BY Maria Cholakova

Every morning at 9 a.m., David Sherber walks to his closest depanneur and buys a newspaper. At 60 years old, he says the tradition has stuck with him.

“Since I was 20, I have always read through the print, my morning wouldn’t be complete without it,” he says.

Although Sherber tries to buy a physical copy every morning, he says it is becoming harder to find them with each passing year.

“Even before the pandemic, I had slowly started realizing that some stores had stopped selling [newspaper] copies, and I had to hunt them down,” he says.

Sherbet isn’t the only one experiencing this. According to Statistics Canada, print circulation continued its decline, falling 24.8 per cent between 2014 and 2022.

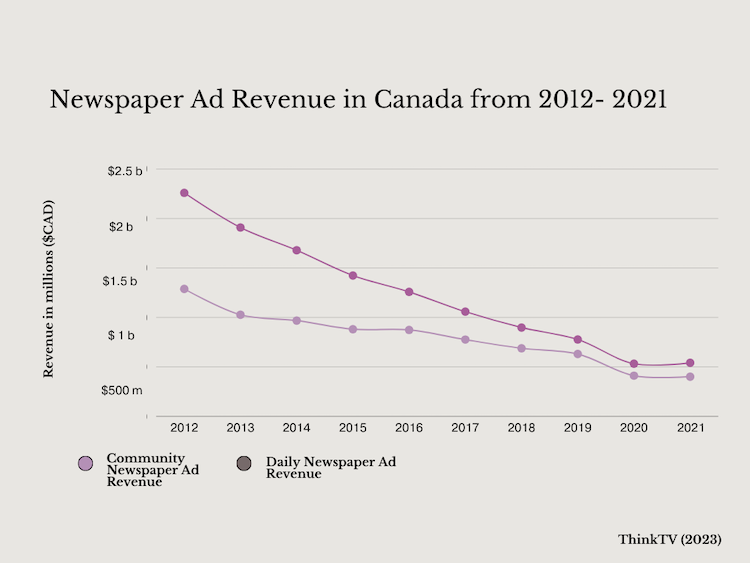

Newspaper ad revenue in Canada from 2012-2023. Graphic by Maria Cholakova.

“It is really sad to see papers being less popular nowadays,” Sherbet says, “But I wish I didn’t have to see it with my own eyes. I know that there is a digital format for news, but I don’t think it can ever compare.”

“Advertisers have stopped buying ad space because they themselves are overwhelmed,” says George Guzmas, co-publisher of the Parc-Extention News. “They do not have personnel and do not want to spend money on ads.”

Guzman also blames the provincial and federal government for its reduction in ads sold to local newspapers.

“In the early 2000s the government was advertising in the local newspapers, and then […] decided to switch to Facebook and Google, which became a big burden for local newspapers,” he explains.

According to News Media Canada, an association of newspaper publishers, the federal government bought $513,000 worth of print ads in 2014. By 2019, that was down to $4,000.

Guzman describes the government’s decisions to reduce ad revenue as an infringement of free speech.

“The government has to look in the mirror and realize what they have done to local newspapers. Because without [us], there is no actual democracy,” he says. “Every time a newspaper folds, we restrict democracy and credible news to the community.”

Local newspapers like Parc-Extension News are not fighting alone.

The Quebec Community Newspaper Association opened its doors in 1980 and helped support the expansion of English newspapers in news deserts. In addition, it played the middleman for distributing ads between the government and local papers.

“I would say that ads were our bread and butter, but now, due to several factors, that isn’t the case,” says Ikra De Laat, QCNA’s General Manager.

Scattered copies of The Link newspaper. Photo Maria Cholakova.

English newspapers have faced additional difficulty following the passage of Quebec’s latest language law, Bill 96.

“In 2019, there was a lot of advocacy work, to try and remind the provincial and federal government that small newspaper communities need the advertising revenue to survive. But it all fell on deaf ears,” she says. “Then the pandemic hit. And there was a brief lifeline with the [provisional government] advertising that helped our newspapers survive the pandemic. However, after the pandemic [ended] and [with] Bill 96, the province-wide advertisers or national advertisers are no longer interested in any smaller English language market.”

The QCNA is also working on supporting local English newspapers through different initiatives and federal grants like the Local Journalism Initiative (LJI).

Through the LJI, they distributed $5.1 million dollars to 21 newspapers over two years.

“We try to ensure that civic journalism was being created for the underserved communities because we’re a minority language [and a] minority culture, in the province,” De Laat says.

In addition to the LJI funding, QCNA works on strengthening its connection to its members and tries to help out in any way possible.

However, even with QCNA’s different avenues to help, some things are out of their hands.

“Sometimes our newsrooms are too small to actually have staff on board. More and more journalists are working part-time and freelance. Newspapers are finding it harder to find good reporters. Our newspapers can’t really afford the salary considering the cost of living these days that a professional, even a new graduate, requires to have a decent standard of living,” De Laat says.

“Only one newspaper, The Senior Times, closed its doors, but we have a few new [ones] who joined. It’s nice to see people joining, as showing that their communities care for them,” she says.

One of the newly added QCNA members is The Link newspaper. The independent student-run newspaper switched to a magazine in 2017 but switched back to its original newspaper format in 2022.

Zachary Fortier, the Editor-in-chief of The Link, says the shift to newspaper was hard but necessary.

“Existing as a magazine, which published one a month and in some cases, published one every three months, our visibility was incredibly low. We needed a boost of readership and a bi-weekly newspaper print edition would achieve that, through its frequency, quality and impact on stores,” says Fortier.

An unopened stack of newspapers. Photo by Maria Cholakova.

Switching back to print has been challenging, according to Fortier, and a lot of work due to it costing significantly more than the magazine.

“Printing isn’t cheap, it costs upwards of $30,000 a year, but it was an investment in our presence on campus, instead of it being a smart financial decision,” he says.

Like other papers, The Link is also struggling with funding. According to Fortier, The Link in the 90s used to make more than $100,000 in revenue, just from ads. Now, that number has decreased to $15,000.

“The amount of revenue that we have lost due to the complete shutdown of ads, due to digitalization, has significantly impacted how much staff we have at the paper,” he says.

Fortier emphasized that The Link is still fighting to stay afloat. Because of the pandemic, The Link stopped physically printing and had saved thousands of dollars, which were then reinvested into the paper’s post-pandemic issues.

A student reads The Link newspaper. Photo Maria Cholakova.

Even through the paper’s troubles, its readers can’t imagine the Concordia campus without it. According to Nadia Alipanahi, a student at Concordia, reading The Link every two weeks has become part of her routine.

“I have a stack of every print the newspaper has done this year, can’t imagine what I would read if they weren’t publishing,” she says.