BY Victoria Lewin & Maya Lach-Aidelbaum

Growing plants is second-nature to Jake Pambrum; whether it’s rooted in the classroom where he studies plant biology, or in a closet in his basement surrounded by fluorescent lights. Growing cannabis is Pambrum’s first and only choice of career, ever since he began using the plant to help him go to sleep.

“I started using cannabis, and there were virtually no side effects besides getting the munchies, so it solved a pretty big issue for me, and I feel like if there were more people working on designing strains specifically for medicinal use rather than recreational use, then there could probably be more people helped like I was,” says Pambrum.

However, getting to his goal was going to take some sort of training. Luckily, cannabis education programs have been popping up across Canada since its legalization. One is the Commercial Cannabis program at McGill. According to Pambrum, having a formal education can help budding growers.

Students enrolled in McGill’s commercial cannabis program will be taking courses like plant cultivation in the university’s greenhouses on the Macdonald campus. Photo by Maya Lach-Aidelbaum.

“I think if you’re going to have a job in the industry, then having an education is very important, because if you don’t know what you’re doing with nutrients, you can end up making a product that’s close to what you’d consider poisonous,” says Pambrum.

However, licensed producers (LPs) currently on the hunt for new prospects have a few other reasons to add formal education to their list of requirements.

At first, Great White North Growers’ building looks and feels like any other industrial, factory-like setting; that is until you step through an entrance into the high-security, ultra-sanitized growing operation. The potent smell of a room filled with tall cannabis stalks will overwhelm even the most seasoned cannabis growers’ nostrils. Entering the “mother” room, home to a family of mother plants, is almost enough to induce a foggy buzz.

Blake Falardeau, head grower at Great White North Growers, walks through tall cannabis mother plants in the “mother” room. Photo by Maya Lach-Aidelbaum.

More interesting is the aeroponics room, decorated with massive, spinning modules containing small, hexagon-shaped pockets that each house an individual cannabis plant. This non-traditional method for growing cannabis relies on automatic water and nutrient-dosing, with no need for soil; these roots simply rest in the air inside their individual chambers.

Falardeau explains what it takes to run a high-tech, legal cannabis growhouse. Great White North Growers have a “mother” room and use aeroponic technology to grow cannabis. Video by Maya Lach-Aidelbaum.

Running this high-tech operation at Great White North Growers is Co-Founder and Executive Vice‑President George Goulakos and cultivation manager Blake Falardeau. Goulakos says finding candidates to hire for their growhouse can be challenging at times.

“Most legacy growers are coming from a grey market, working on their own and underground in basements, and now we’re bringing these people into a legal industry that requires paperwork, follow-ups, accountability, and that’s where you don’t always find someone like that in a new industry,” says Goulakos.

In fact, he says that being able to work effectively under the regulations and guidelines of the new cannabis industry is a top requirement for applicants.

“Everyone has to understand, what Health Canada wants to do, is create an industry that has policies, that will take the black market out, that will take pesticides out, that will create a vibrant industry. People have to understand that they have to follow rules and regs, and you have to first understand them,” says Goulakos.

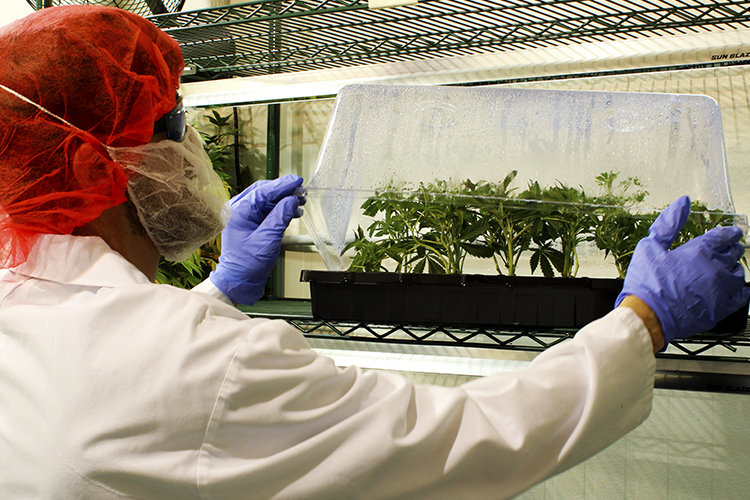

Blake Falardeau checks on young cannabis clones made by cutting off stems from the mother plants. Photo by Maya Lach-Aidelbaum.

