BY Melissa Migueis & Olivier Paiement

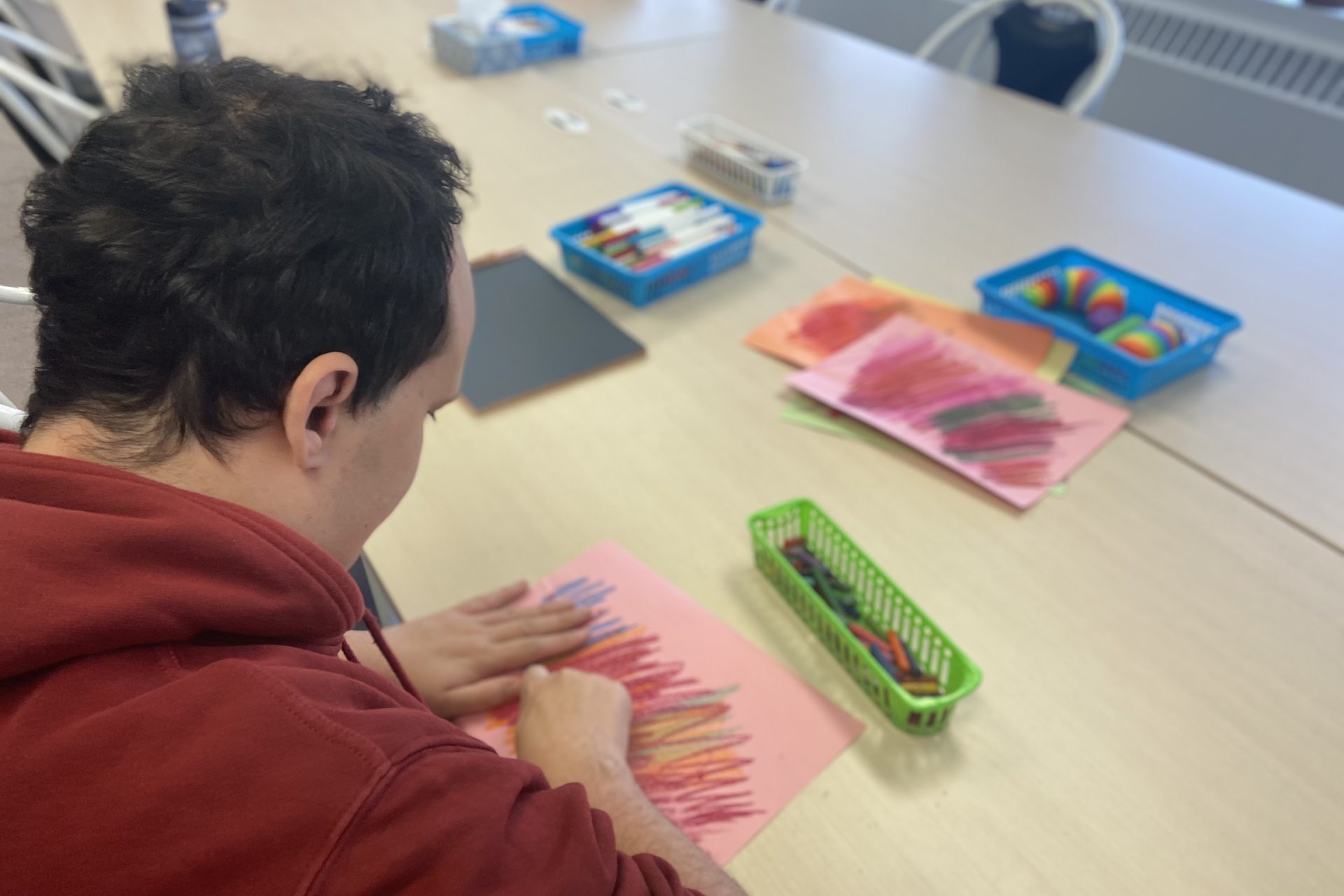

Italo Ferrante, 25, sits in the colourful creativity room at the Center for the Arts in Human Development.

The Centre offers a three-year program that employs creative arts therapies – including art, dance, drama and music therapy – for adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities.

Posted on the walls surrounding Ferrante are photographs of past theatre productions and artwork. Clay, pastels, paint and other art supplies sit on a small table beside him.

Feeling anxious after a stressful past few days, Ferrante sits breathing heavily looking at the blank sheet of paper.

He picks up a blue pencil crayon and begins to draw.

“I’m just trying to stay calm,” he says.

