BY Lana Brady & Sandrine Blanchette

Even as the world re-opened after the pandemic, Audrey Mercado-Brünger and their partner, Tristan Brünger, were still worried about leaving their house. Not for personal health reasons, but for the mental health of their dog, Fergus.

“We can’t anticipate it. It’s just one day he’ll be super anxious, and we’ll just have to adjust how we leave him,” says Brünger.

Ferguson, a five-year old doodle, on his owner’s bed waiting to play. Photo by Lana Brady.

Fergus is a five-year-old golden doodle, and was only a year old when pandemic regulations forced him inside for 23 hours a day.

By the age of one, Ferguson was considered a well-trained dog with a playful attitude. Wanting to do it right, Mercado-Brünger and Brünger spent a lot of time and energy training him.

“He would never really bark,” explains Mercado-Brünger. “He was completely kennel trained. He liked the kennel. It was his little safe haven.”

However, after the pandemic, Fergus went from being in constant company to being left alone for long periods. He started showing signs of anxiety to the point where he had to be put on anxiety medication.

Liam Pantis, a canine behaviourist and trainer, says a dog’s behaviour can regress if owners do not continue training throughout a dog’s adolescence.

“Sometimes people see training as a one-and-done sort of affair. You train a dog to sit and then five years later they’ll remember how to sit when in reality that’s really not the case,” Pantis explains. “If dogs don’t have the occasion to practice behaviour, it won’t be inherited completely into their thought process or their memory bank.”

During the pandemic, Fergus and his owners, like many families, spent most of their days in isolation without any training situations. Fergus is one of many dogs that developed behavioural issues from the experience.

Ferguson looks out of a window with one of his owners Audrey Mercado-Brünger. Photo by Lana Brady.

In Canada, around 10 per cent of people purchased, adopted or fostered a new cat or dog during the pandemic, according to a 2021 survey.

Pantis says the pandemic affected each dog differently depending on their age and maturity. For dogs between one and a half and three and a half years old, every interaction with their owner reinforces or punishes certain behaviours. As the number of interactions increased between owners and their dogs during isolation, dogs learned how to get positive reinforcements from their owners who sought out their dogs for comfort.

“[The dogs] developed more positive associations with being around people during the day,” says Pantis. “If a dog really likes being around its people during the day and they go back to work in an office, then, the dog is likely to experience high levels of stress.”

On the other hand, puppies born during the pandemic, commonly referred to as COVID puppies, did not learn to properly socialize and to “speak dog” which led to its own set of problems in behaviour.

“Later down the line at four or five years old, [COVID puppies] could get into fights with other dogs because they don’t know how to respect boundaries. They don’t know how to read boundaries. They don’t know how to communicate their own boundaries with other dogs,” says Pantis.

Furthermore, COVID puppies never learned how to be alone which is an important aspect of their early behavioural development. They grew only to know the company of their owner.

“Now during the pandemic, we had nowhere to go. So, there was no real reason to teach a dog to be alone, and that’s the main reason for young dogs coming out of the pandemic [to develop] separation anxiety,” explains Pantis.

Graham Smith, a dog trainer and behaviourist with Bark Busters, says the behavioural issues of post-pandemic dogs can include separation anxiety, general anxiety, leash reactivity, excessive barking, etc. In some cases of anxiety, the dog will stop eating and will cry and bark while the owners are away.

Whether a first-time or veteran dog owner, the pandemic put them in unprecedented waters with the care and training of their dogs.

“Because people had a lot of time, that was when you read a book or you looked at a YouTube video or a TikTok video on how to train dogs, there’s a thousand different ways. And so, people ended up basically skipping from one to another, to another, to another,” explains Smith. “That inconsistency, if you like, could have a detrimental effect.”

Seeing the changes in their dogs, owners realized the intensity of caring for a pet. These behavioural issues can take a toll on pet owners.

“It was hard, it still is hard. I hate not being able to feel completely relaxed all day, every day. [Plus], having a baby. It’s hard to train yourself not to yell his name when he’s barking because you don’t want your kid to do the same thing,” explains Mercado-Brünger, a new mother to a 5-month-old boy.