Blake Falardeau has been growing cannabis for 20 years, offering consulting services for his friends who were licensed producers. Three years ago, he entered the legal industry in Newfoundland, and arrived in Montreal three months ago after being hired by Great White North Growers. According to Falardeau, agricultural experience isn’t much of a concern when looking for new employees.

“When you’re growing in your basement, there’s no rules, you can do whatever you want,” he says. “When you come into a place like this, everything is recorded, you have to document everything you do, every drop of anything you put anywhere has to be recorded and monitored. Growing the marijuana isn’t the hardest thing about this job.”

While both Goulakos and Falardeau think having a solid foundation of growing knowledge is an essential component to getting hired, Falardeau also feels that the true challenge is finding growers who can handle the strict rules that come with the job.

“It’s more dealing with people, and dealing with the standard operating procedures that we have to follow for Health Canada, that’s the real challenge growing in an LP, the paperwork, following the regulations Health Canada has put in place for us,” says Falardeau.

Blake Falardeau displays the roots of a cannabis plant being grown in their aeroponics room. This non-traditional method for growing cannabis relies on automatic water and nutrient-dosing, with no need for soil. Photo by Victoria Lewin.

Goulakos and Falardeau agree that having an institution that offers formal training for cannabis growing could be the solution to their challenge. Falardeau says that a typical day in the growhouse is highly scheduled. Everyone knows what their given tasks for the day are and what paperwork needs to be filled out. He says having graduates that are able to come in with pre-existing knowledge about these formalities could make onboarding a breeze.

“People can come into the industry already knowing what to expect, and not just thinking they’re going to come in and tell everybody how to grow, you come in and the needs of growing are already established,” Falardeau says.

Goulakos believes the upcoming McGill program could be a key way to bring new growers into the legal market.

“The McGill program is going to help someone that maybe would’ve grown illegally, to give them a career, to formalize their natural gift of growing. Because it’s a gift, like anything else, like a chef, the growers I’ve been exposed to, there’s a relationship with the plant, there’s a pride in the plant, and that’s what you’re looking for,” says Goulakos. “We’re already taking advantage of it, we’ve hired one person from McGill and we’re really happy with him. He came with a really technical mind, a scientific mind, and he’s adding a lot to Great White North.”

Blake Falardeau displays two different types of cannabis plants in the “mother” room. Photo by Victoria Lewin.

Finding candidates who know how to work under Health Canada’s standard operating procedures seems to be a common problem for growers, as Jarred Marsh, an LP consultant at CCS Green, describes challenges faced by many growing operations.

CCS Green, based in Burlington, Ontario, offers cannabis companies a variety of consulting services to help with things like pre-production, regulatory and strategic planning, facilities and operating procedures, as well as hiring and recruitment. According to Marsh, finding candidates to work in the cannabis industry is often about having the right soft skills.

“Often times if you’re in a startup environment, which many of these cannabis companies are, things can change quickly and you need to be able to adapt and be versatile, whether it’s changing regulations, as we’ve seen most recently with cannabis 2.0 products coming out, or just the changing landscape of the industry,” says Marsh.

As aspiring growers move into the legal industry, cannabis cultivators often notice that legacy growers coming from the black market struggle to adapt to regulatory standards.

“Those are things that might need to be taught in a classroom, whether it’s from an operational compliance point of view, or a quality assurance point of view, it’s a new skill set for a lot of these growers that they definitely need to learn, and I think institutional education is a great place for that to happen,” says Marsh.

McGill’s new Commercial Cannabis program was expected to begin welcoming students last year, however the program has yet to go live. It will require students to take courses such as Cannabis Issues and Concerns, focused on legal, regulatory, ethical, health and safety aspects, as well as Commercial Cannabis Production and Contaminants in Cannabis.

