BY Mélanie Lussier & Kaity Brady

In January 2023, 28-year-old Esteban Crespo put a $1,000 deposit on an electric car which, according to his dealership, should arrive by the end of the year.

“I knew I wanted to buy a car, so I started reading about the myths and realities surrounding electric vehicles,” Crespo says.

There are persisting misconceptions and uncertainties surrounding the reliability, the long-term costs, and the environmental footprint of electric cars. As a result, buyers are left to weigh the options on their own.

“I figured the best choice was to buy an EV over a gas-powered car, so I started looking at models that I liked the most aesthetically,” Crespo says. “I narrowed down my selection to five options, and consulted The Car Guide and several websites to compare the specs: the autonomy, which accessories already come with the car and for what price, etc. I had a top two, but after calling multiple dealerships, I only found one place where I could test-drive one of these cars.”

Ultimately, it took Crespo three months of research and reflection before he settled on a customized IONIQ 5, which was priced at $60,000. As of February 2023, this model was also the 19th most popular electric car in Quebec.

As of Feb. 2023, the Car Guide identified the Tesla Model 3 as the most popular electric car in Quebec. Photo by Mélanie Lussier.

“With the IONIQ 5, we attract a lot of high-end car owners, clients who usually have Lexus, Mercedes, BMWs, and Audis,” says Christina Nulli, car sales representative at Hyundai Longueuil.

Crespo acknowledges that it is his financial situation and circumstances that allow him to make such a purchase. He has no children, and has been working full-time for the federal government for almost two years, mostly working from home, earning $70,000 a year while living with his parents.

According to the Quebec EV Association, the average EV owner is 46 years old, male (87 per cent of all owners in 2019), with a median annual salary between $70,000 and $80,000.

“Electric car buyers are often tech-savvy, gadget loving clients,” says Nulli. “In many cases, they are customers who change cars very quickly. For example, I have a client who took possession of his IONIQ 5 in February, and he’s already on the waiting list for the next IONIQ 5.”

“Clients may say they want to reduce their ecological footprint, but what I’m seeing are buyers who like their toys,” she adds.

However, Daniel Breton, President and CEO at Electric Mobility Canada (EMC), rejects the idea that electric vehicles are only accessible for the wealthy and those always looking to get their hands on the latest technology.

“Today, if you buy an entry-level electric car, it will cost you less than a new entry-level compact gasoline car,” he says.

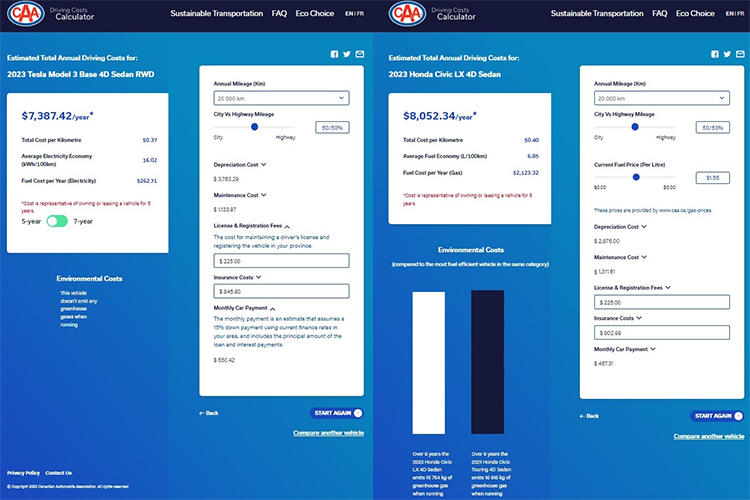

Combined screen captures of CAA’s Driving Costs Calculator, comparing a 2023 Tesla Model 3 Based 4D Sedan RWD to a 2023 Honda Civic LX 4D Sedan. Capture by Mélanie Lussier.

If we compare a 2023 Honda Civic LX 4D Sedan to a 2023 Tesla Model 3 Based 4D Sedan RWD using the CAA Driving Costs Calculator, we can see that the base model of a high-end luxury EV brand is now cheaper than the fairly popular affordable gas powered car.

According to George Iny, Director of the Automobile Protection Association (APA), electric cars are currently affordable thanks to the generous amount of government incentives.

“People in the EV space are buying up,” he says. “The manufacturers who made the more rational, smaller, less expensive cars have less interest in those. The ones that are selling well are super vehicles.”

