BY Sasha Teman

“Caracol gives people the chance to start over and rebuild their lives and their futures,” says Yasin Jama, a 31-year-old web developer who has been living in a Paris apartment complex since September 2020.

Collocations Caracol was founded in 2018 with one goal in mind: To create links between culturally diverse residents in shared, affordable housing. Based in Toulouse, France, Caracol aims to match refugees with French locals, accelerating their integration in the job market and in French society.

“The goal of shared apartments is to help create links between residents coming from all walks of life,” says Elisa Desque, development manager at Caracol.

Prior to his arrival in France in November 2016, Jama had lived in several different countries including Ghana, China, and the UAE.

Web-developer Yasin Jama prepares a cup of tea in the shared dining area of the Rousseau apartment in Paris’s 1st arrondissement. Photo by Sasha Teman.

When he first arrived, Jama moved from one reception centre to another all over Paris. But he longed to share an apartment with a Parisian. His aim was to learn the language and culture of his new country.

“My ultimate goal was to be surrounded and integrated with the French people” he says.

The concept of flat sharing is nothing new to him. However, Caracol’s diversity and inclusion mandate factor certainly was.

“I finally didn’t have to go out of my way to find the locals, because this time I was living with them,” he says.

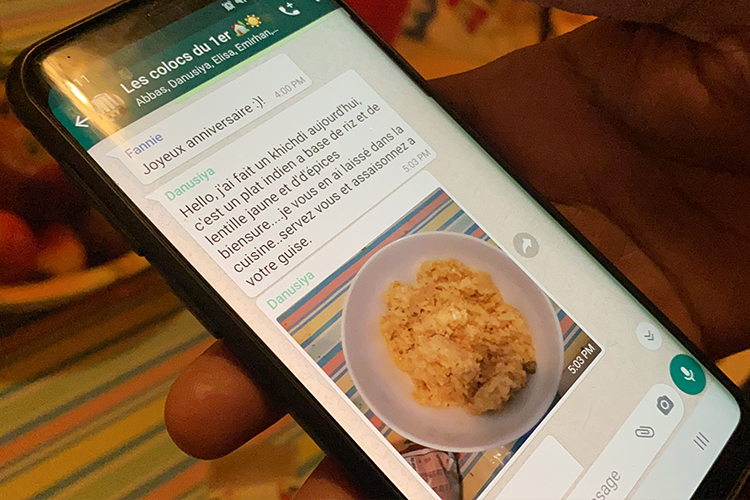

A WhatsApp group chat for the 25 tenants living in the Rousseau apartment allows for a variety of activities such as cooking workshops and shared meals. Photo by Sasha Teman.

Paris has been dealing with a housing crisis for the past decade, which has caused many low-income workers to flee to the suburbs. Between 2012 and 2017, over 11,000 residents relocated from Paris to surrounding suburbs each year.

According to the 2020 Worldwide Cost of Living Survey, Paris is among the top five most expensive cities to live in.

The share of Parisian residents described as working class has declined from 35 per cent in 1999 to 26 per cent in 2020. This demonstrates a stark contrast to the 51% of the total labor force that the working class represents nationally. Some experts fear that with France being in its deepest recession since WWII, the French capital may no longer remain a place where ordinary people can afford to live.

The cost of living has skyrocketed 66 per cent in the last decade, with the cost of a one-bedroom apartment averaging $1,463 a month (975 Euros). The Parisian housing market lies on the upper end of the spectrum, making it increasingly difficult for French locals to find affordable housing.

“[Caracol] came to life in an effort to resolve two problems that were fairly easy to identify: For one, many people have a difficult time finding affordable housing in Paris,” says Simon Guibert, the co-founder of Caracol. “However, these types of difficulties are taken to a higher degree when it comes to individuals who have just obtained or are in the process of obtaining refugee status.”

Caracol develops low-rent housing units in vacant lots throughout Paris. Tenants are only asked to provide a monthly payment of €190, or 30 per cent of their income for the duration of their stay.. The aim is to facilitate the transition to a stable form of housing for refugees, whose administrative status frequently impedes them from finding apartments in Paris.

