structures did not mesh with the historical ones. She notes that other projects like the office building at the corner of De la Commune and McGill streets were more successful.

Residential units were added on top of the Former Royal Bank at 221 St. Jacques St.—originally built in 1907—depicting an example of a recent addition to a historic building. Photo by Nanor Froundjian.

The city says their primary role is to make sure new projects respect urban planning regulations.

“The staff of Ville-Marie’s Direction de l’aménagement urbain et de la mobilité obviously makes developers aware of the importance of obtaining the highest possible level of social acceptability for their projects and works with them to help them improve them,” says Anik de Repentigny, a media relations officer for the City

For projects that require amendments to the urban planning regulations, the Office de la consultation publique de Montréal can intervene to provide suggestions with the objective of “[maintaining] a certain unity in an environment that has a heritage value,” says Luc Doray, general secretary of the OCPM. “It’s really to maintain the spirit of Old Montreal.”

“All of this is fragile,” he says, about conflicting interests in development projects since everyone doesn’t attribute the same value to certain monuments or places.

Since Old Montreal is a heritage site, there are strict regulations to preserve old buildings, many of which have become landmarks in the city. Any modification, renovation, construction, repurposing of buildings must be approved by the Ministère de la Culture et des Communications. Outside of Old Montreal, projects must abide by the urban planning regulations of the Ville-Marie borough.

How old buildings are preserved and repurposed for modern use. Video by Diona-Rosan Macalinga.

“There’s a way of incorporating new with old tastefully and respectfully,” says Karim Boulos, a real estate consultant. “So there is that reality that you can take an old property, develop it further, or build next door to it, and still maintain a sense of communication between the two properties.”

“The development is going to happen,” Boulos continues. “It’s a matter of integrating it in an intelligent fashion.”

More than 11,000 residential units were built in Ville-Marie between 2015 and 2020. Nine thousand more residentials units have been started since 2020.

Although the height of buildings seems to be the main concern for the residents, from an urban planning and real estate development perspective, the advantages sometimes outweigh the shortcomings.

[slide-anything id=”4536″]

“When we densify a neighbourhood, we don’t want mushrooms—we don’t want these outcroppings that don’t have any relevance with their neighbours,” Boulos says.

He explains that it is worthwhile to build tall buildings in clusters that are very dense, meaning that the buildings cover a small portion of the lot but keep a large square footage and more green space by having many stories.

One issue when it comes to height regulations are the zoning bylaws for each district that dictate the restrictions to control the use of land. According to the Ville-Marie borough’s height restrictions, the majority of the buildings in the district of Old Montreal cannot be taller than 23 metres—or six stories—with smaller areas that can go up to 44 metres.

The building height restrictions for Old Montreal and its surrounding areas. Media by Nanor Froundjian.

However, for new developments, the zoning bylaws can be amended to suit a specific project.

“There is no such thing as 100 per cent perfect zoning,” says Boulos. “Urban planning is really about designing a neighbourhood, and what goes where becomes very important, and how it’s built becomes secondary.”

According to Boulos, the primary focus of development should be the logical structure in the grand scheme of things.

The days of the house with the white picket fence are over—we cannot afford to build those kinds of very low density developments.

In an attempt to draw in a wider demographic to allow more diversity in the Ville-Marie borough, and all around Montreal, the Plante administration drafted the Bylaw for a Diverse Metropolis, also known as the 20-20-20 Rule, to promote the construction of affordable housing in the city. The bylaw, which came into effect on April 1, 2021, stipulates that new large residential buildings must include 20 per cent social housing, 20 per cent affordable housing, and 20 per cent three-bedroom units.

Since the city cannot afford to buy the land they wish to develop as property prices are very high right now in Montreal, nor can it forbid land owners to proceed with development projects, imposing regulations on developers is a viable method of monitoring these new residential projects.

But developers in Montreal are finding that this bylaw might have the adverse effect and instead push developers out. The city said they cannot yet comment of questions that are still hypothetical.

“The days of the house with the white picket fence are over—we cannot afford to build those kinds of very low density developments,” says Miguel Escobar, founder and CEO of Future Cities, whose international career as an architect and real estate broker spans more than 35 years. “The fact is that we need more development, much more than there is going on right now and the city’s actually putting on the brakes instead of promoting new development.” He says developers cannot necessarily make revenue on their investment by adhering to regulations aiming to make housing more affordable.

Pedestrians cross the street in Old Montreal. Photo by Nanor Froundjian.

According to Escobar, there needs to be more development in order to satisfy the demand for housing and to keep property prices from rising.

“When you have 45 people making an offer on the same house, that’s the sign of a real big problem,” he says.

There is sometimes a disconnect on the communication level between residents, developers, and the city regarding the process to implement new buildings that not only focus on presenting a single development, but that also show the rationale behind the planning. Boulos and Clausen say that the process is not always as transparent as it could be.

“We need to try to explain to people that have these concerns that their city will be much more interesting than it was before,” says Escobar. “It’s inevitable that the cities will continue to densify. My hope is that we densify by increasing the quality of life and air.”

For now, Clausen plans to stay in Old Montreal. “We all enjoy history, the people who live here,” says Clausen, explaining that many of the old buildings repurposed into residential units had a completely different use in another era that contributed to the past of Montreal. “Each building has its own uniqueness.”