BY Hadassah Alencar

Ryan De Leon Clemente worked as a nurse for eight years before immigrating to Quebec in 2019. Like all internationally educated nurses (IEN), Clemente is undergoing a years-long certification process before entering a hospital, even as the province faces a nursing shortage exacerbated by the pandemic.

“There’s a lot of IEN nurses but the process is taking so much time,” says Clemente, who had to wait two years before beginning his recertification process.

As Quebec continues its efforts to attract more nurses from abroad to help fill needed jobs, Clemente warns the newcomers: “It is extremely challenging. You have to put in a lot of work and be patient.”

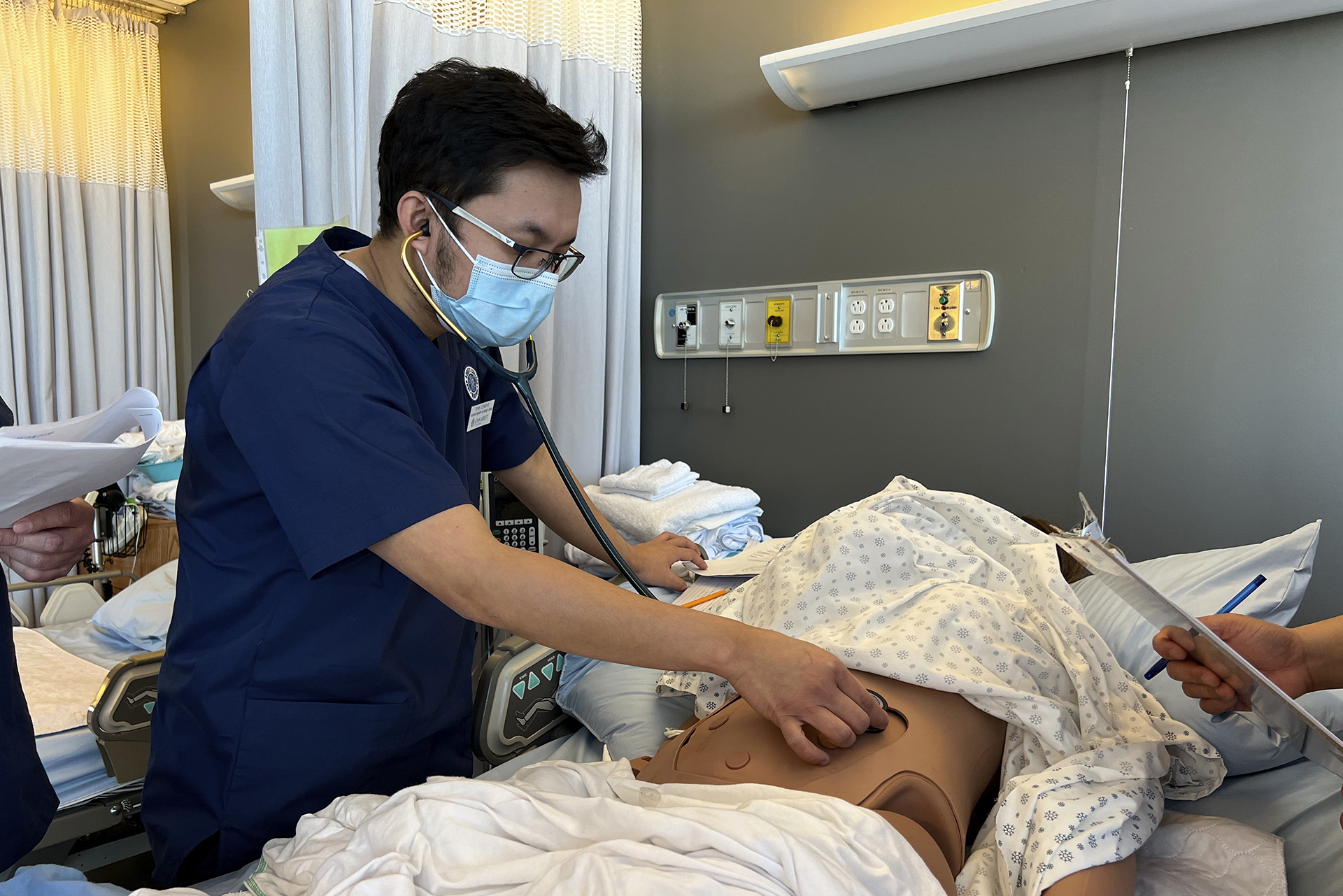

Ryan De Leon Clemente (second from left) during the team training portion of the Integration program at John Abbott College, where students perform tasks on medical manikins built for specific medical training exercises. Photo by Hadassah Alencar.