But even in that category, Iny adds, heavy subsidies in Quebec have made it so that a basic Tesla can be bought for less than a comparable gasoline car.

Table illustrating the estimated affordability of gas, electric and hybrid cars. Table by Mélanie Lussier.

However, the reality is that being able to pay for an electric car, doesn’t necessarily equate to being able to afford to have one.

For example, a construction worker who must travel 600 to 900 km to get to work sites would not necessarily be able to find the time and place to recharge their vehicle. And Northern Quebec is currently a black hole for charging according to Hydro-Quebec’s Electric Circuit interactive map.

Breton himself recognises that charging infrastructures aren’t ready everywhere, although he says he is confident that objectives will be met at the rate things are going.

“The challenge is going to be in city centers where we have to install charging stations for people who don’t have access to charging at home,” he says.

Experts warn Quebec is still a long way off from having the resources and infrastructure needed to support the mass adoption of zero-emission vehicles. Video by Kaity Brady.

Another accessibility concern is that most electric cars are not recommended for towing. “Installing a trailer hitch on an EV can void the manufacturer’s warranty,” explains Nulli. So from a practical standpoint, buying an EV may not be in everyone’s best interest if they can’t use it the way they need.

If EVs are affordable, then why are there incentives?

In December 2022, the Government of Canada made its first move to enforce its EV mandate announced in June 2021 requiring that all new passenger vehicles and light trucks sold in Canada after 2035 be electric zero-emission vehicles. Regulations will be gradually phased in, starting with the imposition of a 20 per cent sales target in 2026.

Since June 2022, the Quebec government has also tightened its goal with a plan to have 1.6 million electric vehicles – or about 30 per cent of all light vehicles – on the roads by 2030.

Our governments’ sales targets might impact economic activities such as taxi-driving. Photo by Mélanie Lussier.

To achieve this goal and make electric vehicles more accessible, the provincial government is taking action on two fronts: supply and demand.

Enforced in 2018, the zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) standard compels automakers to sell a certain number of ZEVs on the Quebec market, or face penalties.

“[This] norm currently is not restrictive enough, it is known, so we are working on a new draft to reinforce it and supply the market,” says Valérie Savard, Director of the Residential and Transportation sectors for the Climate and Energy Transition Office of the Quebec environment ministry.

But sales and production are not what Concordia University Economics Professor Moshe Lander is worried about, especially given how much time markets will have to adapt until 2035.

“Technology will advance fast enough that the production side will probably not be the issue,” he says. “It all comes down to ‘if I’m going to have to buy a new car, and you are removing my choice to buy a gasoline car, then you’ve got to make sure that I will not experience bottlenecks elsewhere [with an EV], such as where I can charge it, how to store it and how far I can go with it.’”

It can take between 12 minutes and 8 hours to charge an EV, HydroQuebec indicates on its website. Photo by Mélanie Lussier.

When it comes to city infrastructure, Lander says he is skeptical that urban design is going to adapt fast enough to accommodate government targets.

In Montreal, the city is encouraging businesses to participate in the development of the public charging station network.

“[We are doing so] notably by increasing the financial assistance offered by the provincial and federal governments, and through new regulatory provisions,” says Karla Duval, Public Relations officer for the city of Montreal. “The City of Montreal will also invest $42.5 million between 2021 and 2025 to double its fleet of public charging stations to 2,000.”

For Lander, this “magic number” doesn’t seem to be enough, but beyond the quantity issue, is also the matter of space.

“The way the charging stations are designed right now, is that they are put on the streets. There are some pillars that have [two] plugs that can extend to your car. Those cars are going to be [charging] there for hours. So now you are taking parking space on the road, and you are creating congestion on the streets,” he says.

“It’s not enough that you just have to come up with more charging stations; you need to come up with a way that those charging stations can be put in a place like a parking garage.”

This is what EMC President and CEO Breton suggested to the city of Montreal when he brought up the idea of ‘charging hubs.’

“You take a parking lot, and you install 20-30-40-50 charging stations instead of installing one station here and there. That way, it becomes much easier for people to find a place to recharge their vehicle.”

The charging stations that we can find along street parking in urban centers are Level 2 stations. Charging usually takes two to three hours. Photo by Mélanie Lussier.

