BY Olivia Johnson & Luca Caruso-Moro

Leo Parent spoke with a stutter as a child. He had a difficult time pronouncing every second or third word.

“I remember that I got in trouble for not answering [the principal] fast enough, so she was yelling ‘spit it out god damn you,’” he explains. “And I didn’t think anything of it at the time, because when you’re young you go with the flow, you learn how to survive. Those days forced me to learn how to adapt how I speak—to not say certain words. I began to become creative with my speech out of fear.”

A guidance counselor at the Kahnawake survival school, Parent attended the Kanesatake Six Nations Hereditary Federal School from grades one to six. He is one of the many Indigenous children who attended Indian Day School across Canada from the late 1800s and into the late 1980s. He registered when the settlement was announced and will now apply for compensation.

“I just felt a little guilty,” Parent said about applying for compensation. “I’ll be honest. I guess because at that time it was just so normal. It was normalized,” says Parent. “You know abuse isn’t always just bruises. It’s emotional scars.”

Despite his experience with the principal, Parent says he did have loving and caring elementary teachers.

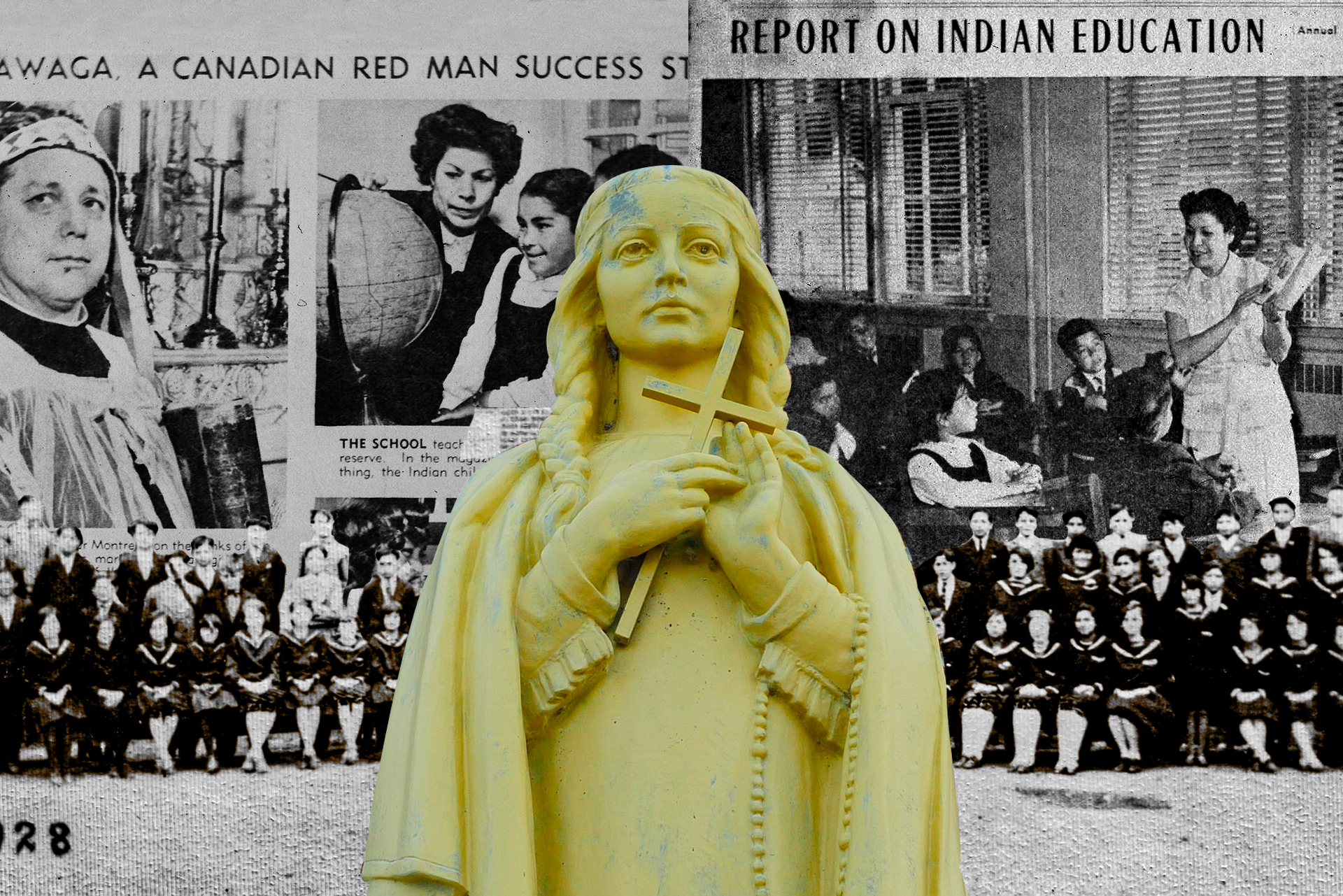

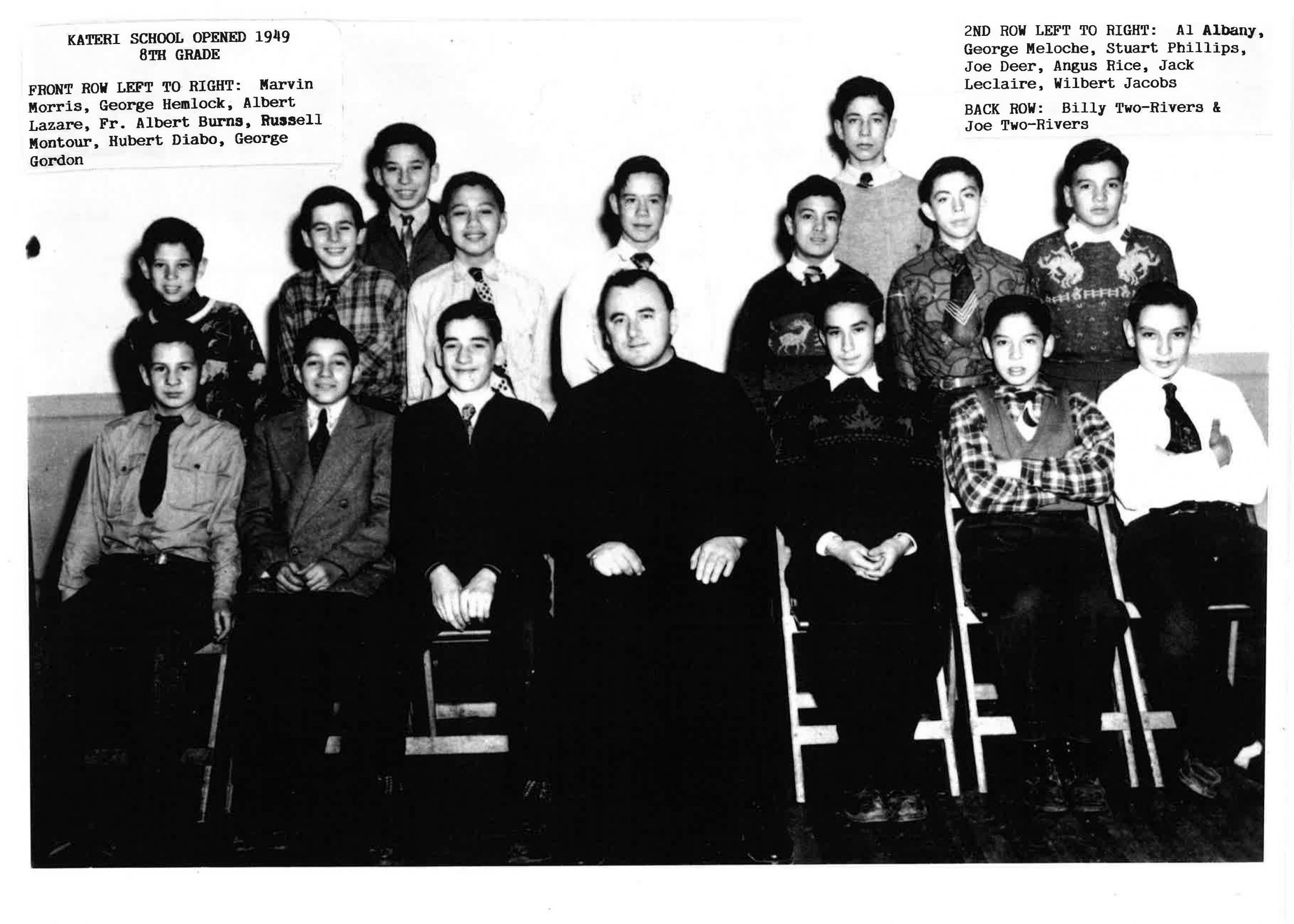

The first ever class of Kateri School, one of eleven Indian Day Schools in Kahnawake. Photo courtesy of Kateri School. Photo by Luca Caruso-Moro.

