Olivier Laurin & Mina Collin

“The first thing that I was taken aback by was just how quiet it was,” says Katherine Vehar. “When you walk in the reading room, you’re met with high ceilings and stained-glass windows. It does feel a bit surreal.”

If Vehar’s description sounds like a church, you are not wrong. She’s talking about Concordia University’s Grey Nuns Reading Room — a repurposed chapel from the 151-year-old motherhouse of the Grey Nuns of Montreal.

The Grey Nuns Motherhouse was built in 1871 for the religious organization of The Sisters of Charity. In 2011, the location was designated as a National Historic Site. Photo by Olivier Laurin.

After buying the motherhouse for $18 million in 2007, Concordia completely renovated and repurposed the building.

The former religious institution now accommodates almost 600 beds in its residence section along with a cafeteria, 14 study rooms, and a reading room that can welcome 234 students.

This chapel is amongst one of several places of worship that have been repurposed on the island of Montreal. However, many more churches of the metropolis are facing an uncertain future.

The St-Bernardin-de-la-Sienne church, visible from Highway 40, was built in 1955. However, on January 27, 2019, the church caught fire and it was later declared a total loss. Three weeks later, the church was set ablaze a second time – with evidence suggesting that it was arson. Photo by Olivier Laurin.

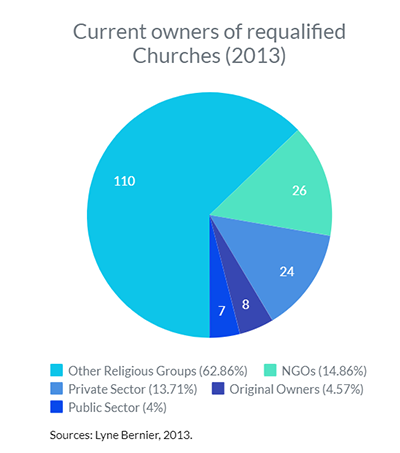

According to a 2013 report published in the magazine L’Action Nationale, 37 percent of Montreal’s 471 churches have closed, been sold, demolished, or transformed.

This pie chart identifies the distribution of owners of requalified Churches as of 2013 based on the numbers provided by Lyne Bernier in a report published in L’Action Nationale in June 2013. Media by Olivier Laurin.

For Luc Noppen, an architectural historian and professor in urban studies at UQAM, this is a worrisome trend. He is concerned that the disappearance of these places of worship might lead to an erasure of an important part of the city’s history.

“The Montreal church corpus represents the most important heritage on the island,” says Noppen. “Back then, entire communities would come together and build these churches. The rich had their possessions, and the people had their churches.”

Things changed with the advent of the Quiet Revolution in the 60s and a rapid decline in church attendance.

Additionally, Montreal was modernizing, means of transportation evolved, and the sense of communal attachment to physical places started to wither.

Montreal’s archdiocese — the governing body that oversees all Roman Catholic institutions on the island — is now stuck with too many churches.

“It is not easy to sell a church,” says Noppen. “The different municipalities and boroughs of Montreal have pretty much all defined their churches as part of their heritage. Therefore, it is harder than it looks to sell, demolish or modify these buildings.”

Potential buyers would likely need to go through a wide array of bureaucratic processes to acquire a church. There are numerous legal clauses and zoning laws that need to be respected before renovations can begin.

Located in Rosemont’s Little Italy, the St-Jean-de-la-Croix church was converted into a condominium complex by the firm Rachel Julien in 2002. Photo by Olivier Laurin.

There are three options available for the archdiocese to divest itself of a church. They can either sell to other religious groups, community organizations, or private entities. Noppen believes churches should be collectively owned.

“If we withdraw this religious factor, the church can remain at the service of its community,” he says. “We can have community organizations that use these existing buildings, already paid by the community, for the community.”

However, Noppen warns that it takes serious efforts to repurpose a church into a “container of public services”.

“To have a proper plan for a church, we need all actors—namely the municipality, the archbishop, the urban planners, the potential buyers, and the community, amongst others—to work collectively on achieving a common goal,” he says.

Heritage Montreal’s assistant policy director Taïka Baillargeon also believes that the city’s churches must be protected.

“Historically, churches played fundamental roles; they were the social core of the city’s numerous boroughs,” she says. “They would often play a greater role than their religious functions.”