Ferrante, an adult on the autism spectrum, has been attending the Center for the Arts in Human Development for two years.

“I really really really love this program,” says Ferrante. “I have really seen myself come from a person that is very anxious to a person that is getting way calmer.”

Italo Ferrante draws in the creativity room at the Centre for the Arts in Human Development. Photo by Melissa Migueis.

The Centre for the Arts in Human Development supports creative expression and fosters a sense of community for neurodivergent adults.

The Centre was created in 1996 specifically for adults due to a lack of therapeutic services available to support this population at the time.

Nearly 30 years later, the same issue persists.

In Quebec, children with neurodevelopmental disabilities, like autism spectrum disorder, stay in school until the age of 21. Once they age out of the youth system, most are faced with a tough reality: services and resources are limited, waitlists are lengthy and private programs are costly.

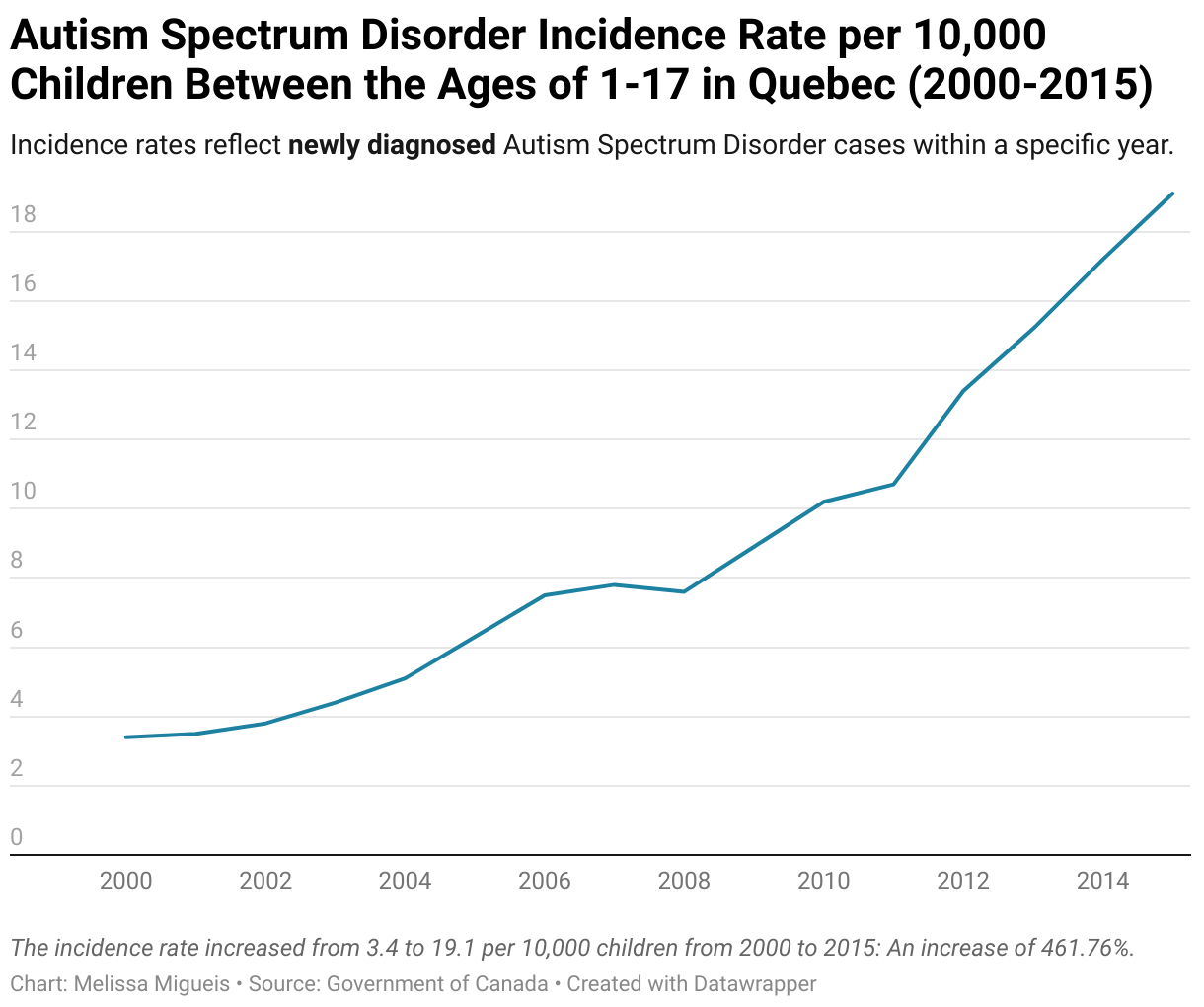

From the year 2000 to 2015, the number of individuals between the ages of one and 17 diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder increased by 461.76 per cent, according to a report by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

However, services aren’t increasing, says Elisabeth Prass, the provincial Liberal party critic for autism-related issues.