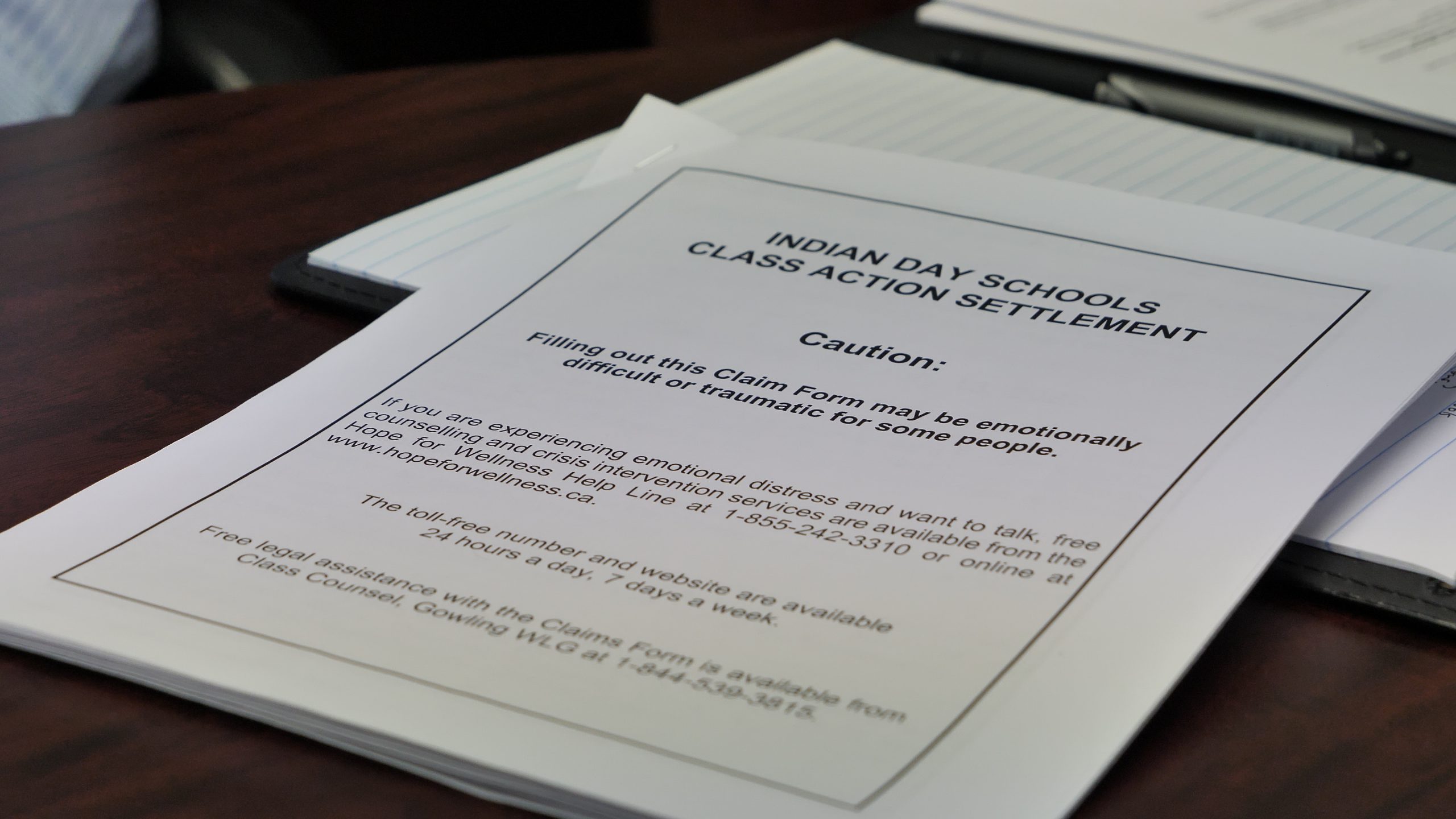

On January 13, 2020, the Indian Day School Settlement Claims Process was officially opened.

Survivors who “suffered harms while attending Federal Indian Day Schools and Federal Day Schools” can now apply for a minimum $10,000 in compensation, as well as an additional $50,000 to $200,000, depending on the severity of the abuse.

There are five classes of compensation for eligible survivors ranging from $10,000 and $200,000. The level one class refers to verbal and physical abuse and the level five class provides compensation for survivors of repeated sexual or physical abuse causing permanent or long-term injury.

Additional support will be provided to families and communities can also claim compensation from a $200 million Legacy Fund. The fund is meant to support commemoration projects, health and wellness programs, truth-telling events, and the restoration and preservation of Indigenous languages and culture.

An Indian Day School compensation form features a disclaimer in bold on the front cover warning applicants of difficult questions inside. Photo by Luca Caruso-Moro.

It is estimated that close to 200,000 Indigenous children, including First Nations, Inuit, Métis and Non-Status, attended one of the 699 federally-operated Indian Day Schools in Canada.

