BY Myrialine Catule & Laura Bolanos

As soon as it was proposed to her, specialized nurse practitioner Fanny David volunteered to receive training in medical assistance in dying (MAID).

“It’s like another addition to the work I already do,” she says.

It’s only been a year since David started working for the oncology palliative care clinic located at Hospital Cité-de-la-Santé where they receive patients diagnosed with stage four cancer. Throughout the year, she became more familiar with MAID.

“I found it interesting to discuss it, also assess the patient’s aptitude and criteria to facilitate the coordination of care, [then] have the request signed,” she says.

Fanny David is busy working on her computer in her consulting office at the Hospital Cité-de-la-Santé. Photo by Myrialine Catule.

A specialized nurse practitioner has been able to provide MAID and continuous palliative sedation as of December 2023. They are also permitted to complete the death certificate and generate an attestation of death.

In 2023, 5,211 people received MAID, which is more than any other province. That number is expected to increase by nearly 15 per cent in 2024.

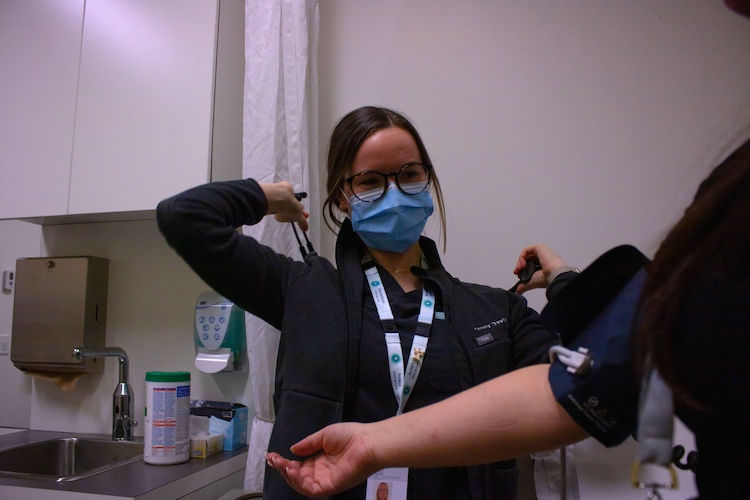

Fanny David is preparing herself to practice numerous tests on one of her patients. . Photo by Myrialine Catule.

David has undertaken training on the administration of MAID. That way, she is guaranteed to be present for her patients right until the end.

“I found it interesting to get involved in this since I was already involved in this specialty and I know very well how to carry out the process,” says David.

Yet, David admits that she felt apprehension before witnessing someone being released from their suffering for the first time even though she was used to seeing people dying in her unit.

Sometimes, nurses will experience anxiousness beforehand since they want their patient’s last moments to be perfect, and feel sadness right after the act, according to David Lavoie, a psychotherapist from the University of Montreal Hospital (CHUM).

“I’ve seen more anxiety in the air and there’s that kind of moment of silence [because] we know that it’s happening on the unit right now,” he says. “A couple of minutes after we see the pharmacy out of the room, then we see the nurse going out and go behind the desk, cry a bit, and then talk to [their colleagues].”

However, nurses who decide to take part in MAID are at peace with their decision, explains Lavoie. They are psychologically prepared to offer this service and agree to do it.

Different types of nurses play different roles when it comes to the time to respond to an MAID request. Starting the moment they receive a request, to the evaluation, then the coordination, followed by the administration of the lethal injection, says Lavoie. According to him, nurses can rely on each other to find support.

Veronique Fraser encountered many cases in her career that have been emotionally challenging. However, she finds her job as an advanced practice nurse for medical aid in dying at the McGill University Health Center (MUHC) very rewarding.

“I think in general I feel that my job is to honor and comfort the wishes of sort of autonomous, capable adults to choose how they want to live and how they want to die,” says Fraser.

She received approximately 300 MAID requests over three years. Each time, the experience is unique for those who are accepted.

“It’s still a time of immense grief, but it’s helping people sort of hold that grief and sort of provide the death that people want,” she says referring to the family present in the room.

Both nurses admit that every case of MAID goes differently since each procedure will be crafted to match the desires and the vision of the person.