“It’s the chicken and the egg,” says Prass. “It’s great to diagnose them and the government is taking all of that into account, but if you’re not increasing your services to serve that population, what’s the point?”

“[It’s] definitely a huge problem in Quebec,” she adds.

The incidence rate increased from 3.4 to 19.1 per 10,000 from the year 2000 to 2015: An increase of 461.76 per cent. Media by Melissa Migueis.

According to Prass, there are almost no government arts-based resources and services for adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities.

“The older you get, the less public services there are,” she says.

Prass says the onus is on the immediate family and community organizations to take on the responsibility of creating programs for this population.

Audrey Burt – mother to non-verbal autistic son Keyan Saha – understands this reality all too well.

Burt noticed her son was responding well to music therapy, but the therapeutic service was private, out-of-pocket and costly – averaging approximately $90 an hour.

To ensure that others could have the same opportunity to access this kind of therapy, despite their financial situation, Burt founded S.Au.S – a community organization on the South Shore of Montreal offering programs and services to children, teens and adults on the autism spectrum.

Music therapy was the first program implemented at the Centre.

Jonathan Simard, an autistic adult, plays the tamborines with support worker Sabrina Harvan during music time at S.Au.S. Photo by Melissa Migueis.

The community organization has grown to provide multiple other therapeutic and recreational services, such as soccer, swimming and fitness, since its inception in 2009.

Burt explains that providing recreational sports at S.Au.S is important. This is because, similar to the barriers she experienced accessing creative arts therapies, finding leisure activities that were adapted to her son’s needs was extremely challenging.

Community organization Power Buddies brings adapted activities to neurodivergent adults in Montreal. Video by Olivier Paiement.

Burt is frustrated with the government’s lack of programs for young neurodivergent adults.

“Nothing really makes sense when you look at it,” she says. “The people who need help are not getting help. The people who need help are the ones that are doing the work.”

According to the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux, the government provides services and support for people with disabilities. But the services listed in government documents don’t impress Burt.

“I call them phantom services,” she says. “Nobody’s getting them.”

Spaces in these organizations – which are few and far between – are limited and waitlists can be years long, Burt explains.

“So, even when you find a service, it’s step one of actually being able to access it,” she says. “It’s disgusting. The government is not stepping up. They’re not meeting the needs. That’s for sure.”

According to Prass, there needs to be more programs integrated into the healthcare system, including creative arts therapy programs.

“I think there needs to be a greater recognition within government that therapy for people who are neurodivergent doesn’t just come in speech therapy or occupational therapy,” she says. “It comes in music therapy. It comes in art therapy.”

And the benefits of these therapies are clear, according to Vosberg.

Autistic adult Laurent Beauchamp high-fives support worker Cassandra Gagnon after completing an art activity at S.Au.S. Photo by Melissa Migueis.

Back at the Centre for the Arts in Human Development, the effectiveness of creative arts therapies has been proven – both through practical evidence and in research.

Vosberg says that the participants show improvement in self-esteem, social skills and autonomy over the course of the program.

“We see, in many people, transformations in how they feel about themselves,” she says.

In 2008, the Centre for the Arts in Human Development was designated a university-based research centre. It has since contributed immensely to the field of creative arts therapies, scientifically proving their effectiveness for those with neurodevelopmental disorders, explains Vosberg.

According to art therapist Maria Riccardi, every individual will react differently to creative arts therapies, but in general, these therapies can help with relaxation, feelings of accomplishment and learning how to breathe.

They can be especially amazing for those with neurodevelopmental disabilities who may not have the words to express themselves, she says.

Ferrante is one of the few who is getting the chance to experience these benefits firsthand.

Italo Ferrante draws using pencil crayons and pastels at the Centre for the Arts in Human Development. Photo by Melissa Migueis.

“We can fully express ourselves and not walk on eggshells, and not worry about what everyone else is going to think or say,” Ferrante explains.

Ferrante hopes that all neurodivergent people will be able to try creative arts therapies easily in the future.

“We have every right to do what we want to do and try everything like everyone else does. Period,” Ferrante says. “We are humans. We are worth it.”