A map of the various Caracol low-rent housing units and attractions nearby. Map by Sasha Teman.

A recent report conducted for the French National Assembly found that few people leave temporary housing, suggesting that it is challenging for refugees to find permanent homes.

In accordance with Caracol’s rules, new tenants can stay for 12 months but can extend that by six months if they’re looking for permanent housing. For those escaping the dangerous living conditions in their home countries, Caracol simplifies the transition process between conventional accommodation and regular accommodation in Paris.

Nearly 18,000 refugees are in the national reception system, including 5,000 in the emergency accommodation system. However, the number of asylum seekers eligible for accommodation is greater than the number of places available to shelter them. At least 90,000 asylum seekers were not accommodated in 2020 alone.

French Housing Crisis prompts call for more action for incoming refugees. Video by Sasha Teman.

Caracol intends to change that narrative for good. Providing refugees and local young people with the means for a shared apartment, establishes a sense of security and inclusion.

“At Caracol, we strive to bridge the gap between accommodation style housing and long-term accommodation to improve the living conditions for residents seeking asylum and better opportunities,” says Guibert.

Upon arriving in Paris, Jama was desperate. “I had no money and no financial means to pay rent for an apartment, form of housing, I was unable to be considered as an employee because of my social status but I also wanted to work, earn money and provide my family with some money because that’s what we’re told to do,” says Jama, who fled Somalia.

Caracol accommodates a small percentage of the French refugee population able to seek effective housing solutions. Out of the 50 residents currently living at various Caracol flatshares in France, only 25 have obtained refugee status.

“For the moment we’re a very small complementary solution,” says Guibert. “Obviously our main goal is to grow exponentially but we will give ourselves the proper amount of time for that,” he adds.

“Above all, Caracol’s aim is to promote in any way possible the emergence of other structures that offer habitat through temporary occupation,” says Guibert. “There are more than enough empty buildings for everyone and in fact the impact will be multiplied if we manage to transmit good practices that have already proven to work.”

These places are unoccupied for various reasons.

“Eight per cent of buildings in Paris are empty, accounting for one in ten apartments of real estate vacancies,” he says.

Caracol’s most recent housing projects helped bring a formerly vacant building to life. Located in the heart of Paris’ 1st arrondissement, the Rousseau project debuted in September 2020, becoming the new home of a diverse group of twenty-seven roommates. It’s located just five minutes from the Louvre museum in one of the city’s most chic neighborhoods.

Tenants of the Rousseau apartment, located in Paris’s 1st district, pose for a picture in the place that they are now able to call home. Photo courtesy of Simon Guibert.

For the past two years, Caracol has worked with Unity Cube, a non-profit organization founded in 2016 by architecture and engineering students.The organization initially aimed to discover how to quickly occupy office spaces and replace them with a means of temporary accommodation.

According to Capucine Velay, project manager at Unity Cube, it was a match made in heaven. ’“We had their backs when they were first getting started, because we had that technical aspect that they were lacking at the start,” says Velay.

“The city became involved because they’re always looking for ways to provide monetary donations as a form of social support, and in the case of Caracol, a social housing initiative unlike any other,” Velay says.

Borough councillor of Paris’s 1st arrondissement, Ariel Weil, attended the Rousseau apartment’s inaugural party.

“Because it is an innovative housing project, it is also a part of the city’s policy to promote social housing in the heart of Paris,” says Velay.

As Caracol continues to expand to other French cities like Toulouse and Strasbourg, Guibert feels confident that the initiative he helped put together three years ago has facilitated the transition from accommodation style housing to permanent housing in France.

Jama currently works as a web developer and volunteers part-time to lend a helping hand to incoming refugees who are currently in the same situation that he was once in several years ago.

He says that without Caracol’s assistance, he most likely would not have been able to do half the things he has accomplished.

“Caracol gives us an entry way that would otherwise be much more difficult to obtain otherwise, especially in a country like France,” says Jama. “I live with some great people and I’m really happy. I have a stable job, a great group of friends, whom I see regularly and go out to grab a bite with, we have great discussions about everything that’s going on in the world, I can’t complain.”

A multiple-choice quiz based on information provided in the article. Media by Sasha Teman.