Last fall, the health ministry announced recruitment missions in France, Brazil, Belgium, Lebanon, and northern Africa in order to fill 4,000 empty nursing sector jobs. In December, Quebec committed $130 million to support better recruitment practices and integration of immigrants for high-demand jobs like nursing.

However, these campaigns are a long-term effort, even as thousands of nurses are leaving a pandemic-ravaged health sector due to burnout or illness.

The Professional Integration Nursing Program at John Abbott College is only a few months-long and can be a combination of or one of either CEGEP classes or studying by working in a clinical setting. Once candidates have completed their studies, they must pass their final nursing exams.

Immigrant nurses are lauded as heroes for their efforts to integrate into Quebec’s healthcare system in a time of need—however, they face multiple hurdles in their path to care for patients.

With limited spaces and strained resources, educators involved with the Integration Program for IEN nurses say they need more provincial support. Video by Hadassah Alencar.

Former nurse Evelyn Kaluga works for PINAY, a Montreal-based organization that advocates for Filipino migrant workers, as an organizer and full-time volunteer since 1995. She came to Canada in 1975 as an IEN and worked over two decades in the health force, but along with her other community tasks, she helps other striving IEN’s achieve their nursing status.

According to Kaluga, the province doesn’t address the barriers to nursing integration quickly enough.

“They need the nurses, they need healthcare workers in the hospital to help out, but I think the political will is not there to employ them,” says Kaluga.

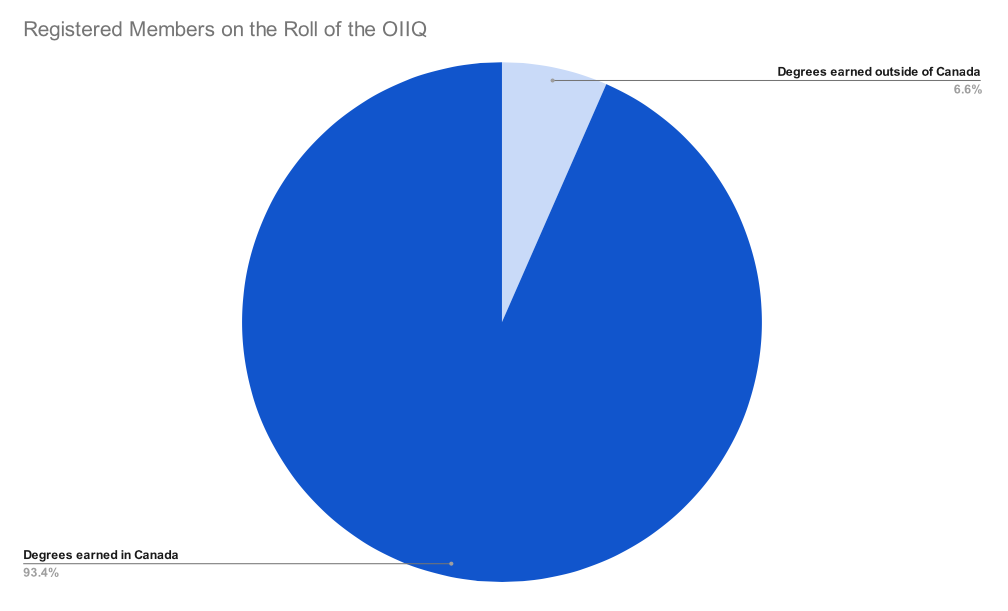

From 2011 to 2021 there has been a 57 per cent increase in Registered Nurses permits issued to those with degrees earned outside Quebec. Infographic by Hadassah Alencar.