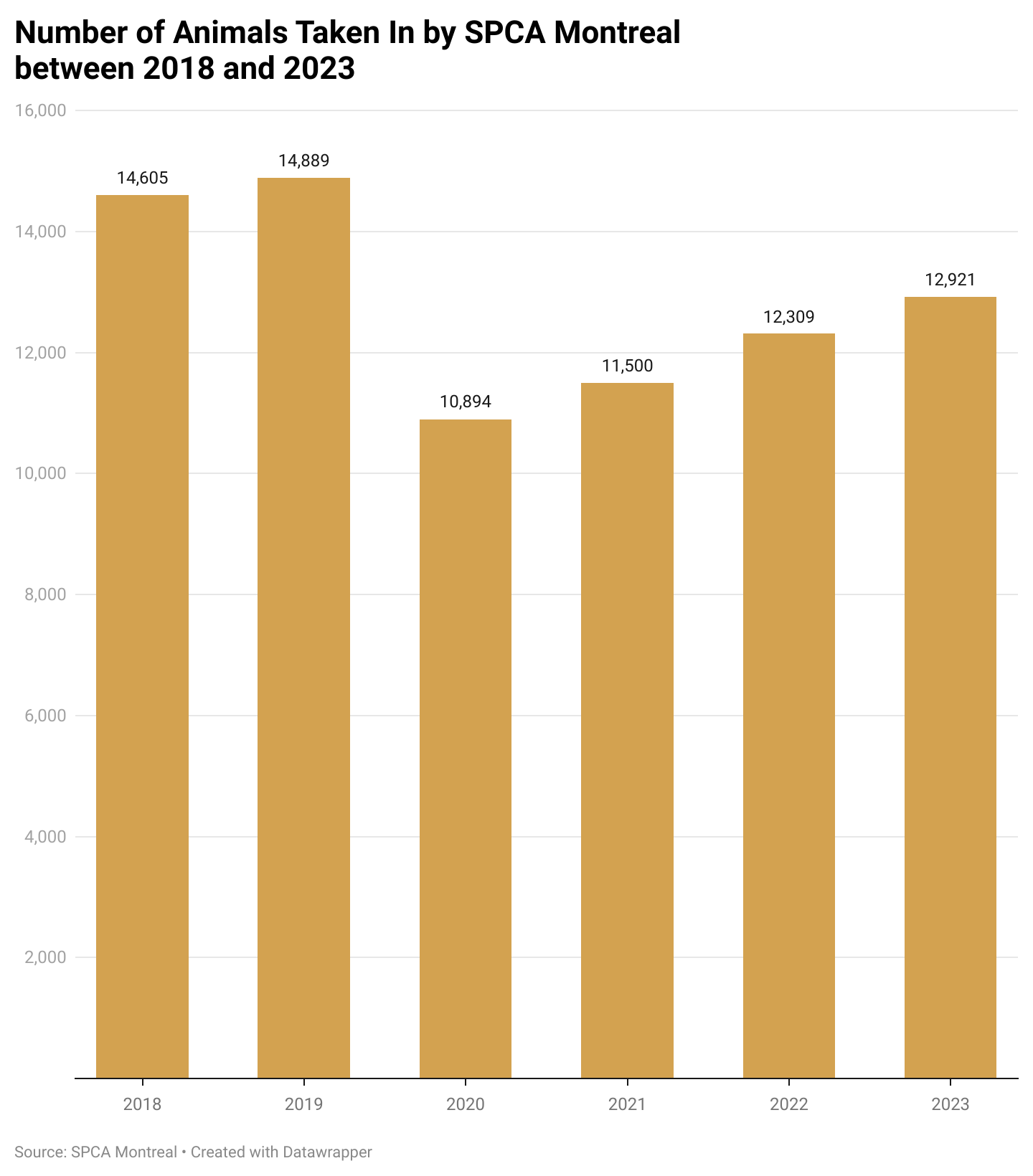

As the world returned to normal routines in 2021, shelters saw a rise in pet abandonments as owners struggled with post-pandemic realities like behavioural issues. Though the numbers have not reached pre-pandemic animal intakes, the SPCA, already affected by post-pandemic financial and personnel shortages, is feeling the effects of the rise in numbers.

This graph shows the number of animals taken in by the SPCA between 2018 and 2023, according to their annual reports. Media by Lana Brady.

“When the pandemic happened, it was the perfect timing to get an animal. People were always at home. They [had] the time and the energy to take care of the animal, but as soon as the pandemic was over, well, people wanted to go back to work, back to travel and everything. So, it wasn’t perfect anymore,” says Laurence Massé, the general director of SPCA Montreal.

According to Massé, in 2023, the Montreal SPCA received almost 13,000 animals, which is stretching their resources. They saw an increase of 10 per cent in surrenders from 2022.

Cats have not escaped the anxiety that comes from a change in routine after the pandemic. What does a cat’s post-pandemic life look like? Video by Sandrine Blanchett.

Behavioural issues are only one of the many reasons for dog surrenders. In 2023, Massé says many surrenders were related to financial and lifestyle issues, including the rise of living costs and newborns, which made owning a dog even harder.

However, some owners are being forced to surrender their dogs because of circumstances out of their control.

Penny, a newly surrendered dog, poses for a photo for her adoption profile with Passion for Paws, a Montreal-based dog rehoming program. Photo by Lana Brady.

Olivia Doublos, founder of Passion for Paws, a dog rehoming program in Montreal, says the decision to get rid of a pet is not an easy one for many owners.

“A lot of them get emotional,” explains Doublos. “I would say 90 per cent of the families never wanted this and never envisioned it. It’s always an impossible circumstance that they’ve usually tried to solve. It just didn’t end up working out.”

To prevent another wave of surrenders, some experts and owners are advising future dog owners to educate themselves on the time, cost and lifestyle adjustments necessary to care for a dog.

“If you’re going to adopt a dog, especially a doodle or some breeds that are usually anxious, really think hard about that. […] I wish I’d done more research about it,” says Brünger. “If another global pandemic occurs, maybe don’t adopt a dog during it.”

However, dog behaviourists believe that all behavioural issues can be fixed — it’s just a matter of time and patience.

“Every dog has the capacity and has the potential to get better. The question is whether people are willing to give the time and the energy it takes to develop that transformation,” says Pantis.

Brünger and Mercado-Brünger use home remedies to soothe Fergus, such as playing music. Lo-fi beats continuously playing on their TV, indestructible toys to keep him occupied, and a monitor that allows them to soothe Fergus’s crying and barking from a distance.

“Sometimes, he just needs to hear our voice,” explains Mercado-Brünger on their routine when they leave the house.

Audrey Mercado-Brünger holds her dog Ferguson’s paw in their living room. Photo by Lana Brady.

However, for Mercado-Brünger and Brünger, rehoming Fergus is not an option that they have ever seriously considered. Even with a newborn, they have developed a system that works for them. Though taxing, Fergus will continue to be a part of their family as long as it is in his best interest.

“It’s just his quirks. He’s a good dog. It’s just he needs love and extra attention like we all do,” says Mercado-Brünger.