Words: Carl Bindman

Photography: Julien Posnard

Avi Bendahan and Shijia Jiang are unlikely collaborators.

Jiang is an understated, classically trained performer of Beijing Opera, or Jingju, an ornate traditional Chinese theatre style. Bendahan is a boisterous local actor, dancer, and Concordia theatre graduate.

Find Bendahan on social media, however, and his name is @JingJew (he’s Jewish). He and Jiang together are the core of Jingju Canada, a multicultural theatre company that adapts the ancient Chinese art in Montreal and across Canada with a troupe of largely non-Chinese actors, directed by Jiang’s veteran hand.

“I really want people in the West to know Jingju,” says Jiang. “I want to show the audience so they can know what we’re doing.” The two are, in a sense, building an audience for the artform in and outside of the city’s Chinese community.

Getting into full makeup for male and female roles alike can take hours depending on complexity, and the elaborate costumes can take half an hour to get into.

Meng Rong, the executive director of the Confucius Institute in Quebec and described by Bendahan as the “patron saint” of Jingju Canada, says, “Beijing Opera is very strict, and hard to understand for contemporary people, young people.”

It’s a stylized, specialized form, with a heightened style of speech and singing.

“They don’t speak Mandarin, Standard Mandarin. No, they speak the Jingju dialect,” Rong says of the language used, which is comparable to Shakespearean speech. “You need to have special skills to understand.”

As a result, traditional Jingju’s popularity is fading in China. Internationally, it is less known than other Chinese cultural exports like Kung Fu. Bendahan notes there is also a certain skepticism from the Chinese community towards a majority non-Chinese Jingju troupe.

“We end up getting underestimated a lot,” he says. But he has found that doesn’t last through their performances, especially when people see what they can really do.

The costumes are sewn by hand in Beijing, and the bigger pieces can take up to one or two months to make.

So what do they really do? What is Jingju? Broadly put, it’s a musical theatre style developed in Beijing, the Chinese capital, that’s the result of thousands of years of theatre traditions. The rigid form of the art that attained its peak in popularity around 1930 dates back roughly 300 years.

Comedic and very physical, Jingju is like a meeting place of other Chinese arts: instruments, clothing, fighting, singing, acrobatics, makeup, and writing. It’s a medium of stock stories told with stock characters. The effectiveness of the work, traditionally, comes from how well those existing characteristics get executed on stage for an audience familiar with them. It’s like traditional ballet in that way. But as a confluence of many Chinese arts, non-Chinese audiences can sometimes struggle to understand what’s going on, even on a level as basic as setting. Bendahan points to one convention as an example of this problem: when characters move in a circle, it means they’re travelling a long distance.

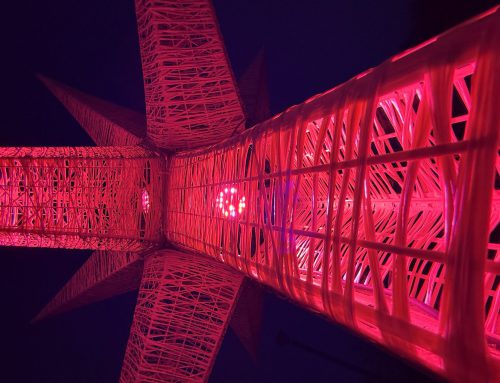

For the uninitiated, seeing Jingju performed in full makeup, full costume, and full sound is like falling into a kaleidoscope—it’s a spectacle, but it’s incomprehensible without the tools to decode what’s going on into meaning.

Bendahan is dressed as Shrimp, a character in The Monkey King Gets his Staff adapted and expanded from the Chinese folk epic Journey to the West.

Jingju Canada’s approach to that problem is twofold: translate and simplify.

Their first show as Jingju Canada was 2011’s Crossroads, a genre staple.

“It was the first time Jingju Canada translated a Chinese opera show into English,” says Bendahan. “And it was the first time we created new-ish characters.”

That’s a major departure in a genre where the same characters have been portrayed for hundreds of years. But, according to Rong, it makes sense to do so in a Canadian context, since some of the demands put upon actors by the stock characters are unrealistic for those who haven’t trained for years in that precise performance.

Rong points to singing as an example. “It’s not like singing a song, or singing opera. It’s high pitched,” she says. “It’s very difficult.” By adapting a work and removing the singing parts, they get to put their energy elsewhere.

Bendahan handles the translations. “The language is very hard for me,” says Jiang, referring to English. Jiang’s strong point in performance is combat—she trained in China as a wudan, a fighting woman. And by translating the text, they could add parts that let her do more of it.

“One of the largest scenes we created was for the character she played,” says Bendahan. “She played the wife of an innkeeper who has, like, two lines in the original play.” One of those lines was, “I killed them,” but the audience doesn’t see who, or why. “We were, like, ‘nobody in the west is going to understand that, so we need to put that scene into the play.’” And they did.

The daomadan, or general, displays the flags of her armies on her costume and sports a pair of long real pheasant feathers.

But change, of course, presents challenges.

“They don’t want to lose the core things from Jingju,” says Rong. That’s where Jiang’s other speciality, besides combat, comes in.

She was among the first in China to study the new-for-Jingju program of directing at the National Academy of Chinese Theatre Arts (NACTA) in Beijing.

“We learned new directing, but not only directing Beijing Opera.” she says. “We used music, dance, movies, to then put together with Jingju.”

She says her teachers pushed her to open her mind, to open up the art, to ask: if you put new things into Jingju, what would it look like?

It was at NACTA where she met Bendahan, when he was on exchange from Concordia—she was teaching the international students after graduating from directing. He and his peers wanted to do Jingju for their graduating show in 2010, and Jiang came to Canada to consult. A year later she was back with a work permit. They did Crossroads in 2011, and she has stayed since.

“Crossroads was very successful,” says Jiang. “The audiences really loved it.”

“The first one, when we did it, the prevalent sense was—we had decent sales the first couple of shows, but sold out the rest of the run,” Bendahan says. “Word of mouth just went like wildfire.”

Because the art form is so unique, sometimes audiences don’t know how to react. When Crossroads and The Monkey King Gets his Staff played at the Fringe Festival, they were nominated for awards in comedy, scenography, choreography, and more. They didn’t win a single one, though.

“No one knew how to classify us,” says Bendahan.

But still, they have performed at Fringe Festivals, at Chinese cultural events like New Year’s galas at Place des Arts, and have toured in Edmonton with their work—that was four years ago with the help of Rong and Edmonton’s Confucius Institute.

“I went to Edmonton in February and they were still talking about it,” says Rong.

After a hiatus following Monkey King in 2017—Jiang had a baby—Jiang performed at this year’s Chinese New Year Gala at Place des Arts on Feb. 9. Next, the troupe will be performing as part of Dawson College’s spring concert, organized by the Confucius Institute. They are also in talks with the Institute to put on a full show come October.

“I think for every culture, if the nice part can be shown to the public, and everybody understands and everybody enjoys, why don’t we do it?” says Rong. “So that’s why I like to support it.”