According to Baillargeon, getting rid of churches would simply be unreasonable on many different levels.

“It is also a question of sustainability. We can not just demolish churches. Demolition and reconstruction are big pollutants,” says Baillargeon. “We need to be environmentally engaged in this effort to preserve our heritage.”

Baillargeon adds that many of these churches are in deplorable condition. They would require one or more costly renovations.

Ongoing major renovations on the St-Esprit-de-Rosemont’s main church steeple are preventing parishioners from frequenting their place of worship. The Conseil du Patrimoine religieux du Québec estimated the cost of the work at $2 million dollars. Photo by Olivier Laurin.

Baillargeon says that it’s up to communities to preserve their churches.

“The challenge resides in properly requalifying these buildings,” says Baillargeon. “If we want to preserve our churches, we must give them a second life. There is no one solution. We must be innovative. We should not limit ourselves.”

The great majority of Montreal’s churches are still used for religious purposes. Still, many also have their fair share of challenges.

The diocesan resource person for matters of religious patrimony Caroline Tanguay explains that churches usually manage to pay their daily expenses. But they can run into trouble if they need major repairs.

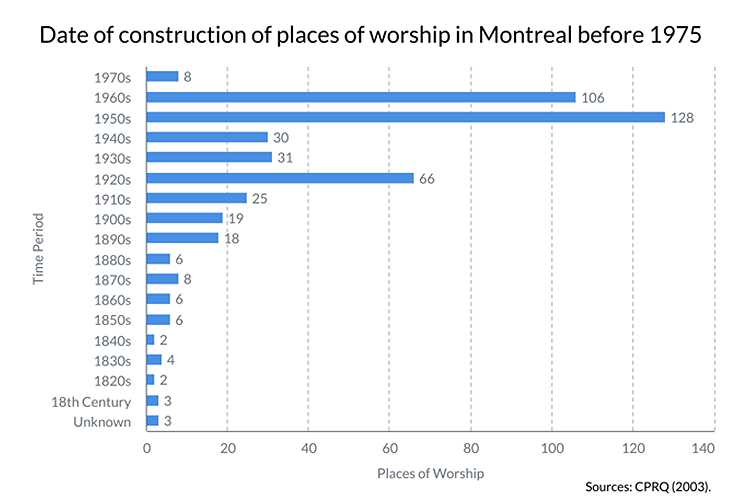

“There were two big waves of church-building in Montreal. One in the early 20th century and the other in the 60s,” says Tanguay. “The materials used in the older churches are currently reaching the end of their life. It is the same for the 60s’ churches that used more recent materials with a shorter lifespan.”

This bar chart identifies the date of construction of places of worship in Montreal before 1975 based on the numbers provided by the Chaire de recherche du Canada en Patrimoine Urbain UQAM in a 2011 report. Media by Olivier Laurin.

The major work needed in many churches would require hundreds of thousands of dollars apiece. Even with $20 million from the province to protect religious heritage in 2021, it is only a fraction of the church’s financial needs.

Founded in 1912, the St-François-Solano church, located in Rosemont, is but a shadow of its former self, now covered in graffiti. Currently belonging to the federation of the Seventh Day Adventist Church, the building has been left unused since the beginning of the pandemic. Photo by Olivier Laurin.

Many places of worship survive by relying on the help of volunteers. However, this lifeline might not last for long. This volunteer workforce is aging rapidly, and churches are facing a decline in volunteer involvement.

While religion is less and less prevalent in Montreal, the community of St-Jean-Vianney church is doing everything in its power to keep their institution alive. Video by Mina Collin.

For his part, Priest Patrice Bergeron is all-to-aware of the current condition of religion in the metropolis.

“I do believe that we have too many churches in Montreal for the number of disciples we have,” he says. “We would have had to pay around a million dollars to fix one of our church’s steeples. All that for what? To keep a church open for 40 churchgoers on Sundays? Instead, we want to put our money and effort in churches where we see a future.”

Rosemont’s Notre-Dame-Du-Foyer church is currently closed due to public health safety concerns regarding one of its steeples that requires major renovation.

Photo by Olivier Laurin.

Although Noppen, Baillargeon, and Bergeron all have a different relation to the churches of Montreal, their opinions all converge to one point: the doors of the city’s churches must stay open to the public.