Quebec has been working on an electric vehicle charging strategy, as announced in its 2030 Plan for a Green Economy. Savard, who works at Quebec’s environment ministry, says Quebecers can expect an official document to be published in the coming months.

On the demand side, the provincial government launched the Roulez Vert program in 2012 to “encourage the acquisition of new and used electric vehicles and the installation of charging stations,” and to compensate for the higher upfront purchase cost of electric vehicles, according to the website.

With the $7,000 provincial rebate and the $5,000 federal rebate on the purchase of a rechargeable electric or hybrid vehicle, on top of the $600 provincial rebate on the purchase of a home charging station, Hyundai St-Basil’s $3,000 “new graduate” rebate, and an additional $1,400 in miscellaneous discounts, Crespo will be able to save $17,000 on his brand new EV.

According to Lander, the problem isn’t that higher income people can more easily afford electric cars—after all, it is the same for all new technologies and material goods. He says that the bigger issue is that the subsidies disproportionately benefit the wealthy.

“If high-income people are more likely to be willing to spend, to either flaunt their environmental credentials or because they have the disposable income to put their money where their mouth is about their environmental credentials, then offering them a subsidy is just essentially stuffing money into their pockets,” he says.

The Roulez Vert program is in fact funded by the carbon market, which ultimately affects all consumers of fossil fuel byproducts. For Lander, EV buyers are basically being subsidized by drivers who cannot yet afford an EV.

“There was a desire on the part of the [provincial] government to refocus the program on the middle class,” Savard says. That’s why, as of April 1, 2020, EV rebates could only apply if the manufacturer’s suggested retail price is below $60,000.

However, on April 18, 2023, the threshold was raised to $65,000. Savard indicates that changes like these are made to reflect the market.

At the federal level, the government launched the Incentives for Zero-Emission Vehicles Program (iZEV) in May 2019. The $5,000 rebate can currently be applied on cars up to a maximum Manufacturer’s Suggested Retail Price of $70,000. Photo by Mélanie Lussier.

Raising concern over the long-term implications and potential changes to policies and regulations that may affect their affordability in the future, Iny, Director of the APA, also notes that it is important to be transparent with consumers about the fact that the benefits of driving an electric car may not last forever.

As more people switch to electric vehicles and there are fewer gas-powered cars on the road, there may be a decrease in gas tax revenue, which is often used to fund road maintenance and infrastructure.

He suggests that, to make up for the loss in revenue, we could see a price increase in vehicle registration fees.

“EV drivers will have to realize that they won’t be driving for free forever,” he says.

According to Iny, rebates for EV owners are exaggerated compared to efforts that are being put into other sectors.

“I don’t think anyone ever thought of giving $12,000 to a person so they would take the bus,” he says. “It’s such an expensive way, and an inefficient way, to migrate people out of gasoline vehicles.”

Driving the green agenda

Whether or not government targets are met, Breton deplores the fact that Quebec’s fight against climate change and transportation electrification strategy are so focused on zero emission light road vehicles.

“A lot of people think that all I want to do is sell electric cars,” he says. “But I’ve been saying it for decades: the fleet of vehicles must be reduced. We must encourage car-sharing, car-pooling, public transportation, active transportation, and heavy-electric transportation.”

“We need a sustainable transportation cocktail,” he concludes.

Nicolas Chevalier, Organizer with Climate Justice Montreal, agrees that we need to get out of fossil fuels, but points out that an EV mandate is only one measure out of many.

On Sept. 23, 2022 thousands of students and workers marched for climate and social justice in Montréal and other cities across Québec. Photo by Mélanie Lussier.

“Zero-emission vehicles brand [this mandate] as something that is clean, that is good for the environment, and a tool for fighting climate change,” says Chevalier. “But the reality is, unfortunately, not as rosy. Canada continues to exploit the tar sands, and natural gas… They are simply offsetting this in a net-zero type policy.”

Chevalier says that, with our province’s and country’s interests in lithium mining, our governments have all the more reason to want the EV market to expand.

They add that, from a climate justice perspective, a just implementation of Quebec and Canada’s EV sales mandates simply does not exist.

On his end, first-time EV buyer Esteban Crespo says he wanted to own an EV for financial and practical reasons: to save on gas and maintenance, and benefit from privileged access to reserved lanes and parking spaces.

He did not mention environmental concerns as a criterion that might have guided his decision.

“I needed a car, and I knew that the government would demand it at some point,” he says.