“I think most of the public is familiar with Indian Residential school or boarding school,” says Wahéhshon Shiann Whitebean, “The Indian Day School was founded under the same premise, which was to anglicize, assimilate, and colonize Indigenous people by targeting their children.”

An Educational Research Assistant at Kahnawà:ke Education Center, Whitebean is researching the impact of Indian Day Schools that existed within her community.

“For Indian Day Schools, the major difference is that children went to school either within their communities or close by for the day and usually returned at the end of the day to their family,” she says. “So, it was the same sort of structure, usually run by missionaries or the clergy, and funded most often by the government or federal funding. A lot of similarities, but clearly children in day schools had the benefit of being in contact with their family members.

Whitebean is Kanienʼkehá꞉ka and grew up in an oral tradition and culture. Being surrounded by her grandparents, great-grandparents and even her great-great-grandmother as well as her aunts and uncles, she was raised hearing stories of Indian Day Schools.

“I knew a lot about the day schools and some of my family members told me experiences they had, but when I got to university there was little information about day schools,” she says. “I’m thankful people are talking about residential schools and that research is being done and the silence is being broken, but there was very little information on the Day Schools.”

There were 11 Indian Day schools in Kahnawake, on the south shore of the Saint Lawrence River, near Montreal.

Whitebean attended Kateri school, which opened in 1969. The school was transferred from the Federal Indian Day Schools administration to Kahnawake in 1988. It is one of two that is now being run by the Kahnawake education center.

There were a total of 11 Indian Day Schools in found throughout Kahnawake. Media by Olivia Johnson.

Whitebean is legally eligible to make a claim but says she has mixed feelings about doing so, as she was taught by community, or Indigenous teachers. Whitebean is not the only person who has struggled with deciding whether or not to apply for compensation.

“Some people that I talked with when I did my research said that they didn’t realize they went to Kateri school and that it was a day school,” she says. “I would be working with my grandmother and they said, ‘Oh, but she didn’t go to day school, she went to Kateri school.’ And I said, ‘Kateri school was an Indian day school.’”

Tekahentahkhwa Stacey leads a Mohawk class for Kindergarteners with an Awé:ri (heart) craft. Video by Luca Caruso-Moro.

There have been mixed reactions to the day school compensation from the people of Kahnawake. Whitebean explains that for some it’s a form of justice, while others see it as “blood money.” Some people are still coming to terms with the fact that they went to Indian Day School.

“…It’s not just a story they hear on TV or videos they watch of testimonials of residential school, but that this is something they also lived,” she says. “So it’s a lot of very mixed feelings around it, and I guess each individual person is conflicted about what it means.”

Shelley Goodleaf has been the principal at Kateri School for five years and worked there for close to 40 years. Goodleaf says she has “done just about every job that needs to be done at the school.”

She was also a student when Kateri was still considered an Indian Day School.

Shelley Goodleaf was a student at Kateri when it was an Indian Day School. Even as a child, she says, teaching had always been her dream. When the building transitioned to an elementary school, she applied for a job. Today, she’s the principal. Video by Luca Caruso-Moro.

“Should I have to write things down or should I just be awarded this just because I went to Day school?” she says. “What do they want? They want actual documentation from everybody. I know I said everybody had their different experiences but we all went to Day School.”

When Canada announced the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement in 2006, it received criticism for being intrusive and re-victimizing those applying for compensation.

Those applying had to provide school records, which could be almost impossible to get depending on the school and age of the individual.

The process for day school compensation is supposed to be different.

“It’s supposed to be less traumatic in this process than through residential schools. I saw the [old] forms and the kinds of questions they asked about abuses and it was horrible,” says Whitebean. “It’s supposed to be a little less intrusive this time but there are still things people will have to share.”

Vernon Goodleaf works on the Health file for the Mohawk Council of Kahnawake, which includes Indian Day School settlement. He’s in charge of overseeing the application process for community members. Video by Luca Caruso-Moro.

If survivors can’t find or access any records, they can still apply by providing a Sworn Declaration and are presumed to be speaking truthfully. They will not be required to provide testimony.

Despite Kahnawakes’s history of Indian Day Schools, Whitebean explains that she focuses on the strength and resilience of the people when writing her Master’s thesis at Concordia University: Child-Targeted Assimilation: An Oral History of Indian Day School Education in Kahnawà:ke.

“To keep loving their kids, to keep trying to overcome it, the way they supported each other,” she says. “So, our legacy and our story is not just one of trauma and abuse and this pain, but that we survived and that we’re rebuilding and reawakening.”

She says, “It’s the good and the bad of where we are today and I hope good comes out of people talking and recognizing things.”

This story relied on archival images from the Kahnawake Cultural Centre and archivist Scott Berwick. Take a look behind the scenes of the archive. Video by Luca Caruso-Moro.