“I’ve had people who wanted to be completely alone. I’ve had people in a room with 30 people. I’ve had people who wanted it to be a party. […] I’ve had some people where it’s much more sad,” says Fraser.

She had to learn how to establish a professional distance and set limits on her emotional attachment towards her patients to avoid being too implicated emotionally in every MAID case. It’s similar to mechanisms developed by palliative care nurses to overcome grief.

A palliative care nurse’s experience dealing with grief and loss. Video by Laura Bolanos.

“We got involved because we were ready and no one is forcing us to provide this care. We do it because we want to offer it,” says Christine Laliberté, president of the Association of Specialized Practitioner Nurses of Quebec.

According to Laliberté, patients and their families feel more comfortable when the same nurse can be present throughout the whole care because of the relationship and trust established.

However, she highlights “the importance of respecting our own limits.”

When nurses do not feel comfortable proceeding with an MAID case or are reevaluating their position, they have the right to use their conscious objection to refuse to participate. Some nurses do take advantage of this privilege.

Catherine Perron is working for the ethics department at the Hospital Cité-de-la-Santé. Last year, she submitted a report to the government with recommendations on how to improve Interdisciplinary Support Groups in Quebec. Photo by Myrialine Catule.

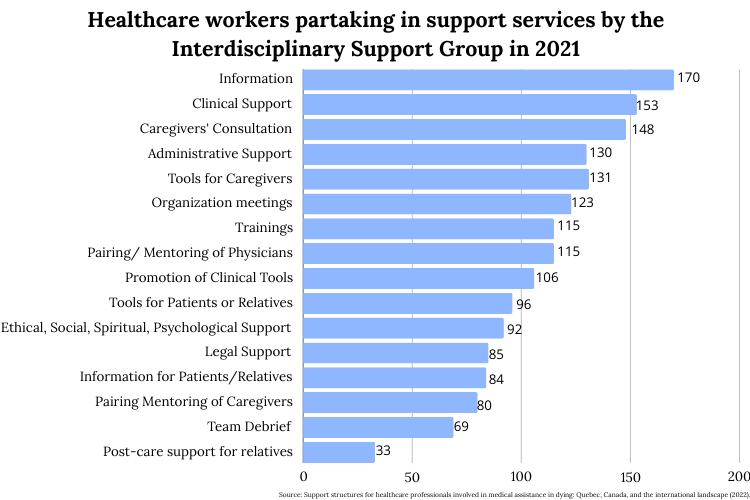

When MAID was legalized, the province invited medical institutions to establish an Interdisciplinary Support Group to assist healthcare workers.

“When there are administrative, clinical, legal, and ethical issues, healthcare workers can turn to ISG to say ‘Ah! What do I do in this situation?’” says Catherine Perron, an ethicist at the Laval CISSS. “Concerning anything related to MAID, the ISG is there to support them.” says Perron.

Nearly 30 ISGs have been registered and each group is composed of members from diverse specialties and milieus to provide the best pieces of advice.

According to Perron, every ISG helps at least 50 nurses each year related to training, information, administration, clinical or emotional support. Their role is to accommodate the various needs of healthcare professionals.

Healthcare workers partaking in support services by the Interdisciplinary Support Group in 2021. Infographic by Myrialine Catule.

Many medical institutions are implementing other programs to support the mental health of their employees.

For example, the psychology department at CHUM started an initiative called Adapte-COVID to provide psychological support to their peers during the pandemic, which has been revamped into Parlons-en. Now, employees can approach them to talk about any issues.

Fraser, whose role is to help build and support MAID service at the MUHC, carries out multiple strategies to support nurses.

“After each MAID, we offer a debrief with the team so that everybody can talk,” she says. “Not technical stuff, but like, what are they feeling? What are the emotions? How do they need to process them?”

They can even have access to spiritual care support if they prefer. Her ultimate goal is to prevent anyone from experiencing emotional isolation.

Fanny David is walking in the hallway of the oncology palliative care clinic located at the Hospital Cité-de-la-Santé. Photo by Myrialine Catule.

Therefore, nurses appear to rely a lot on relational coping. The first MAID case attended by David, the doctor who presided over the operation took the time to check on her before, during, and after, to make sure she was alright throughout the whole process.

“A lot of the time just being there is enough,” says Lavoie.