BY Laurianne Tremblay & Vanessa Ippolito

Catherine Alain is a 22-year-old woman who moved to Montreal just before the pandemic. She says due to remote learning and lockdowns, her experience of moving to the city didn’t go as planned.

“I’m not from Montreal so I counted a lot on school to make new friends and a social network, but the pandemic really just cut all that,” she says. “Since I didn’t have a big circle of friends, every time I had little things happening to me, I felt like I didn’t have the tools to confront [these challenges].”

Catherine Alain working in her apartment. Photo by Laurianne Tremblay.

Alain explains that the measures implemented during the pandemic took a toll on her mental health. It caused her to develop social anxiety, as well as a sense of loneliness and a lack of motivation in her studies.

“I think before I was more of a shy person, but during the pandemic it really turned into social anxiety, since I truly wasn’t used to seeing new people,” she says.

In person learning has been a priority for children. Many teachers and professionals believe it makes a difference in the mental health of students to learn at school.Video by Vanessa Ippolito.

Dr. Amélie Seidah is a clinical psychologist specializing in cognitive-behavioral assessment and the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders. She says the demand for counseling skyrocketed during the pandemic, so much that she couldn’t accept new patients.

“We always had busier periods during the year, sometimes during fall it’s harder, before the holidays, and usually summertime is a lot calmer,” she says. “With the pandemic it didn’t budge, my July has been as busy as my November… I think people are really worn out, so there’s been a lot of demand for consultation.”

At the clinic Argyle, where Seidah works, the waiting time during the pandemic could go as high as six months.

She says she finds it hard having to tell people she cannot put them on her waiting list. As the pandemic progresses, she has difficulty referring them elsewhere since most of her colleagues find themselves in the same situation.

SAQ storefront on Laurier avenue. Photo by Laurianne Tremblay.

Seidah explains how the pandemic has all of the ingredients for stress: a loss of control, unpredictability, novelty and, a threatened ego.

“Collectively we’ve been experiencing those four ingredients […] for almost two years,” she explains. “There is a lot of uncertainty […], some people [are very comfortable with it] but there are others [whom it makes very uncomfortable]”.

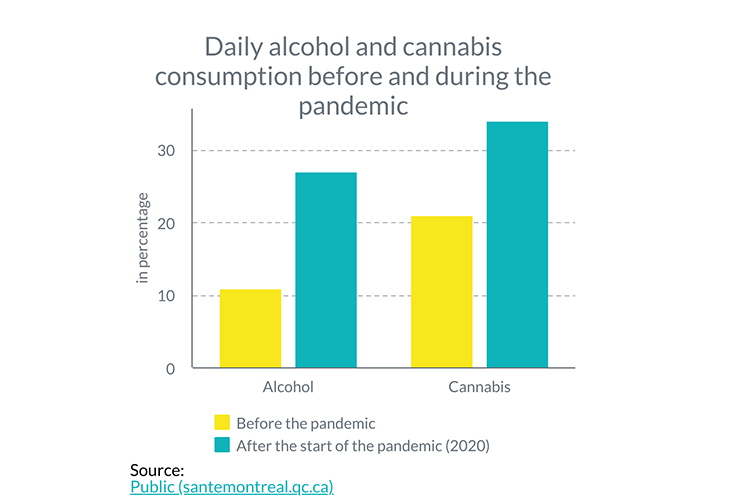

The psychological distress mixed with the difficulty of receiving help caused some people to develop coping mechanisms; some healthy ones like exercising at home, painting, learning an instrument, etc., and some unhealthy ones like increased consumption of alcohol, drugs and tobacco.

“It’s a form of escapism, it’s a way of dealing with stress, or a way of dealing with uncomfortable emotions,” Seidah explains regarding the rise in consumption.

Graphic of the rise of consumption of alcohol, drugs and tobacco in Quebec. Graph by Laurianne Tremblay .

Seidah explains going to a public clinic, a social worker, or a mental health organization is a good option for people to receive help more rapidly. She mentions how not everyone needs to be followed through a process of psychology or psychotherapy; some people might only need someone they can talk to.

Ella Amir is the executive director of AMI-Quebec, a non-profit organization for mental health based in Montreal. She says they saw a change in the nature of psychological distress.

“There is an increase in anxiety around the pandemic, which is reflected in the nature and number of calls we receive,” she says.

Amir continues by explaining how mental health has always been neglected by the government in comparison to physical health.

Mental health has always been inferior in attention to physical health, no question about it. I think that this is reflected in our funding, in research and everything around it.

Since the importance of mental health has been highlighted during the pandemic, Amir hopes that it will continue to be brought up and discussed.

“I certainly hope that you know ultimately mental health is going to be considered [equal to] physical health,” she says.

Empty elementary school hallway. Photo by Laurianne Tremblay.

In January, 2022, Quebec announced an investment of more than $1 billion dollars over five years for mental health. Dr. Seidah hopes it will help with the problem of accessibility.

Catherine Alain explains she saw a shift in-herself when university reopened for in-person learning a year into her studies. Alain says it really helped her to feel motivated again, since she could work with her classmates and this helped her feel less lonely.

“I saw a change when school got back to in-person this fall. I think I’ve never been more social in my life, it seems like I really needed it,” she says. “And then, to be honest, when everything shut down again just before Christmas, that was really rough.”