McGill’s commercial cannabis program will teach students how to grow cannabis plants in the university greenhouses. Photo by Maya Lach-Aidelbaum.

Acceptance into the diploma program requires a Bachelor of Science in biological, agricultural, or environmental sciences. Pambrum initially thought McGill could be the perfect place for him to pursue his dreams of working in cannabis genetics.

“They go on field trips to grow ops, and you get a three-month internship at a grow op when you do the program, and I think there’s just only so many opportunities to do that in Quebec,” he says.

However the program comes with a hefty price-tag at just over $24,000 for one year and students must attend full-time. This would mean little time for part-time work, leaving Pambrun feeling discouraged.

“The problem is that it’s about $25,000 for one year, which is kind of high especially because you can’t get student loans for it, so you have to pay for that all yourself,” says Pambrum.

Falardeau says the price tag might be worth it, so long as you plan on taking a career in cannabis far enough for it to pay off.

“If you’re training to be a cultivation manager, or a head grower, or a master grower, then that kind of money might be worth it. But if you’re just trying to get your foot in the door, I think $24,000 is a little steep just for an entry-level position,” says Falardeau.

Despite Pambrum’s original passion to attend McGill’s program, another cannabis production program offered at the University of Guelph has caught his attention.

“As a university student who’s paying for himself now, I don’t have the money to pay $25,000 for one year, whereas the Guelph certificate is only about $2,500 for one year, and you can also do it online, which means that you can work while pursuing that certificate,” says Pambrum. “If you do it for McGill, it’s a full time program so it’s hard to work as well.

Cannabis plants are slowly rotating around bright lights in aeroponic towers. The plants do not need soil and their roots simply rest in the air inside individual chambers. Photo by Victoria Lewin.

According to Serge Petitclerc, a spokesperson for Le Collectif pour un Québec sans Pauvreté, McGill is just one of many schools charging a high price for tuition. Specialized programs like the Commercial Cannabis diploma often require that students pay the full amount up front. Petitclerc says tuition is already far too expensive across the board, and specialized programs will only turn students away.

“The moment you put a crazy price tag on educational training, even if by the end of the training there are interesting job opportunities, no one in poverty will want to pay it,” says Petitclerc. “They will ask themselves, ‘What if I don’t pass my classes?’, ‘Do I want to accumulate 24 thousand bucks in debt?’ It’s a huge risk.”

According to Petitclerc, the high cost of such programs prevents low-income individuals from accessing certain types of education, effectively restricting them from entering the industry at all.

“Those who will have access to programs that lead to better salaries are those who already have the best salaries.” says Petitclerc. “Those with less good salaries or who simply don’t have a source of revenue won’t have access to these programs that might be able to improve their living conditions. We are condemning these people to eternal poverty.”

With education being one of the only ways out of poverty for many low-income students, Petitclerc says current tuition costs will only keep this cycle turning.

Comparing cannabis programs across Canada. Media by Victoria Lewin.

According to Statistics Canada, tuition fees across Canada have been increasing steadily each year. In 2012 and 2013, prices jumped by 4.3 per cent and 5 per cent respectively, and have since gone up by 2 to 3 per cent each year. Average annual tuition in the 2018-19 school year was $6,838, a 3.3 per cent increase from the prior academic year.

Additionally, the highest average tuition fees are in the fields of dentistry, medicine, law and pharmacy, coming in at about $15,000, $13,0000, and $11,000 respectively; all of which are a far cry from the fees being charged for McGill’s diploma in Commercial Cannabis.

With the program requiring students to come in with Bachelor’s of Science, total tuition costs for students will come in at just under $38,000 to receive their diploma and enter the cannabis workforce, depending where they’ve completed their Bachelor’s.

“Having expensive specialized programs is even worse than the tuition fees already associated with general university studies,” says Petitclerc “We already think general tuition fees are too high. Now we’re talking about a situation that’s even worse.”

As aspiring cannabis growers look towards educating themselves to make it into the industry, high tuition fees could serve as a barrier not only for students, but for organizations seeking qualified candidates as well.