BY Lillian Roy & Ana Lucia Londono Flores

In January 2020, Domenic Castelli had his next few gigs all laid out.

Soon, he would join Les Ballets Jazz de Montreal on tour as a stage technician. Then, during the summer, he would serve as the lead labour manager for a number of music festivals at Parc Jean Drapeau, including Osheaga and Heavy Montreal. Afterwards, he was off to work as a technician for an upcoming opera.

In March, however, Castelli’s plans came to an abrupt halt. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic brought Montreal’s live entertainment scene to a standstill, and Castelli was left jobless.

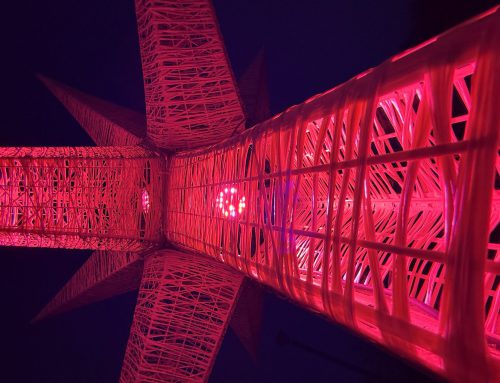

Music venues have faced long periods of closure throughout the pandemic. Photo by Lillian Roy.

“It’s a huge loss,” Castelli says, recounting his initial reaction to the news.

Between building sets, rigging lights, and chauffeuring bands around the city, Castelli is a regular ‘everything man’ when it comes to work in the live entertainment industry. Behind-the-scenes workers like Castelli are essential to producing live shows. Large events such as Osheaga can employ hundreds of these workers at a time.

A rigger helps set up a stage at Heavy Montreal, an annual music festival at Parc Jean Drapeau. Riggers are responsible for installing overhead apparatuses, such as lights. Photo courtesy of IATSE 56.

Although the pandemic caused him to lose his jobs, Castelli was able to stay afloat by selling his motorcycle and applying for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). Unfortunately, the same wasn’t true for all of his colleagues.

“A lot of people weren’t prepared for something like this,” Castelli says. “They were going hand to mouth.”

Castelli recalls how one member of his union sent money to another member to help him pay for food. The union also raised funds to help members who were struggling to pay rent.

Since stage workers like Castelli are considered to be independent contractors, they don’t receive the same benefits and protections that salaried workers do. As a result, the financial strain of COVID-19 has been especially difficult for them, and the issue is even further complicated for those who are non-unionized.

Natalie Goyer, President of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees Local 56 (IATSE 56), believes that stage employees should not be classified as independent contractors in the first place. The IATSE 56 is a union representing over 3,000 stage technicians, front of house workers, film technicians, camera operators, and hair, make-up, and wardrobe artists across Quebec.

A group of stage workers prepare the stage for Linkin Park and 30 Seconds to Mars’ Carnivores Tour at Parc Jean Drapeau in 2014. Photo courtesy of IATSE 56.

“A plumber, you call him and he’ll say ‘Okay, well, yeah I’ll be there in two days.’ He decides how much he charges you, all of that. He has his own tools, he decides how the job is done. We do none of that. We show up at work when we are told to show up at work, and we go on break when we are told to go on break, and we do the job we’re told to do—that’s not an independent contractor,” Goyer says.

According to Goyer, because of their status as being self-employed, most stagehands did not receive compensation for the termination of their contracts in early March.

“The link with your employer ends the minute you walk out of the theatre,” she said.

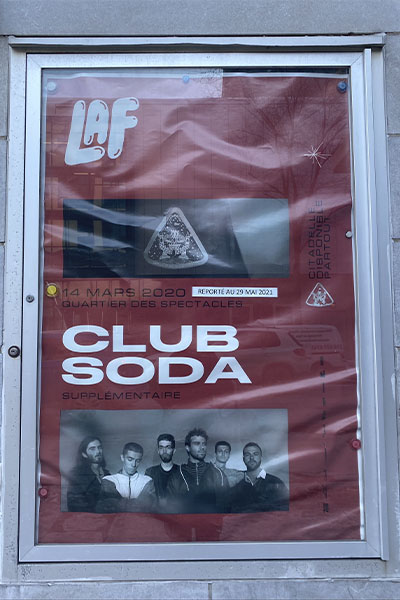

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a show at Club Soda was postponed from March 14, 2020 until May 29, 2021 and could be pushed back even further.

Some funds have been established to help support arts and culture throughout the pandemic, but behind-the-scenes workers are not always considered eligible for this aid. For example, in June 2020, the IATSE 56 requested that the Quebec government include stage workers in its $400 million fund to support the province’s cultural sector, but Goyer says she “certainly [has] not seen any impact” of this appeal.

“On the provincial level, we did not have […] communication. At all,” Goyer says.

Quebec says “the cultural recovery plan includes aid for all cultural sectors.” However, the current plan does not mention aid for independent contractors such as stage workers.

While Montreal’s live entertainment scene has undoubtedly slowed down, music studios are nearly fully operational. Video by Ana Lucia Londono Flores

Goyer speculates that stage workers have frequently been overlooked during the pandemic because their contributions to entertainment are seen as less valuable than those of the entertainers.

“We don’t seem to exist in this crisis,” Goyer says. “There is only talk about artists. I’m not saying they’re not suffering, but, you know, in terms of number[s], I suspect that for every artist there are three other workers that are not working right now.”

A look into the various responsibilities of stage workers during a show. Media by Lillian Roy.

As live entertainment doesn’t appear to be coming back in full force anytime soon, many stage workers have taken on jobs in other fields. According to Castelli, the nature of work in the gig economy means he and his colleagues are accustomed to a certain level of instability, and many have been able to adjust.

“We’re used to looking for new stuff. We adapt. You know, if it’s a snow storm we put on a jacket. If it’s raining, we’ll put an umbrella underneath it,” Castelli says.

Since the start of the pandemic, Castelli has busied himself by creating a book about the Jailhouse Rock Café, an iconic Montreal music venue. Today, he spends much of his time volunteering on a farm and is enrolled in a Concordia certificate course about labour law. He does not plan on returning backstage once the pandemic is over; instead, he’s saving up to buy a farm of his own.

“COVID, you can look at it in one of two ways: it sucks, or it’s a sign to do something else.”