In the province, there is the added challenge of a language barrier.

“There’s double jeopardy in Quebec because you have to have the requirements of French,” says Kaluga.

In order to be eligible for the Professional Integration into Nursing Program in Quebec, IENs must complete a mandatory certification level of French language proficiency in the intensive government-funded French language program.

When starting from scratch, the language program can last anywhere from four to 12 months. Quebec gives students $25 for each day they spend more than three hours in a course. That’s a maximum of $750 a month, which means some may need to study and work at the same time to afford basic expenses.

“They are put in a situation with focus on different things at the same time,” says Kaluga, who went to school full-time for seven months to learn French when she immigrated to Quebec. “We should provide some incentives so that they can survive while learning how to speak French fluently.”

However, even after an IEN achieves certification to work as a nurse, they are sometimes only offered jobs as caregivers, not in hospitals.

Kaluga shared an experience from a Filipino worker who left the province after only being offered a caregiver position.

“It’s very degrading to their self-esteem, their confidence,” says Kaluga. “In the Philippines, she was a clinical instructor and in the university […] She says ‘I want to go back home. I cannot continue working like this. You know, I have more knowledge than being a caregiver of a family.’”

Quebec is looking to increase Internationally educated nurses in hospitals, a group which currently accounts for less than 10 per cent of members registered on Roll of the OIIQ. Infographic by Hadassah Alencar.

A former ICU nurse with 16 years of experience, Bernard Berroya immigrated to Quebec from the Philippines as a skilled worker in 2018 to become a nurse in his field of practice.

But Berroya has spent years acquiring his certification and job hunting. Before being hired at a hospital ICU earlier this year, he worked at a long-term care clinic. He warns the newcomers: “If they cannot wait, don’t come here. But if you like challenges, if you like to study again from scratch, then come here.”

Elena Neiterman, lecturer at the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo and public health and nursing researcher, has studied how to build a more sustainable healthcare environment and remove barriers for IEN in the workforce.

According to Neiterman, the issue of IEN nurses being funneled into caregiver roles rather than into the nursing profession can be a form of discrimination.

“If you’re also looking at the segregation within the workplace, you often times see that international educated nurses will end up in long-term care facilities, or places that nobody wants to work where there’s maybe a lower pay, less of a job security or more work,” says Neiterman. “So they’re already kind of situated on a path where their career advancement is limited by where they allocated.”

Student nurses attend a lecture at John Abbott College. Photo by Hadassah Alencar.

These limitations also extend to cultural differences. In one interview conducted by Neiterman, a nurse shared that one of her questions during the mandatory examinations made reference to a jack-in-the-box. Since that toy was not popular in the nurse’s native country, she did not understand the question, and found it was unfair to her.

“For somebody who grew up in Canada, that makes total sense with jack-in-the-box, but for somebody who grew up in a different country, they may not know who that is, and it has nothing to do with nursing, “says Neiterman. “That is completely disregarding the fact that there are some people who may not have that cultural background.”

While the pandemic has brought challenges to the profession, it has also encouraged changes—in the future, Neiterman believes we should look at it as an opportunity.

“Maybe see whether or not what we’ve learned through the pandemic in terms of doing education in a different way, how we can leverage that and apply it so that we make it more seamless for people,” says Neiterman.

Clemente found new challenges when he began the weekly examination portion of the integration program. Since the program is divided into accelerated learning modules, nursing students must read several chapters a week to prepare for the tests.

Ryan De Leon Clemente (left) studies for a total of six months before being certified as a Registered Nurse in Quebec. Photo by Hadassah Alencar.

“The most important part in the integration nursing program is time management,” says Clemente.

While the program is difficult, Clemente is hopeful for his future and for the future of the nursing profession for other hopefuls in Quebec.

“Dedicate your time to studying—there is nothing impossible.”

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Ryan De Leon Clemente worked as a nurse in the Philippines for 10 years. It has been edited for accuracy. The City regrets the error.